¶ Doctrinal Vocabulary and Grammar – Cyclic Existence

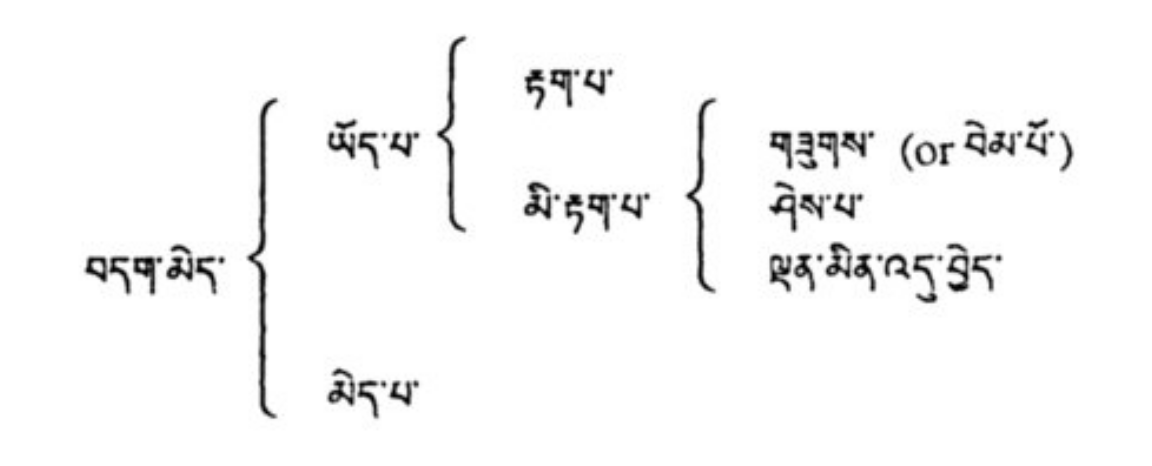

In chapter 9 you were introduced to the main divisions of the selfless. Below is a summary of what you've seen so far. Remember that because all phenomena lack inherent existence, selfless (བདག་མེད་) is the primary category, not existent and non-existent, which are subdivisions of selfless.

བདག་མེད་ selfless

- ཡོད་པ་ existent

- རྟག་པ་ permanent

- མི་རྟག་པ་ impermanent

- གཟུགས་ or བེམ་པོ་ form or matter

- ཤེས་པ་ consciousness

- ལྡན་མིན་འདུ་བྱེད་ non-associated compositional factors

- མེད་པ་ non-existent

Chart from Wilson:

Notice the implicit heirarchy of division here:

- lack of inherent existence

- existence vs non-existence

- permanent vs impermanent

- mind, matter, and other (compositional factors)

Permanent, of course, as used here, does not mean eternal but static, and impermanent does not simply mean temporary but changing moment by moment. The key point is that impermanent phenomena are functioning things that perform the function, primarily, of creating their next moment. Permanent phenomena, in contrast, are non-functioning and do not create their next moment. So long as they abide, they remain unchanging. But once the causes and conditions that brought them about change or cease, the permanent phenomena ceases as well. Both permanent phenomena and impermanent phenomena are necessarily existent phenomena that are merely imputed by the mind on the basis of their parts and their causes and conditions.

Why care about all these divisions of phenomena? What does it matter? Don't we just want to sit and clear our minds and wait for enlightenment to strike?

There are certainly Buddhist belief systems that say as much. However, what I (Andrew) have found is that the afflicted mind is very tricky. It is slippery. I found that when I examined how I was using words and concepts, I realized that what I took to be concrete, specific signifiers of meanings (words) actually represented vague clouds of connections and connotations. Even important words like mind, love, truth, etc… I really had only a vague idea of what I meant when I said them.

This vagueness creates a lot of space for doubt, misunderstanding, denial, and spiritual bypassing. I found that I could pretend to have an understanding of something without actually understanding it (much less realizing it), and worse, this space left me open to manipulations based on ignorance, craving and anger. The mind, as I said, is tricky, and if you let it wiggle around, wiggle it will, and soon you'll be back at the bars at closing time spouting metaphysics, talking about it “all being one” and how we should all just relax while quoting Fritjof Capra to retired postal workers who just want to drink away their regrets in silence while watching TV. This of course, despite the large number of people that engage in such behavior, will never lead to deep realizations.

One of the beautiful things I've found about the Tibetan Buddhist system, and the Gelug system in particular, is that through an extensive systematization and a strict technical vocabulary, it nails our thoughts and ideas down to specifics so that we begin to have a basis with which to work. We have to nail reality down, otherwise our minds will jerk us around like a street hustler playing three-card monte. But once we nail reality down, we can use terms and concepts to begin to slowly peel away the layers of illusion and samsara until finally, in the end, we discover that we have used concepts to reach the end of concepts and we arrive at a direct realization.

Another way to think about it is this. Imagine you are lost in a cave. You could wander around in the cave endlessly and given enough time, you might find your way out. Or you could talk to some people. Imagine you run into someone that says, “Oh, yeah, the exit? It's over that way,” and they point in a general direction. Well, that's somewhat helpful, but when you try and follow their directions, you quickly get lost again. Next, imagine you run into someone that hands you a detailed map that shows you exactly where you are in the cave. This time you follow the map and confidently march out of the cave into the warm sunshine and trees beyond. At that point, the map falls from your hands, unneeded. The map, in the end, has nothing to do with the sunshine and the trees – yet, without it, you would likely never have found your way to them.

All of these terms and definitions, all of these hierarchies and taxonomies, they are simply the map out of the cave of samsara. Eventually, they can and will be abandoned, but if you want to find your way out of the cave, don't abandon them too soon (in fact, probably shouldn't abandon them until you feel the warmth of the sunshine on your face), and you probably ought to study them pretty carefully for a while until you figure out where you're going.

The sort of taxonomy presented above is at the heart of the Tibetan Buddhist examination of the universe. I will return to the discussion of impermanent phenomena, their divisions, and the definitions of these categories later. For now, the focus will be not on a philosophical analysis of phenomena according to whether they are permanent or impermanent, or whether they are physical or mental, but in terms of the value given them in the practice of Buddhism. In this chapter and the next you will be introduced to the basic terminology used to discuss cyclic existence and nirvana.

The Buddhist cosmos – viewed cosmologically or psychologically (the two are hard to separate in Buddhism) – consists of cyclic existence (འཁོར་བ་, saṃsāra) and nirvana (མྱ་ངན་ལས་འདས་པ་, nirvāṇa). Together they are abbreviated འཁོར་འདས་, which literally means cycling/turning [and] transcended.

འཁོར་བ་ is a verbal noun constructed from the verb འཁོར་ (which means turn), as is the noun འཁོར་ལོ་ (cakra), meaning wheel. འཁོར་ is a nominative verb that has no objects, just a subject that is not marked by a case marking particle. This is seen in the example sentence འཁོར་ལོ་འཁོར། (The wheel turns).

འཁོར་བ་ thus refers to the involuntary cycling of the individual from one form of sentient life to another that characterizes the Buddhist cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. མྱ་ངན་ལས་འདས་པ་ literally means transcended suffering.

མྱ་ངན་ suffering, pain

ལས་ from, beyond

འདས་པ་ passed, transcended

Suffering here refers to the first of the four truths (see chapter 13), where cyclic existence is equated with suffering (སྡུག་བསྔལ་), or sometimes more broadly, as unsatisfactoriness.

འཁོར་ལོ་ wheel

འཁོར་ (v) turn

མྱ་ངན་ལས་འདས་པ་ [sorrow-from-passed] nirvāṇa

འཁོར་འདས་ (abbr.) saṃsāra and nirvāṇa

ཁམས་ realm

སྡུག་བསྔལ་ suffering

སྡུག་བསྔལ་ – Suffering and pain or unsatisfactoriness?

སྡུག་བསྔལ་ is the Sanskrit word duḥkha. Generally this is translated as suffering. Some teachers like to talk about duḥkha as unsatisfactoriness (this seems particularly true in the westernized, less “religious” forms of Buddhism). I asked Bill Magee about this in class at Maitripa. He said the buddha did not sit under the bodhi tree for a week and teach 84,000 sutras because he was vaguely dissatisfied with life. The Buddhas and the Bodhisattva's strive endlessly because life is suffering, life is painful and ends in sickness and parting with everything and everyone we know. Life hurts. We never get what we want. We want what we do not have. Then we die, often in horribly painful ways.

Some of this confusion comes from the lack of subtlety in the English words for suffering. Just like the probably false story that the indigenous people of the far north have many words for snow, the Tibetans have different types and divisions of suffering. There are common groupings of the 3, 6, and 8 types of sufferings. Unsatisfactorines is one type of suffering, as is good old garden-variety pain and suffering. Surprisingly, even pleasure is a type of suffering. Pleasure is said to be like scratching an itch or drinking salt water: it satisfies for a moment but in that moment creates further need and dissatisfaction.

Thus when texts use the word སྡུག་བསྔལ་ they mean all of these meanings.

It's important to remember that when Buddhist delineate all of this suffering, it is always in the context of the path out of suffering. It's not just that we suffer, but that we suffer needlessly and there is a way not to suffer. We suffer because we misunderstand reality, and because of this misunderstanding, have created the conditions for our own suffering.

In essence, they're not saying “Life is miserable. Good luck.” They're saying “Feel that? That hurts, doesn't it? Maybe you should try not hitting yourself.”

The three types of suffering (སྡུག་བསྔལ་གསུམ་, triduḥkhatā)

- suffering of suffering (སྡུག་བསྔལ་གྱི་སྡུག་བསྔལ་, duḥkha duḥkhatā) – what we normally think of as suffering

- suffering of change (གྱུར་བའི་སྡུག་བསྔལ་, vipariṇāma duḥkhatā) – what we normally think of as pleasure

- all-pervasive suffering of conditioning (ཁྱབ་པ་འདུ་བྱེད་ཀྱི་སྡུག་བསྔལ་, saṃskāra duḥkhatā) – that every aspect of our lives has been created from causes and conditions pervaded with the afflictions (ignorance, craving, and anger) such that every aspect of our lives are [phenomena that are] sufferings

Read the Rigpa Wiki article on the Three Types of Suffering.

The Six Types of Suffering (from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive):

- nothing is definite in samsara,

- nothing gives satisfaction in samsara,

- we have to leave this samsaric body again and again,

- we have to take rebirth again and again,

- we forever travel between higher and lower in samsara,

- we experience pain and death alone.

The Eight Types of Suffering (also known as the sufferings of humans):

- the suffering of birth,

- old age,

- illness,

- death,

- encountering what is unpleasant,

- separation from what is pleasant,

- not getting what you want, and

- the five appropriated aggregates.

There are, in cyclic existence, three main regions. Cosmologically, these three are generic categories of rebirth. Psychologically, they are levels of mental functions – ranged not from least to most valuable, but from those bound in desire and hatred to those absorbed in trance. All three, from the Buddhist perspective, are flawed.

འཁོར་བ་ saṃsāra, cyclic existence

- འདོད་པའི་ཁམས་ / འདོད་ཁམས་ desire realm, kāma-dhātu

- གཟུགས་ཀྱི་ཁམས་ / གཟུགས་ཁམས་ form realm, rūpa-dhātu

- གཟུགས་མེད་པའེ་ཁམས་ / གཟུགས་མེད་ཁམས་ formless realm, arūpya-dhātu

In the names of the realm, they are frequently abbreviated by omitting the middle syllable. འདོད་པའི་ཁམས་ becomes འདོད་ཁམས་, for example.

On the three realms and their subdivisions, see Lati Rinbochay et al, Meditative States in Tibetan Buddhism, pp. 23-47

ཁམས་ (dhātu) and has various meanings. It is the name of a place in Eastern Tibetan, Kham. It can also mean constituent, basic constituent, realm, element, disposition, type, and constitution [as in health]. The most common usages are as seen above to mean realm and to mean constituent or element. When ཁམས་ is taken to mean realm, it is divided into the three realms (as seen above). Another common division is into the 18 sensory elements consisting of the six objects, the six sense powers, and the six consciousnesses (see the Rigpa Wiki entry on the 18 dhatus).

The desire realm includes humans and gods (female and male), while only various types of goddesses and gods live in the form and formless realms.

We can break down the grammar of གཟུགས་མེད་པའེ་ཁམས་ in the following manner.

1) Begin with the phrase གཟུགས་མེད་ (forms-not or forms do not exist)

2) Make the verb མེད་ into a verbal མེད་པ་ (adding a generic nominalizing syllable). གཟུགས་མེད་པ་ means [somewhere] forms do not exist or [something or someone] without form.

3) Add the 6th case connective particle འི་ (which connects nouns, pronouns, and adjectives with other nouns). In this case it connects གཟུགས་མེད་པ་ with ཁམས་, connecting [something or someone] without form to realm. ཀྱི་ in གཟུགས་ཀྱི་ཁམས་ is also a 6th case connective particle.

4) With the addition of ཁམས, the root word in the noun phrase, we get the final product: realm that lacks form or formless realm. Here we are taking the 6th case as a type connective. What type of realm? The type without form.

Although only gods and goddesses are born in the form and formless realms, one finds all six principal types of rebirths in the desire realm, not just humans and gods. The six types of rebirth are the following – listed from the most unpleasant to the most pleasant.

འགྲོ་བ་ migrators or go-er's

- དམྱལ་བ་པ་ hell beings

- ཡི་དྭགས་ hungry ghosts

- དུད་འགྲོ་ animals

- མི་ humans

- ལྷ་མ་ཡིན་ demigods

- ལྷ་ gods

The word for hell is དམྱལ་བ་, thus a hell being is དམྱལ་བ་པ་ (hell plus a nominalizing suffix). This may seem a little strange because དམྱལ་བ་ already has a generic nominalizing suffix, but the addition of the second normalizing suffix turns the noun hell into someone or something related to hell, in this case hell-being – a person born in one of the various Buddhist hells. Note, however, that demigod, or ལྷ་མ་ཡིན་, which means not god, lacks any kind of nominalizing suffix but is still a being.

Tibetan does not often speak of the six types of rebirths as rebirths. They are sometimes referred to as births (སྐྱེ་བ་), but more often the term འགྲོ་བ་ is used. འགྲོ་བ་ is a verbal noun built from འགྲོ་ (to go) and literally means go-er, or, in this case, migrator.

Everyone from gods to hell beings is such a go-er, or འགྲོ་བ་, because they migrate through cyclic existence endlessly. In Tibetan Buddhism, neither hells nor heavens are eternal. Beings born there eventually die and travel on to another existence.

སྐྱེ་བ་ births

འགྲོ་བ་ migrations, migrators, goers

སེམས་ཅན་ sentient being (means animal in colloquial, but in classical means all sentient beings)

གང་ཟག་ person

Everyone in cyclic existence is also known as a sentient being or སེམས་ཅན་ (sattva) and a person or གང་ཟག་ (pudgala). When used in texts, གང་ཟག་ is often used with the negative connotation of a person full of afflictions and suffering stuck in samsara while སེམས་ཅན་ is used with a more neutral connotation. Both སེམས་ཅན་ and གང་ཟག་ include all sentient beings, people as well as animals.

Colloquially, སེམས་ཅན་ is used to mean animals only, not including people.

There are a number of subdivisions within these six types of rebirths. Texts on the stages of the path to enlightenment – a genre of literature called Lam-rim (ལམ་རིམ་) from ལམ་ path and རིམ་ stage – speaks of many types of hells, including eight hot hells and eight cold hells. There are also various types of hungry ghosts and many different levels of gods. Although these need not concern us at this point, it will be useful to be aware of some of the Tibetan names of animals since these occur in all varieties of Tibetan literature.

Name of animals in Tibetan:

རྟ་ horse

བྱ་ bird

བ་གླང་ ox

ཕག་པ་ pig

གླང་པོ་ཆེ་ elephant

སྟག་ tiger

སྦྲུལ་ snake

ཉ་ fish

ཁྱི་ dog

སེང་གེ་ lion

Buddhist cosmology holds that these animals, as well as the other five types of sentient beings, inhabit a world-system (འཇིག་རྟེན་, loka) centered on a mountain called Meru or Sumeru in Sanskrit and in Tibetan རི་རབ་ལྷུན་པོ་, which is often abbreiated རི་རབ་ and referred to metaphorically as རིའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་, king of mountains.

The connective particles, such as འི་ from རིའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་, are some of the most commonly used syntactic particles. See chapter 12 for a detailed look at the sixth-case connective. There are five connective particles: གི་ ཀྱི་ གྱི་ འི་ ཡི་.

Notice that in རིའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ the འི་ does not follow the word it connects (རི་) but actually joins with it. This is pronounced a bit like “ree” in English, like the “ee” from "reef" but enlongated. Recall that according to exception seven of the pronunciation rules,

- པའི་ is pronounced (high tone) bë,

- པོའི་ is pronounced (high tone) bö,

- དེའི་ is pronounced téí,

- སུའི་ is pronounced (high tone) sü, and

- རིའི་ ríí.

Very often Tibetan texts speak of the part of the universe where we live as འཛམ་བུའི་གླིང་ or as the southern continent. The reference is to the four continents of this world system, where འཛམ་བུའི་གླིང་ (Jāmbudvīpa) is the continent south of Mount Meru.

འཛམ་བུའི་གླིང་ Jambu Continent

གླིང་ island, continent

The various realms and levels of cyclic existence – in terms of the people who experience them – are discussed in more detail in Perdue, Debate in Tibetan Buddhism, pp. 367-373.

Cyclic existence is treated psychologically as well as cosmologically in Tibetan texts. From that perspective, cyclic existence is a result of action (ལས་, karma) and afflictions (ཉོན་མོངས་, kleśa). Action here means not just any action, but that done by humans and other sentient beings, and then (as a cause of cyclic existence) only when it is intended and when it is motivated by attachment, aversion, or ignornace.

ཉོན་མོངས་ afflictions, kleśa

དུག་གསུམ་ three poisons

- འདོད་ཆགས་ attachment or desire

- ཞེ་སྡང་ aversion or hatred

- གཏི་མུག་ obscuration, same as མ་རིག་པ་, ignorance

These are the three main negative attitudes in Buddhist psychology. They are also known as the three poisons, or དུག་གསུམ་.

Just as the phrase meaning cyclic existence and nirvana may be abbreviated as འཁོར་འདས་, so the causes of cyclic existence, ལས་དང་ཉོན་མོངས་ (karma and afflictions), can be abbreviated ལས་ཉོན་. Not just any action leads to cyclic existence, only ones that are contaminated (ཟག་བཅས་) by being motivated by afflictions such as attachment, aversion, and ignorance.

ལས་དང་ཉོན་མོངས་ karma and afflictions, the causes of cyclic existence

ལས་ཉོན་ abbr. or ལས་དང་ཉོན་མོངས་

ཟག་བཅས་ contaminated, tainted

ལས་ that has been ཟག་བཅས་ by being motivated by one of the དུག་གསུམ་ is the cause of འཁོར་བ་

See Geshe Rabten, Treasury of Dharma, pp. 36-38, 53-60.

¶ Vocabulary (pp. 180)

¶ Nouns

འཁོར་འདས་ cyclic existence and nirvana

འཁོར་བ་ cyclic existence

གླང་པོ་ཆེ་ elephant

གླིང་ island, continent

རྒྱལ་པོ་ king

རྒྱལ་བ་ conqueror

རྒྱལ་མོ་ queen

འཇིག་པ་ disintegration

ཉ་ fish

གཏི་མུག་ obscuration

ཐེག་པ་ཆེན་པོ་ great vehicle [Mahāyāna]

ཐེག་པ་ vehicle

རྟོག་མེད་ non-conceptual

སྟག་ tiger

དུག་ poison

དུད་འགྲོ་ animal

འདོད་ཁམས་ desire realm

འདོད་ཆགས་ desire, attachment

ཕག་པ་ pig

ཕྲ་མོ་ subtle

བ་གླང་ ox

བྱ་ bird

སྦྲུལ་ snake

མ་འོངས་པ་ future

དམིགས་པ་ observation, object of observation

དམྱལ་བ་ hell

ཚིག་ word

ཙིག་ཕྲད་ particle

འཛམ་བུའི་གླིང་ Jambu Continent

ཟག་པ་ contamination

ཟག་བཅས་ contaminated

ཟབ་མོ་ profound

གསུགས་ཁམས་ form realm

གསུགས་མེད་ཁམས་ formless realm

ཞེ་སྡང་ hatred

ཡི་དྭགས་ hungry ghost, preta

ཡུལ་ object, place

ཡུལ་ཅན་ subject

རིམ་པ་ stage

སེང་གི་ lion

སྲུང་མ་ guardian

ལྷ་མ་ཡིན་ demigod, asura

¶ Verbs

སྐྱེ་ is born, arise – III

འཇིག་ destroy, dissolve, do away with, smash – V

འཇིག་ disintegrate, rot, crumble away – III

འདའ་ pass [beyond], transcend – IV p227

འདས་ past form of འདའ་

འདོད་ wish, assert, claim [that] – V p238

མིན་ is not – I/linking

མེད་ does not exist – II, Verb of existence

དམིགས་ observe, take as an object – VI p348

འོང་ come, arrive, come about – III p408

འོངས་ past of འོང་

རིག་ know – III p419

¶ Adjectives

དགེ་བ་ virtuous, wholesome

ཆེན་པོ་ large, great

འཇིག་པ་ disintegrating

ཐ་དད་ different

ཐ་མི་དད་ non-different, not different

མི་དགེ་བ་ non-virtuous, unwholesome

མི་འཇིག་པ་ non-disintegrating

¶ Syntactic Particles

གཞན་ཡང་ moreover

ཡང་ན་ alternatively