¶ Stanza 11

This is a short excerpt from Tsong-kha-pa's Three Principal Aspects of the Path. This excerpt expresses the heart of Tsong-kha-pa's understanding of the relationship between emptiness and dependent arising, as elucidated by Nāgārjuna and Chandrakirti. Translations below from Jeffery Hopkins, Paul Hackett, and Adam Percy. While both Hopkins and Hackett's translations keep to the literal truth and grammar of the original, Paul Hackett's translation is purposefully very literal for teaching purposes while Jeffery Hopkins is a little more tuned for English readability.

སྣང་བ་རྟེན་འབྲེལ་བསླུ་བ་མེད་པ་དང་།

སྟོང་པ་ཁས་ལེན་བྲལ་བའི་གོ་བ་གཉིས།

ཇི་སྲིད་སོ་སོར་སྣང་བ་དེ་སྲིད་དུ།

ད་དུང་ཐུབ་པའི་དགོངས་པ་རྟོགས་པ་མེད།

Translation from Jeffery Hopkin's Cutting Through Appearances (pp. 101):

As long as the two, the realization of appearances – the infallibility of dependent-arising –

And the realization of emptiness – the non-assertion [of inherent existence],

Seem to be separate, there is still no realization

Of the thought of Śākyamuni Buddha

Translation from Paul Hackett's Learning Classical Tibetan (pp. 147):

As long as the two – the understanding of appearances [being] the inevitability of dependent arising, and

[The understanding of] emptiness [being] free from assertions [of intrinsic existence] –

Appear separately, for just so long

There will still be no realization of the intention of [Śākya]muni [Buddha] (Hackett)

Translation by Adam Percy (Lotsawa House):

The knowledge that appearances arise unfailingly in dependence,

And the knowledge that they are empty and beyond all assertions—

As long as these two appear to you as separate,

There can be no realization of the Buddha’s wisdom.

Hopkins and Hackett's translations are pretty similar. This is no surprise as Hackett was a student of Hopkins. Percy's is quite different, however, at least the for the first two lines (it seems hard to justify Percy's translation of the first two lines from the grammar). It's interesting to see that all three of them translate ཐུབ་པའི་དགོངས་པ་ differently: “Buddha's wisdom” vs “intention of [Śākya]muni [Buddha]” vs “thought of Śākyamuni Buddha."

¶ Vocabulary

སྣང་བ་ appearances, to appear

རྟེན་འབྲེལ་ dependent arising

བསླུ་བ་མེད་པ་ [deceive-not-exist] infallible, inevitable, without deceiving, incontrovertible

དང་ and

སྟོང་པ་ empty, vacuity

ཁས་ལེན་ [by-mouth-take] assert, accept

བྲལ་བ་ separate, free from, lack, devoid

གོ་བ་ understanding, understand

གཉིས་ two

ཇི་སྲིད་ as long as

སོ་སོར་ individually, individual, separate, distinct

དེ་སྲིད་དུ་ just so long as

ད་དུང་ still

ཐུབ་པ་ muni, Subduer, epithet for Buddha

དགོངས་པ་རྟོགས་པ་ realization of the thought

མེད་ not [exist]

¶ Grammar

We can productively separate these lines into two couplets, so let's start with the first two lines.

སྣང་བ་རྟེན་འབྲེལ་བསླུ་བ་མེད་པ་དང་།

སྟོང་པ་ཁས་ལེན་བྲལ་བའི་གོ་བ་གཉིས།

As long as the two, realization of appearances – the infallibility of dependent-arising –

And the realization of emptiness – the non-assertion [of inherent existence] (Hopkins)

As long as the two – the understanding of appearances [being] the inevitability of dependent arising, and

[The understanding of] emptiness [being] free from assertions [of intrinsic existence] – (Hackett)

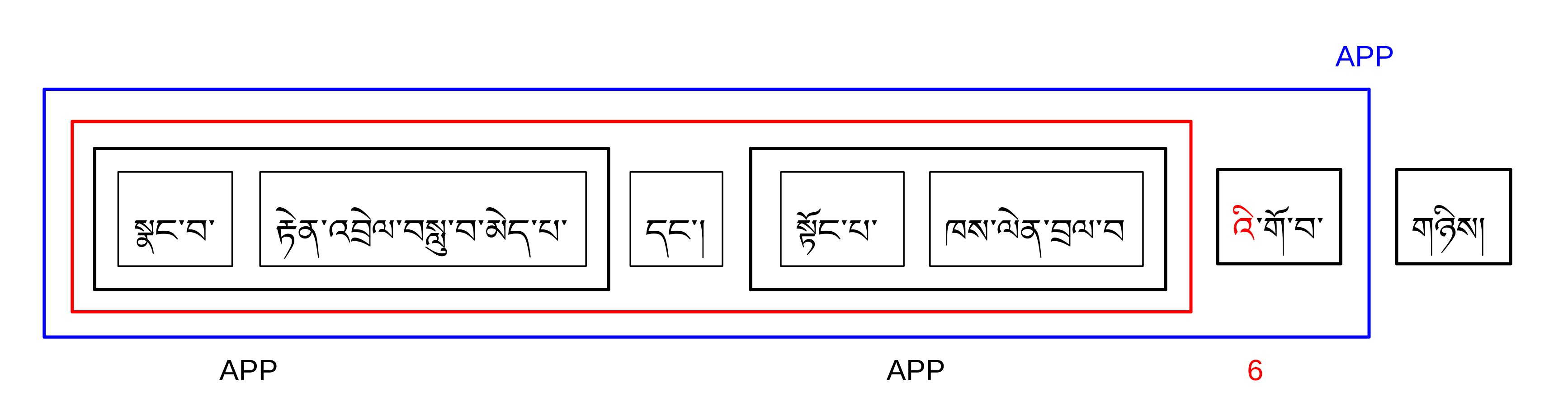

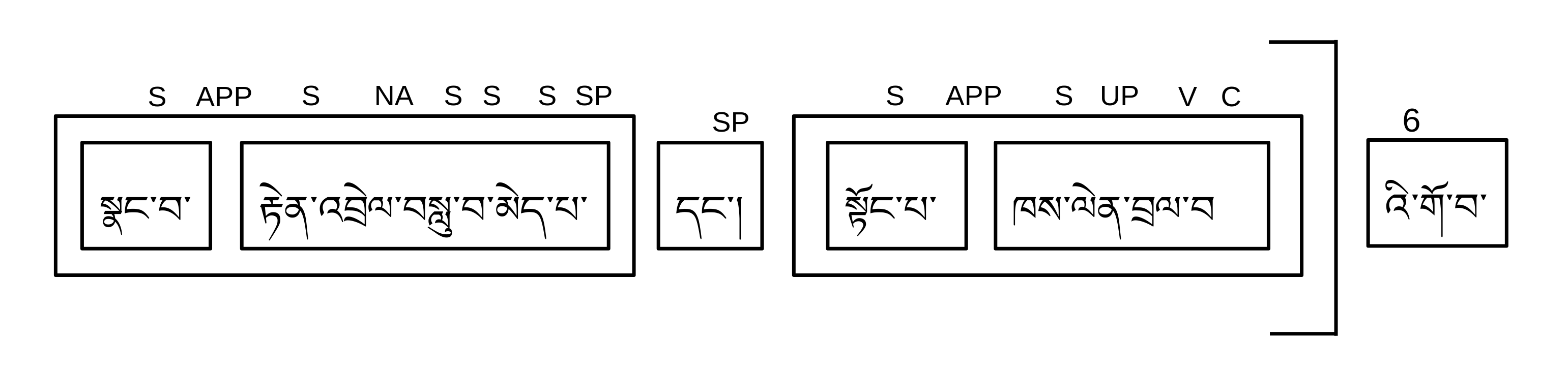

སྣང་བ་ རྟེན་འབྲེལ་ བསླུ་བ་མེད་པ་ དང་།

appearances – dependent arising – inevitability – and

སྟོང་པ་ ཁས་ལེན་བྲལ་བ འི་གོ་བ་ གཉིས།

emptiness – free from the assertion – 6th – understanding – two

The grammar here is not very obvious at first. But it becomes clearer when one realizes that the 6th case at the end of the second line (འི་གོ་བ་) distributes to the entire clause that precedes it, including the first line (སྣང་བ་རྟེན་འབྲེལ་བསླུ་བ་མེད་པ་དང་། སྟོང་པ་ཁས་ལེན་བྲལ་). Further, all of that is in apposition to the two (གཉིས).

Now it's possible to break the structure of the large clause down into two parallel sub-clauses. Both of the sub-clauses have two items in apposition. སྣང་བ་ (appearances) is in apposition to རྟེན་འབྲེལ་བསླུ་བ་མེད་པ་ (inevitability of dependent arising). Likewise, སྟོང་པ་ (emptiness) is in apposition to ཁས་ལེན་བྲལ་བ་ (free from [the] assertion).

སྣང་བ་ [app] རྟེན་འབྲེལ་བསླུ་བ་མེད་པ

appearances – dependent arising – inevitability – [of – understanding]

སྟོང་པ་ [app] ཁས་ལེན་བྲལ་བ འི་[6] གོ་བ་

emptiness – free from the assertion – of – understanding

རྟེན་འབྲེལ་བསླུ་བ་མེད་པ་ is a pretty simple NOUN-ADJECTIVE phrase, taking བསླུ་བ་མེད་པ་ not as a noun and verb clause but as a word itself, meaning inevitable. We have an appositional noun phrase that says appearances, that is to say, the inevitability of dependent arising. Or, as Hopkins writes it, appearances–the inevitability of dependent arising.

I find the phrase the inevitability of dependent arising to be vague. Hackett uses this translation and I've seen it translated this way in other places. What is “inevitable” about dependent arising? I generally think of inevitable in a causative sense. The definition of inevitable is “certain to happen or unavoidable.” “Unavoidable” helps me understand this usage. Dependent arising is unavoidable because all things arise dependently. However, བསླུ་བ་མེད་པ་ literally (taken as a short sentence) means not deceiving or without deceiving. བསླུ་བ་ means controvertible, deceptive, or misleading. མེད་པ་ means not, without, or does not exist. Thus, རྟེན་འབྲེལ་བསླུ་བ་མེད་པ་ means not only that dependent arising is unavoidable but also that it is non-deceptive. The Hopkins translation of infallable seems to more clearly reflect the Tibetna meaning.

But in what sense is dependent arising infallable or non-deceptive? We could say that it is non-deceptive because all things are dependent arisings, all things function exactly because they are dependent arisings, and one who sees this will not be deceived.

ཁས་ལེན་བྲལ་བ་ is a little more complicated in that བྲལ་ is a verb that means free from or lacking and ཁས་ལེན་ can be either a verb that means assert or a noun that means assertion. Here is the noun, assertion. བྲལ་ is a nominative-syntactic verb that typically has the subject in the nominative and thing that is lacking (or which the subject is free from) marked with a དང་.

SUBJECT OBJECT + དང་ བྲལ།

SUBJECT lacks/is free from OBJECT.

Thus the UP dot between ཁས་ལེན་ and བྲལ་བ་, marking where a དང་ has been omitted: ཁས་ལེན་དང་བྲལ་བ་. All of that becomes a verbal noun with the བ་ at the end of བྲལ་བ་, meaning free from the assertion or the non-assertion. The non-assertion of what? We have to fill this in through knowledge and context. The non-assertion of inherent existence. Like before, this is an appositional noun phrase. It says emptiness–the non-assertion of inherent existence.

Putting that together, along with the གཉིས་, we get the following.

the two – the understanding of appearances, the inevitability of dependent arising, and

[the understanding of] emptiness, the non-assertion [of inherent existence]

The parallel construction of these two lines places two pairs of ideas in relation.

- appearances / emptiness

- infallibility of dependent arising / the non-assertion of inherent existence

Understanding the relationship between these two pairs of ideas is central to Tsong-kha-pa's understanding of emptiness and dependent arising. This relationship is made clear in the next two lines.

ཇི་སྲིད་སོ་སོར་སྣང་བ་དེ་སྲིད་དུ།

ད་དུང་ཐུབ་པའི་དགོངས་པ་རྟོགས་པ་མེད།

[As long as … ] Seem to be separate, there is still no realization

Of the thought of Śākyamuni Buddha

¶ What does it mean?

Doctrinally we get to the key point in Tsong-kha-pa's understanding of Nagarjuna's explanation of dependent arising and emptiness. Emptiness is understood as the non-assertion of inherent existence – or, one might say, the (non-implicative) negation of inherent existence. Emptiness is the negation of inhernet existence without imply the existence of anything else. Further, appearances rely on the infallibility of dependent arising. Things (i.e., phenomena) appear because they arise dependently, and if they did not arise dependently, merely imputed by the and on the basis of their parts and on their causes and conditions, they could not possibly appear. Tsong-kha-pa also also closely relates appearances and emptiness (which harkens back to the Heart Sutra, “Form is empty. Emptiness is form."). And, perhaps most interestingly, he equates the infallibility of dependent arising with the non-assertion of inherent existence. All things lack inherent existence because they arise dependently. Because they arise dependently they lack inherent existence. As you can see, there is a lot in these two lines.

You can even, in these few lines, begin to read Tsong-kha-pa's exposition of the two truths as co-equal and mutually interdependent. Conventional truth relies on the ultimate truth, and the ultimate truth cannot exist without the conventional truth. Every emptiness is locked within one entity with a conventional truth and every conventional truth is one entity with its emptiness – there is no other way for them to exist. Yet, at the same time, they are separate. There is no phenomenon that is both a conventional truth and an ultimate truth. Further, in Tsong-kha-pa's presentation, one truth is not “more real” than the other. They are on equal footing. Emptiness is a mere negation, a negation without remainder. All phenomenon, conventional and ultimate, equally lack svabhāva (རང་བཞིན་, inherent existence – or, own-being).

This is in contrast to the various Tibetan traditions and scholars that hold to one of the many flavors of other emptiness (གཞན་སྟོང་), where, in different ways, emptiness is not a non-implicative negation. Emptiness is, in one form or another, a non-compounded union with luminosity or fundamental mind or Buddha nature – a primordial, inherently existent essence. In other emptiness, emptiness is not, itself empty, and the two truths are not equally true.

For comparison, here is a quote from Mipam's Fundamental Mind (translation by Hopkins):

Therefore, although it is called the “sphere of reality,” it is not to be understood as a mere empty sphere but as emptiness endowed with all supreme aspects, without any conjunction with or disjunction from luminosity.

Thus, the meaning indicated by the phrase “basic mind, the clear light, the Great Completeness” is the noumenon of the mind, self-arisen pristine wisdom, this which does not become other than the sphere of reality, primordial basic mode of subsistence, union, the great equality, the great uncompounded due to being immutable and not changing in the three times.

However, there is no way that this could be understood as an impermanent momentary mind, which is a compounded subject, or as a non-thing, an uncompounded mere emptiness that is just an elimination of an object of negation by reasoning.

Therefore, this basal Great Completeness, or primordial basal clear light, great uncompounded union, is the final mode of subsistence of all phenomena, and it also is what is to be realized by the view.

You can see that the presentation of the ultimate truth as presented by Mipam is radically different and consciously opposed to Tsong-kha-pa (and the Gelug) presentation.

While these differences may seem academic, remember that meditation on emptiness is the primary soteriological tool of Tibetan Buddhism, and thus the characteristics of the object one decides to meditate on (potentially for endless lifetimes) has a large amount of importance.

¶ Back to the grammar, looking at the last two lines.

སྣང་བ་རྟེན་འབྲེལ་བསླུ་བ་མེད་པ་དང་།

སྟོང་པ་ཁས་ལེན་བྲལ་བའི་གོ་བ་གཉིས།

ཇི་སྲིད་སོ་སོར་སྣང་བ་དེ་སྲིད་དུ།

ད་དུང་ཐུབ་པའི་དགོངས་པ་རྟོགས་པ་མེད།

Literal(ish) translation:

The realization of appearances, the infallibility of dependent-arising,

and the realization of emptiness, the non-assertion [of inherent existence] – the two –

as long as [they] appear individually,

for that long, still there is no realization of the thought of Śākyamuni Buddha.

Magee / Hopkins translation:

As long as the two, the realization of appearances – the infallibility of dependent-arising –

And the realization of emptiness – the non-assertion [of inherent existence],

Seem to be separate, [for that long],

There is still no realization of the thought of Śākyamuni Buddha

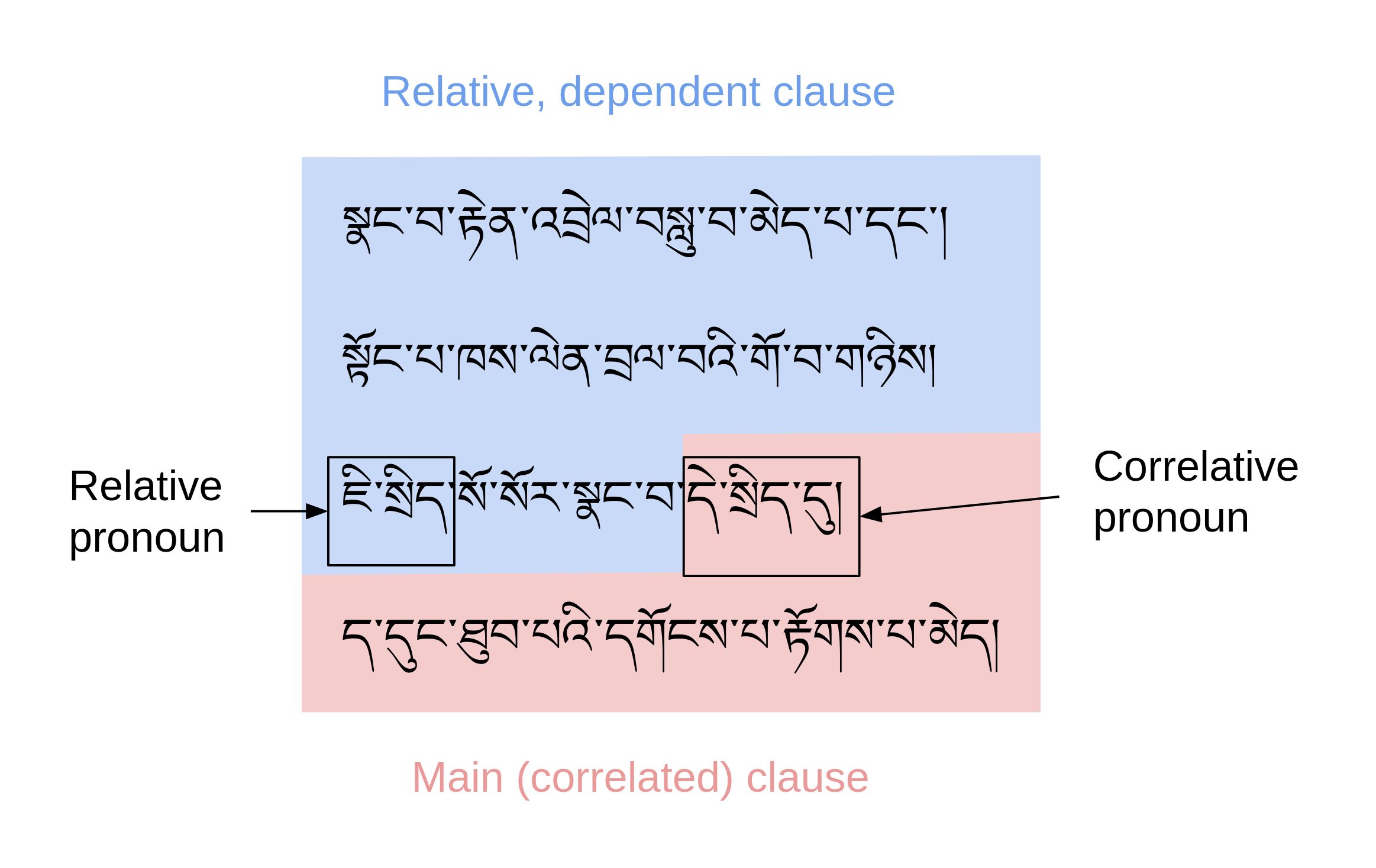

The grammar of the last two lines is relatively simple as compared to the first two lines. The first three lines are a relative, dependent clause that is joined to the last line by a correlative pronoun. Notice how in English to express the relative relationship between the two main clauses (the first three lines and the last line), we only need the conjunction as long as, whereas in Tibetan two pronouns are used: a relative pronoun (ཇི་སྲིད་) and a correlative pronoun (དེ་སྲིད་དུ་).

We can actually simplify the relative clause by removing the first two lines (they standing in for the first two lines):

RELATIVE CLAUSE:

ཇི་སྲིད་སོ་སོར་སྣང་བ་

as long as [they] appear to be separate,

CORRELATIVE CLAUSE:

དེ་སྲིད་དུ།ད་དུང་ཐུབ་པའི་དགོངས་པ་རྟོགས་པ་མེད།

for that long, still there is no realization of the thought of Śākyamuni Buddha.

སོ་སོར་སྣང་བ་ is a short clause that means appear individually. སོ་སོར་ is techincally an adverbially qualifier, thus literally it translates as individually. However, it is a better English translation to say [they] appear [to be] separate. The they in brackets, of course, referring to the first two lines (i.e., appearances and emptiness), which is the subject of the verb སྣང་བ་.

Generally in English, as is the case in both Hopkins and Hackett's translations, the correlative pronoun is untranslated. You can see in my literal(ish) translation, however, I have translated the correlative pronoun (for that long) and it reads as awkward and unnecessary. Also notice the slight difference in word order in Tibetan versus English for the use of ད་དུང་ (still).

With the full text:

RELATIVE CLAUSE:

སྣང་བ་རྟེན་འབྲེལ་བསླུ་བ་མེད་པ་དང་། སྟོང་པ་ཁས་ལེན་བྲལ་བའི་གོ་བ་གཉིས།ཇི་སྲིད་སོ་སོར་སྣང་བ་

The realization of appearances, the infallibility of dependent-arising, and the realization of emptiness, the non-assertion [of inherent existence] – the two – as long as [they] appear to be separate,

CORRELATIVE CLAUSE:

དེ་སྲིད་དུ།ད་དུང་ཐུབ་པའི་དགོངས་པ་རྟོགས་པ་མེད།

for that long, still there is no realization of the thought of Śākyamuni Buddha.

The last line is a simple statement using a verb of existence (or, non-existence in this case) and a verbal noun.

ད་དུང་ཐུབ་པའི་དགོངས་པ་རྟོགས་པ་མེད།

still – subduer – of – thought – realization – not

still there is no realization of the thought of the Subduer (aka, the Buddha)

ཐུབ་ is a verb that means to be able. ཐུབ་པ་ is a word that means ablility or capacity or one who is able. ཐུབ་པ་ is the translation of the Sanskrit word muni, which can be translated as Subduer, and is a epithet for Śākyamuni Buddha. དགོངས་པ་ is thought, intention, or notion. Thus ཐུབ་པའི་དགོངས་པ་ is a simple NOUN-ADJECTIVE phrase: thought of the Buddha. Next there is the verb རྟོགས་ (realize), turned into a verbal noun (realization). Realization of what? Realization of the thought of Śākyamuni Buddha. Notice how this verbal acts as a verb to its left, capturing the preceding noun phrase, but acts as a noun to its right. This is classic verbal behavior. That entire noun (realization of the thought of Śākyamuni Buddha) is then said not to exist using the verb མེད་.

All of this is preceded by ད་དུང་, which is translated as still. The last line reads, then, still there is no realization of the thought of Śākyamuni Buddha. This is the main clause of the sentence. It can stand on its own. The preceding clause (the first three lines), is a dependent clause because they cannot stand on their own (even though they also have a verb and a subject). Notice how as long as [they] appear to be separate does not express a complete thought. It cannot stand on their own because of the relative conjunction as long as.

¶ Stanza 12

ནམ་ཞིག་རེས་འཇོག་མེད་པར་ཅིག་ཅར་དུ། །

རྟེན་འབྲེལ་མི་བསླུར་མཐོང་བ་ཙམ་ཉིད་ནས། །

ངེས་ཤེས་ཡུལ་གྱི་འཛིན་སྟངས་ཀུན་ཞིག་ན། །

དེ་ཚེ་ལྟ་བའི་དཔྱད་པ་རྫོགས་པ་ལགས། །

Translation from Paul Hackett's Learning Classical Tibetan (pp. 147):

At the time when, from just seeing the inevitability of dependent arising [and emptiness]

As simultaneous [and] without alternating,

An ascertaining consciousness thoroughly destroys the mode of apprehension of objects,

Then at that time, the analysis of the view [of emptiness] is complete

William Magee's translation:

When [the two understandings exist] simultaneously without alternation,

And from just seeing dependent-arising to be infallible,

Definite knowledge destroys the mode of apprehending [an inherently existent] object,

Then the analysis of the view is complete.

Translation from Jeffery Hopkin's Cutting Through Appearances (pp. 101):

When [the two realizations exist] simultaneously without alternation

And when, from only seeing dependent-arising as infallible,

Definite knowledge destroys the mode of apprehension [of the conception of inherent existence],

Then the analysis of the view [of emptiness] is complete.

Translation by Adam Percy (Lotsawa House):

Yet when they arise at once, not each in turn but both together,

Then through merely seeing unfailing dependent origination

Certainty is born, and all modes of misapprehension fall apart—

That is when discernment of the view has reached perfection.

¶ Vocabulary

ནམ་ཞིག་ at the time, when

རེས་འཇོག་ alternately, [occasionally-put]

མེད་པར་ without (མེད་ means not or does not exist, with the ར་ you literally might have something like as not existing but really … མེད་པར་ is without …)

ཅིག་ཅར་དུ་ simultaneous; at one time; simultaneously

རྟེན་འབྲེལ་ [depend-connect]; dependent-arising

མི་བསླུ་ [not-deceive]; incontrovertible, infallible, inevitable

མཐོང་བ་ to perceive, to see

ཙམ་ཉིད་ at the moment of, when (this one is potentially confusing because both ཙམ་ and ཉིད་ are also common restrictive particles that mean mere or only).

ནས་ Here is the 5th case particle being used as what Wilson calls a continuative, Craig calls a participle, and Hackett calls a gerund. (ABC ནས་ XYZ = having ABC'd, XYZ )

ངེས་ཤེས་ ascertaining consciousness

ཡུལ་གྱི་འཛིན་སྟངས་ mode of apprehension of object

ཀུན་ all

ཞིག་ destroy, disintegrate, perish (also a common particle used like the singular indefinite article “a” or “an” in English, but here it is the verb destroy)

ན་ when, if

དེ་ཚེ་ at that time

ལྟ་བའི་དཔྱད་པ་ analysis or investigation of the view [view-6th-analysis]

རྫོགས་པ་ complete

ལགས་ is

¶ Grammar

Here it is again, for convenience, with Magee's translation.

ནམ་ཞིག་རེས་འཇོག་མེད་པར་ཅིག་ཅར་དུ། །

རྟེན་འབྲེལ་མི་བསླུར་མཐོང་བ་ཙམ་ཉིད་ནས། །

ངེས་ཤེས་ཡུལ་གྱི་འཛིན་སྟངས་ཀུན་ཞིག་ན། །

དེ་ཚེ་ལྟ་བའི་དཔྱད་པ་རྫོགས་པ་ལགས། །

When [the two understandings exist] simultaneously without alternation,

And from just seeing dependent-arising to be infallible,

Definite knowledge destroys the mode of apprehending [an inherently existent] object,

Then the analysis of the view is complete. (Magee)

The heart of this stanza is the last line. The rest of it is a long dependent clause. ན་ can mean if or when (and also can be a 2nd, 4th, or 7th case particle), but here it means when. At the end of the first three lines, the ན་ ends a long dependent clause that leads into the final main clause. དེ་ཚེ་ means at that time, and the two together operate like a relative-correlative pair (<< todo: is it an actual relative correlative? >>).

… ན། དེ་ཚེ་ལྟ་བའི་དཔྱད་པ་རྫོགས་པ་ལགས། །

When …, at that time the analysis of the view is complete.

The boxed area above is a complete thought expressed by a simple linking verb. ལགས་ is a linking verb, the same as ཡིན་.

ལྟ་བའི་དཔྱད་པ་ རྫོགས་པ་ ལགས

analysis of [the] view – complete – is

This is the relative, dependent clause that is what must happen before the analysis of the view is complete. Gramatically, it can be broken into two sections by the ན་ and the ནས་. The ནས་ plus a verb creates a sense of a dependent sequence. What comes before the ནས་ comes before what follows it (ABC ནས་ XYZ → Having ABC, XYZ).

The VERB + ནས་ construction is confusingly called three different things by Paul Hackett, Joe Wilson, and Craig Preston. Hackett calls it a gerund (based presumably on his strong Sanskrit background). Joe Wilson calls it a continuative, because like དེ་, ཏེ་, and སྟེ་ it creates a sense of sequence. Craig Preston calls it a participle, based on the closest English construction.

ནམ་ཞིག་རེས་འཇོག་མེད་པར་ཅིག་ཅར་དུ། །

at the time – alternating – without – simultaneously

རྟེན་འབྲེལ་མི་བསླུར་མཐོང་བ་ཙམ་ཉིད་ནས། །

dependent arising – [as] infallible – seen – merely – [having]

ངེས་ཤེས་ཡུལ་གྱི་འཛིན་སྟངས་ཀུན་ཞིག་ན། །

definite knowledge – object [of] – mode of apprehension – all – destroys – when

Working backwards, starting with the last line first, ཞིག་ is a verb that means destroy. ཞིག་ is also a particle, much like in English the indefinite article a or an. When used as a particle, it is often untranslated. Here, however, it is the verb.

ངེས་ཤེས་ ཡུལ་གྱི་འཛིན་སྟངས་ཀུན་ ཞིག་

Definite knowledge thoroughly destroys the mode of apprehension of the object.

ངེས་ཤེས་ is the agent, or what is doing the destroying, and ཡུལ་གྱི་འཛིན་སྟངས་ཀུན་, is the object, or what is being destroyed. ཡུལ་གྱི་འཛིན་སྟངས་ is mode or manner of apprehension of the object. Magee does not translate ཀུན་, which literally means all, but you can see in Hackett's translation above it can be translated as thoroughly. The mode of apprehension of the object here refers to apprehending objects as inherently existing.

So for just the last two lines you would have something like:

ངེས་ཤེས་ཡུལ་གྱི་འཛིན་སྟངས་ཀུན་ཞིག་ན། །

དེ་ཚེ་ལྟ་བའི་དཔྱད་པ་རྫོགས་པ་ལགས། །

When definite knowledge thoroughly destroys the mode of apprehension of the object,

at that time the analysis of the view is complete.

However, you need the first two lines for this to make sense.

ནམ་ཞིག་རེས་འཇོག་མེད་པར་ཅིག་ཅར་དུ། །

རྟེན་འབྲེལ་མི་བསླུར་མཐོང་བ་ཙམ་ཉིད་ནས། །

མཐོང་བ་ཙམ་ཉིད་ནས་ is having merely seen or having simply seen or from only seeing. It's a dependent clause that must happen before the next clause happens. What must one see? རྟེན་འབྲེལ་མི་བསླུར་, dependent arising as infallible. The ར་ is a second case complement attached to མི་བསླུ་ (think of the paradigm See all sentient beings as mother). It's not just that you are seeing dependent arising, but that you are seeing it in a particular manner, as infallible. But it's not an adverb. You're not infallibly seeing dependent arising. You're seeing dependent arising as infallible.

If you look at Paul Hackett's translation (the inevitability of dependent arising), he translates this more as a complement that informs us more about dependent arising than how we're supposed to see it. I have a hard time seeing Hackett's translation here in the text, particularly since his stated aim with this translation was to be very literal. Magee and Hopkin's translations are much closer to the reading I see in the text.

The first line is interesting.

ནམ་ཞིག་རེས་འཇོག་མེད་པར་ཅིག་ཅར་དུ། །

at the time – alternating – without – simultaneously

As simultaneous [and] without alternating, (Hackett)

When [the two understandings exist] simultaneously without alternation (Magee)

When [the two realizations exist] simultaneously without alternation (Hopkins)

Hackett seems to read this line as a second case complement: seeing dependent arising and emptiness as simultaneous and without alternating, rather than interpreting it as an adverb, which is my first impulse. Interpreted as an adverb, instead of seeing them as simultaneous and without alternating, we see them simultaneously and without alternating. They both modify the action of seeing in a way, but the former tells us how we see the object and the latter is more specificlaly about the action of seeing itself. It makes more sense to me as an adverb because it is the action of seeing that can alternate, not the mode of existence of the two realizations, which are always necessarily simultaneous.

Magee and Hopkins, who both translate the line essentially the same, bracket in an unstated clause ([the two understandings exist]) to make it a separate part of the when condition.

Except for the introductory ནམ་ཞིག་, which means at the time when, the first line is an adverbial clause that modifies མཐོང་བ་. It tells us how we should see (depedent arising as infallible).

ནམ་ཞིག་རེས་འཇོག་མེད་པར་ཅིག་ཅར་དུ། །

at the time – alternating – without – simultaneously