¶ Chapter 11

¶ Intro and Review

In the last chapter, a technique for analyzing sentence structure was introduced, that of identifying the functions played by the dots that end every Tibetan syllable, particle, word, clause, and sentence.

The functions of the dots are actually the ways in which particles, words, and phrases relate, as units, to the words around them (not to any actual “function” of the dots).

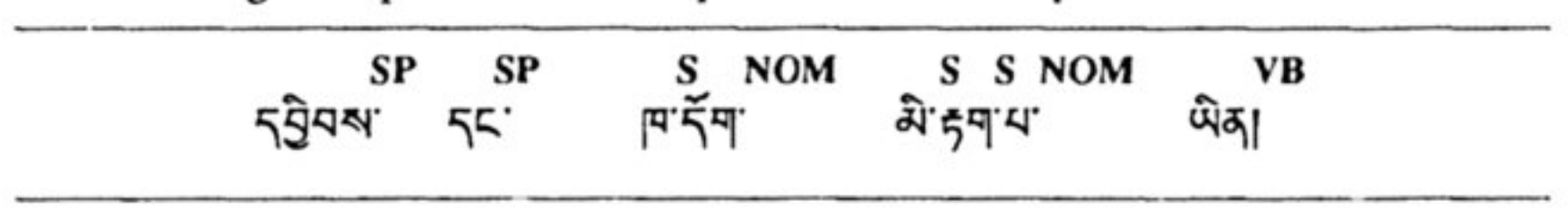

The principal of Tibetan grammar underlying this method of analysis cannot be repeated too often: a noun or pronoun should be considered a unit that connects with or leads to what comes after it and not what comes before it. Only at the end of its last syllable does a noun or pronoun relate to the phrase, clause, or sentence in which it occurs. This relationship, with a few regular exceptions, is one that moves to the right, toward the end of the sentence.

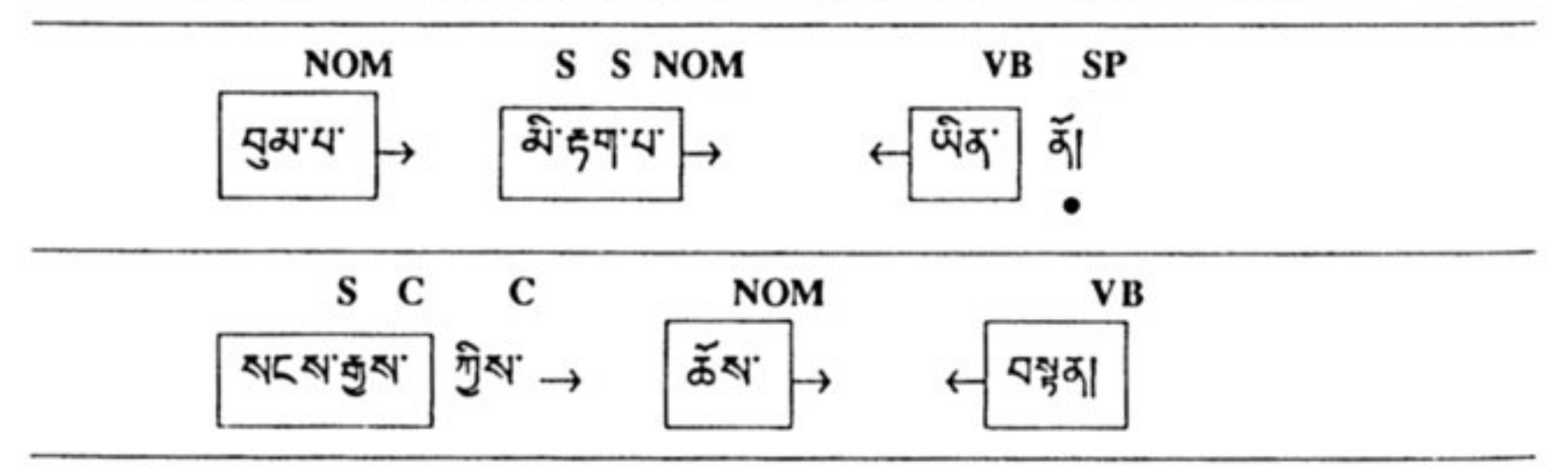

This principal holds true for entire clauses as well. Only at their end are they connected to the sentences in which they occur. A verb, however, is part of a sentence that relates (as a verb) only to the nouns and adverbs that precede it – words that are to its left. These principals of Tibetan syntax are diagrammed as follows.

NOUN or PRONOUN → ADVERB → ← VERB

Tibetan clauses and sentences all have a subject. Most have an object or a complement – these are all nouns, pronouns, or noun phrases. The way in which adjectives work will be discussed later in this chapter.

¶ Phrases, Clauses, and Sentences

Words, syntactic particles, and case marking particles are the building blocks for the construction of phrases, clauses, and sentences.

In terms of the hierarchy of structure:

SENTENCE > CLAUSE > PHRASE > WORD > SYNTACTIC PARTICLE

Sentences are the most complex of these units, often incorporating within themselves phrases and clauses. Sentences have subjects and objects, and they end in verbs.

Sentence

- phrases

- clauses

- subjects and objects, also may have qualifiers and complements

- end in terminal verbs

Clauses may be thought of as sentences modified so that they may be used as components of other, larger sentences. Clauses often end in verbals instead of a terminal verb.

Clause

- part of a sentence

- phrases

- can have subject, object, qualifier, complement, etc…

- end in verbal (instead of terminal verb)

Phrases are groups of words and particles that are more complex than simple words by themselves but not complex enough to be considered a clause. Phrases are merely lists of nouns or nouns modified by adjectives (called noun phrases).

Phrase

- list of nouns and adjectives

- no verb (except possibly verbal nouns)

¶ Sentences

Craig Preston does a really great job of introducing the basic structure of Tibetan sentences in his book How to Read Classical Tibetan, Vol 2, pp. 37-47.

Sentences are constructed minimally of a subject and a predicate, where the predicate includes its closing verb, phrases qualifying that verb, and its object or complement.

Tibetan is more lenient than English in terms of what must be explicitly stated. Frequently either the subject or the object will be omitted. Agents ("subjects" of transitive verbs) are very often omitted, particularly when the agent is the Buddha or when the agent is a general “someone" or “one" or if the agent is easily understood from context.

Wilson and Preston have a different system of names for some of these words. Preston uses subject for intransitive verbs and agent for agentive verbs. Wilson mostly uses subject for both.

The subject of a verb or verbal is, in most instances, it’s agent, the thing or person that performs the action indicated by the verb (or exists). It is frequently unstated. In the case of existential verbs, the subject is the thing or person that is something, that exists, and so on.

¶ Agentive subject (or agent)

སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་ཆོས་བསྟན།

The Buddha taught the doctrine.

¶ Subject of an existential verb

རི་ཡོད།

Mountains exist.

¶ Subject of a linking verb

སྒྲ་མི་རྟག་པ་ཡིན་ནོ།

Sound is impermanent.

Whereas action verbs have objects – the doctrine that Buddha taught – linking verbs have complements, for example, impermanence in Sound is impermanent. Action verbs can also have complements, however, that tell the reader more about the object. The difference is that with linking verbs, the complement is required. In fact, it's possible to omit the subject of a linking verb but one cannot ever omit the complement of a linking verb. Thus, if you find a linking verb with only one phrase or clause in the nominative, it must be the complement.

The predicate of a sentence includes its closing verb, phrases qualifying that verb, and its object or complement. We also (perhaps more frequently) speak of predicates in the context of syllogisms and consequences. Here we are talking about grammatical predicates, which is a slightly different and more general usage than when talking about Tibetan logic.

¶ Predicate of action verb

སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་ཆོས་བསྟན།

The Buddha taught the doctrine.

¶ Predicate of a linking verb

སྒྲ་མི་རྟག་པ་ཡིན་ནོ།

Sound is impermanent.

Most sentences are composed not merely of words, but also of case marking particles and syntactic particles. Sentences may also incorporate phrases and clauses.

A Tibetan sentence is a meaningful group of words that ends in a verb, but is not part of a larger sentence of clause. Sentences may end in:

- basic verb forms, such as ཤེས་

- basic verb + terminating syntactic particle, such as ཤེས་སོ་

- a compound verb, such as ཤེས་ནུས་ (able to know)

- or a verb phrase, such as ཤེས་པར་བྱ་

Much of the game translating Tibetan begins by scanning a piece of text looking for terminal verbs. Tibetan sentences are frequently more like paragraphs in English and in translation may be broken into multiple sentences. It is important to begin to recognize the typical patterns that end sentences as this will allow you to box off sections of grammar to begin to build possible maps of the structure of the sentence.

Terminating syntactic particles are your friend. They definitively end a sentence and stop the grammar. They are about as close to actual punctuation as one gets in Tibetan. Remember that the ། mark does not necessarily end a sentence even if they are sometimes used to end sentences.

The pattern of words and particles seen in a sentence can be thought of as being determined by the type of verb that ends the sentence. This is exemplified in the following two sentences, the first of which ends in a nominative verb and the second in an agentive verb.

¶ nominative-nominative

བུམ་པ་མི་རྟག་པ་ཡིན་ནོ།

Pots are impermanent.

ཡིན་ is a linking verb, that is, a nominative-nominative verb – one whose subject and complement are both in the nominative case (no case marking particle). Thus, the subject (བུམ་པ་) is a simple noun with no case marking particle following it and the complement (མི་རྟག་པ་) also lacks a case marking particle.

¶ agentive-nominative

སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་ཆོས་བསྟན།

The Buddha taught the doctrine.

In the second example, the verb སྟོན་ – seen in the past tense form བསྟན་ – is an agentive-nominative verb. The subject (སངས་རྒྱས་) is marked by an agentive case particle. The object (ཆོས་) is a simple noun in the nominative case.

I say “can be thought of as being determined by the type of verb that ends the sentence” above because while the Wilson system teaches that the verb determines the grammar of the sentence, I find it helpful to think a little more holistically. I think it is the interaction between the verbs and the case markings used that determines the grammar of the sentence. Keep in mind that verbs end the sentences, so when a Tibetan is writing or speaking, they begin by writing or speaking the nouns and phrases qualified by case markings before they speak or write the verb. There are also a lot of places where, in spoken Tibetan, a volitional verb and a non-volitional verb will sound very, very similar, and one of the key ways one might differentiate between them is what case markings are used.

¶ Clauses

Like sentences, clauses are constructed of a subject and a predicate. This is another way of saying that clauses have a subject (or agent) and a verb. Clauses capture their own grammar – they make their own “box” – and are, in essence, sub-sentences with the larger sentence structure. They can even incorporate other clauses and phrases. Tibetan sentences often have numerous clauses both interwoven dependently or strung together logically to create what might be translated into a paragraph in English.

But, wait? Don't Tibetan sentences only have one verb?! Sort of. Tibetan sentences only have one final or terminal verb. Clauses end in verbals or a core verb followed by a continuative, neither of which are final verbs.

Clauses are sentences that have been modified for use within other sentences. Instead of ending in terminal verbs, they end in either:

- verbal: a verbal noun or adjective

- continuative: a syntactic particle that leads to a continuation of the thought expressed in the clause, such as ནས་, དེ་, or ན་

¶ Clause that end in a verbal

The first type of clause ends in a verbal such as ཡོད་པ་, བྱས་པ་, or སྟོན་པ་. At their most basic, verbals are simply core verbs with a པ་ or བ་ added to it. This turns them into a noun or adjective. It's a bit like saying the falling water where falling is a verbal adjective built from the verb fall. However, in Tibetan, verbals in Tibetan often capture their own grammar and have their own complex syntactical structure, complete with agents, subjects, objects, qualifiers, and complements. So instead of saying The Buddha that taught the dharma in India, one could construct a verbal that says the-dharma-teaching-in-India Buddha. That, obviously, is terrible English (unless you're David Foster Wallace) but it gives a sense of the way verbals are used in Tibetan and the way that a verbal can be used to contain complex grammatical ideas that are formed into a simple adjective.

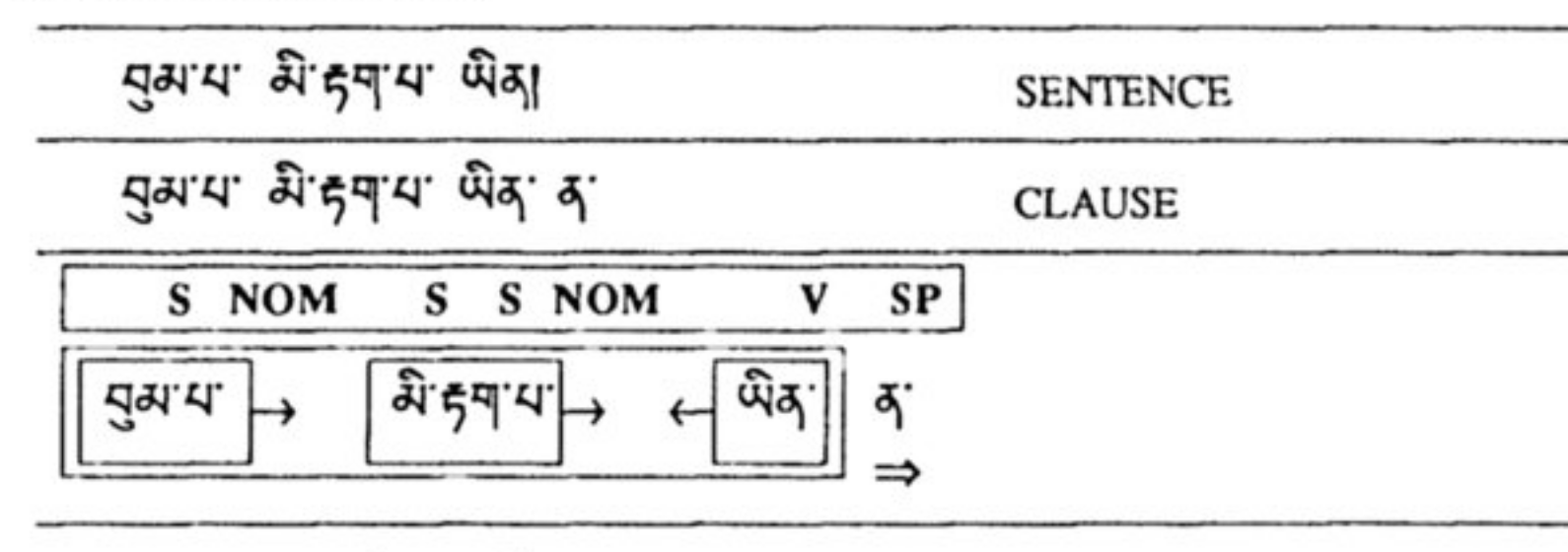

For example, we can turn སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་ཆོས་བསྟན།, which is a sentence that says Buddha taught the doctrine, into a verbal clause that means taught by the Buddha, སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་བསྟན་པ་ (the object, ཆོས་ was removed and a པ་ was added). This clause is actually a complex adjective or noun.

SENTENCE

སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་ཆོས་བསྟན།

Buddha taught the doctrine.

CLAUSE

སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་བསྟན་པ་

taught by the Buddha

The clause itself – as a self-contained unit – thus becomes a noun or an adjective and, as such, may serve as the agent or object of a verb, or even as a noun in a list of nouns. Below is an example of using that clause as a verbal adjective.

VERBAL ADJECTIVE

སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་བསྟན་པའི་ཆོས་

[the] dharma taught by the Buddha

In a very similar construction, the same clause can be used as a verbal noun. Below the clause is set off by the syntactic particle ནི་ and serves as the nominative subject of the verb ཡིན་.

ནི་ is your friend. They are as close as Tibetan gets to true punctuation. They are frequently used to mark the agent or subject of a verb – although, this is certainly not a rule. They are used to emphasize something that precedes the ནི་. They are used to disambiguate syntax, when running two words together might confuse the grammar. Adding the ནི་ makes a clear separation giving you a hint that what is on either side of the ནི་ should be read as separate (this is how the ནི་ is being used below). They are also used in poetry to fill in the meter. Don't confuse ནི་ with ན་.

VERBAL NOUN

སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་བསྟན་པ་ནི་ཆོས་ཡིན།

That taught by the Buddha is the doctrine.

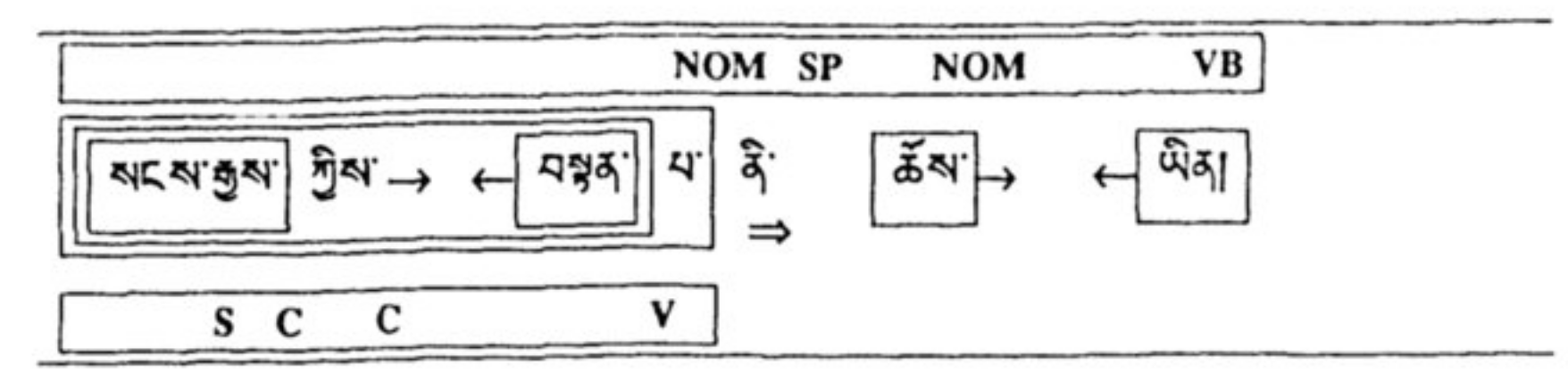

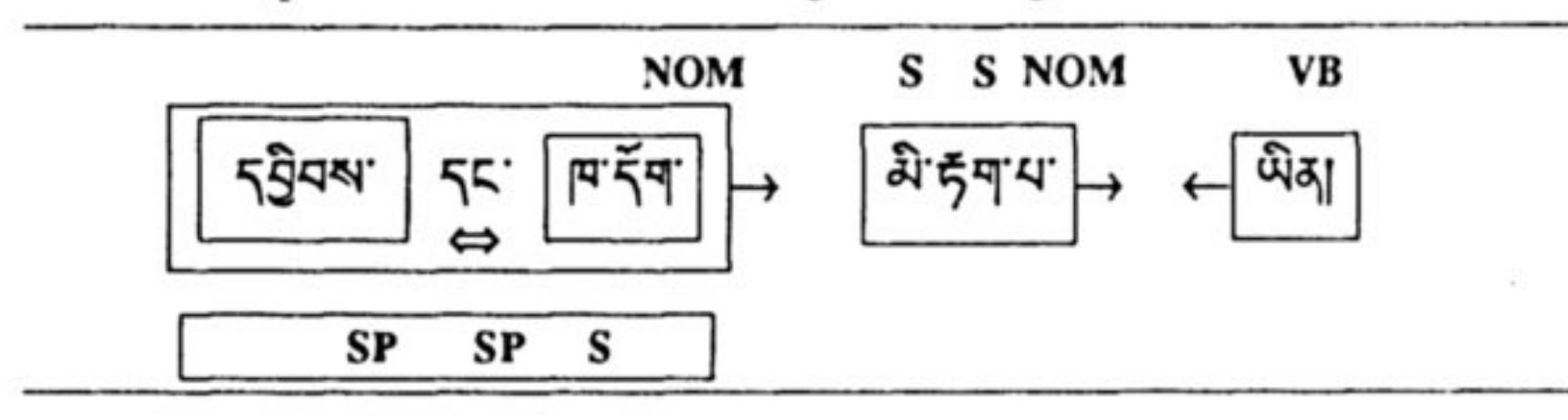

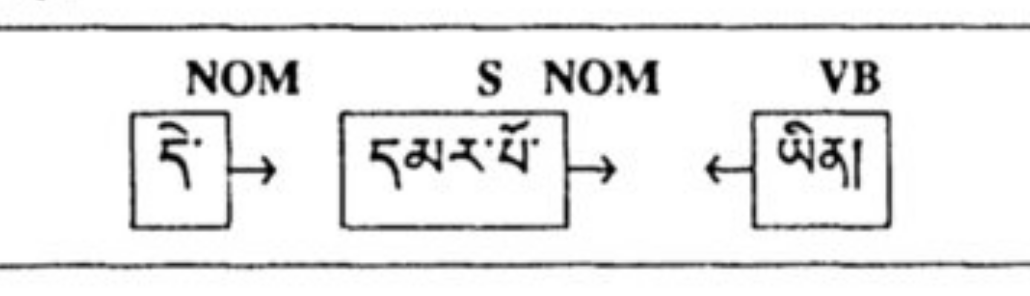

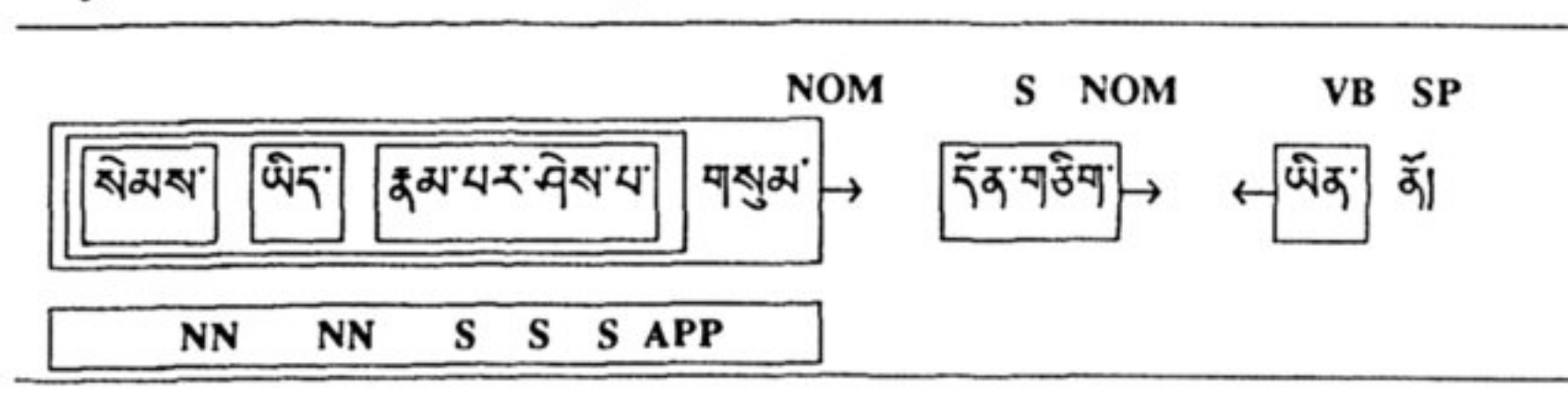

When diagrammed, a clause is contained within its own box and has its own internal grammar.

The box diagram clarifies the way in which the clause, སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་བསྟན་པ་, acts as a single unit and is connected only at its end to the sentence in which it is found. The double arrow under the syntactic particle ནི་ indicates that it operates to the right; that is, the ནི་ marks སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་བསྟན་པ་ as a unit that will be explained further by material following, or to the right of, the ནི་.

Within the clause, the verbal noun བསྟན་པ་ acts as a verb, relating to the words that precede it. (Nouns, in contrast, relate to words that follow it.) The V (Verbal) dot that follows the verbal acknowledges that – the བསྟན་པ་ acts as a noun to its right but as a verb to its left.

ACTS AS NOUN ← བསྟན་པ་ → ACTS AS VERB

Clauses may have their own subjects, complements, and objects. The agentive marking particle (marked with the Case-marker dots) marks the subject of the clause.

As is easily seen in the box diagrams, the grammar inside a phrase or clause is isolated from the sentence in which that phrase or clause is found. It is very helpful to think about these “boxes” when one is trying to translate a Tibetan sentence.

¶ Clause that ends in a continuative or conditional particle

Clauses can also end in a syntactic particle called a continuative, such as ནས་, ཤིང་, or དེ་, or a conditional syntactic particle, such as ན་. Both of these types of particles directly follow a core verb and indicate a logical sequence or dependency.

Continuatives most frequently follow core verbs (less frequently auxiliary verb phrases, and never follow infinitive verb forms). There are three types of continuatives:

ནས་ – frequently used to indicate sequence. It follows a verb whose action has been completed and leads to another clause of sentence which describes a subsequent action.

སྟ་, ཏེ་, and དེ་ – are used to show sequence and, in a more general way, to indicate that something relevant follows. They can be interpreted as a then (A then B) or more as a semicolon, connecting clauses in a sentence that are related but don't necessarily have a strict logical sequence.

ཅིང་, ཞིང་, and ཤིང་ – are used conjunctively after verbs to mean and.

For more continuatives, see Wilson pp. 678-681. For more on conditional syntactic particles, see pp. 669-670. Wilson Appendix 7 on syntactic particles is a great resource for all sorts of syntactic particles.

The conditional syntactic particle ན་ means if or when. Thus “A ན་ B” would mean If A, then B or When A, B.

However, don't forget that ན་ is also one of the la-group particles and can sometimes be used to mark a 2nd, 4th, or 7th case. It is also a verb that means to be sick.

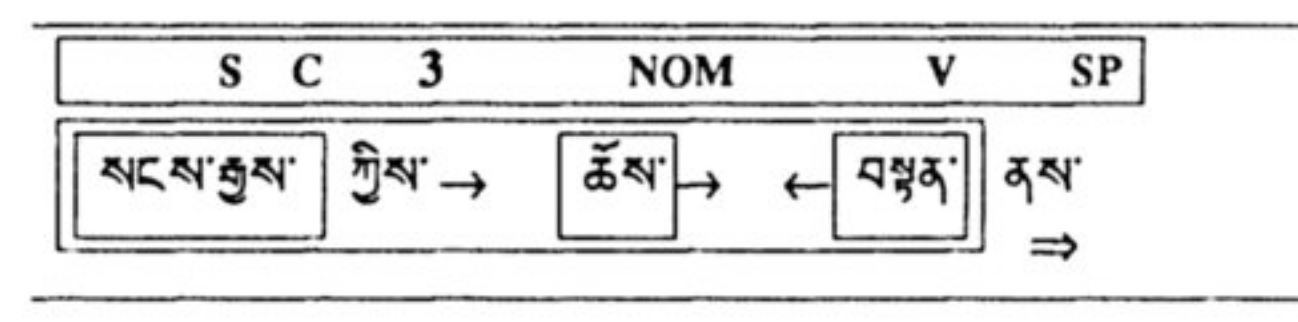

Whereas the sentence སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་ཆོས་བསྟན། expresses a complete thought and ends in a terminal verb, the addition of the syntactic particle ནས་ opens the sentence up, making it merely the beginning of a larger unit.

SENTENCE

སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་ཆོས་བསྟན།

Buddha taught the doctrine.

CLAUSE

སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་ཆོས་བསྟན་ནས་

Buddha, having taught the doctrine…

སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་ཆོས་བསྟན་ནས་ is a clause meaning Buddha, having taught the doctrine…, a clause which sets the stage for the next statement to be made. Thus, the syntactic particle ནས་ is marked with a forward-pointing arrow.

Note the 3 dot after the case marking particle ཀྱིས་. Case dots following case marking particles may be replaced by the number of the case they indicate. Replacing the C dot following but not the C dot preceding the case marking particle highlights the way in which the case marker operates to connect the substantive or adjective they mark to what follows them.

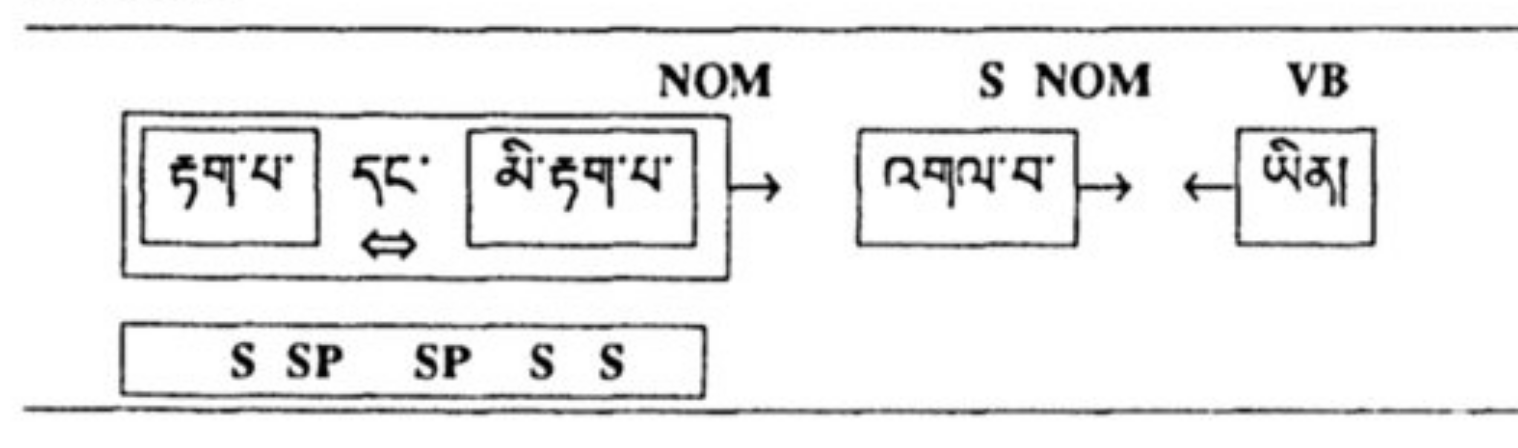

Likewise, where བུམ་པ་མི་རྟག་པ་ཡིན། is a sentence, the addition of the syntactic particle ན་ creates a conditional clause meaning if pots are impermanent or given that pots are impermanent (or technically possibly but likely nonsensical when pots are impermanent).

SENTENCE

བུམ་པ་མི་རྟག་པ་ཡིན།

Pots are impermanent.

CLAUSE

བུམ་པ་མི་རྟག་པ་ཡིན་ན་ …

If pots are impermanent, …

CLAUSE

ཉོན་མོངས་སྤངས་ཏེ་ …

Having abandoned afflictions …

CLAUSE

མངོན་པར་རྫོགས་པར་སངས་རྒྱས་ཏེ་ …

Having become completely and perfectly enlightened, …

Since clauses are actually sentences modified for use as parts of other sentences, most of what has been and will be said about the syntax of sentences also applies to clauses.

¶ Phrases

Phrases are groups of words and syntactic particles that, unlike clauses and sentences, have neither subjects nor predicates. They function as nouns, adjectives, or adverbs within clauses or sentences. They are the simplest groups of words and particles, much simpler than clauses and sentences.

There are phrases made of lists of nouns, noun and adjective phrases, and groups of words ending in syntactic particles that function as adverbs. There are also verb phrases consisting, for example, of compound verbs or verbs with auxiliaries.

Here are some phrases seen in previous chapters.

དགེ་བའི་སེམས་ virtuous mind(s) ADJECTIVE – NOUN

དམ་པའི་ཆོས་ holy doctrine ADJECTIVE – NOUN

སེམས་ཅན་ཀུན་ all sentient beings NOUN – ADJECTIVE

བུམ་པ་དམར་པོ་དེ་ that red pot NOUN – ADJECTIVE

དཀར་པོ་དང་དམར་པོ་ white and red ADJECTIVE + ADJECTIVE

ལས་དང་ཉོན་མོངས་ actions and afflictions NOUN + NOUN

ཤེས་པར་བྱ་ will know VERB + AUXILIARY VERB

ཤེས་ནུས་ able to know COMPOUND VERB

Remember, unlike clauses and sentences, phrases do not have subjects and predicates. Rather, they act as subjects of clauses and sentences or as parts of their predicates.

¶ Noun Phrases

Noun phrases are nouns and adjectives grouped together into a single lexical unit or box. Outside of their box, they act as a single unit, a single noun. Inside the box they have a simple grammar that relates them.

Wilson breaks noun phrases into five types. Craig Preston breaks them into nine types. Below is an introduction to noun phrases. For a more complete treatment, see the wiki page on Noun-Phrases.

Noun Phrases, five types:

- noun-adjective phrases

- lists of nouns

- nouns modified by nouns or pronouns preceding them

- appositive phrases

- nouns modified by adjectives preceding them

¶ Noun-adjective phrase

In Tibetan, adjectives follow the nouns they modify. This is the opposite from English.

བུམ་པ་དམར་པོ་ red pot

NOUN followed by and ADJECTIVE

¶ List phrase (without conjunction)

This is the most simple noun phrase and one of the most common. It is typical in Tibetan for a list of nouns to be simply strung together into a list and treated as a single unit.

ས་ཆུ་མེ་རླུང་ earth, water, fire, and wind

NOUN + NOUN + NOUN + NOUN

¶ List phrase (with conjunction)

Sometimes lists of nouns will be include a conjunction (དང་). In larger lists, the conjunction can occur anywhere in the list (its placement is not structure as it is in English before the last item at the end of the list). Conjunctions are not required.

ས་དང་ཆུ་ earth and water

NOUN + CONJUNCTION + NOUN

Also, དང་ is also used as a syntactic case marking particle to mark the objects of verbs of conjunction and disjunction, so not all དང་'s are and.

¶ Noun-noun phrase

Nouns or pronouns can be connected with another noun using the 6th case. There are a few options as to exactly what relationship is implied by the 6th case used in this fashion: type, possession, apposition, composition, etc. This will be covered extensively later. The two examples below are both 6th case connective of type possession.

སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱི་ཐུགས་ Buddha’s mind

NOUN + CONNECTIVE + NOUN

དེ་ཡི་སེམས་ that one’s mind

PRONOUN + CONNECTIVE + NOUN

¶ Adjective-6th-noun phrase

Adjectives can be placed BEFORE a noun if they are connected with a 6th case (as opposed to AFTER without a 6th case). In this usage, the first word modifies the second and is an exception from our general rule of how Tibetan works.

དམ་པའི་ཆོས་ excellent doctrine

ADJECTIVE + CONNECTIVE + NOUN

¶ Appositive phrase

སངས་རྒྱས་ཚེ་དཔག་མེད་ The Buddha, Amitāyus

NOUN followed by NOUN in apposition

Pluralizing particles, such as རྣམས་, are usually found at the end of a list of nouns. This can be a helpful hint as it usually terminates a noun phrase.

¶ དང་ - the syntactic particle

Sometimes nouns in a list are separated by a conjunction. Unlike and in English, དང་ is optional and, in a list with many values, can be placed anywhere in the list.

དབྱིབས་དང་ཁ་དོག་མི་རྟག་པ་ ཡིན་

Shape and color are impermanent.

དབྱིབས་ shape

ཁ་དོག་ color

མི་རྟག་པ་ impermanent

When used as a conjunction, དང་ is a syntactic particle. Notice the dot after the first of the two nouns in the list above (དབྱིབས་, shape) is an SP dot. The entire list is in the nominative case, but not the separate members of the list. This is analogous to the way མི་རྟག་པ་ as a whole is in the nominative case but the interior syllables of the word are marked with an S dot.

དབྱིབས་དང་ཁ་དོག་[nom] → list as a whole in nominative

དབྱིབས་[sp]དང་[sp]ཁ་དོག་ → inside the “box," SP dots around conjunction

Another way of looking at this is that whereas the noun phrase as a whole is in the nominative, the component words themselves are not. Also notice that the SP dot can be either before or after a syntactic particle. All other dots – the SP dot and the C dot (case marking particle) being the exceptions – are determined only by what they follow, not by what follows them.

Don't assume all དང་'s are a conjunction! དང་ most often means and but can also mean or. Further (or worse, depending on how you feel about Tibetan's enthusiasm for reusing all of its various particles), དང་ is also used with some Class IV nominative-syntactic verbs (verbs of conjunction and disjunction) to mark the qualifier.

Here's that sentence diagrammed with boxes.

Notice the double arrow beneath དང་. That indicates that the conjunction connects what comes before and after it. Remember, however, that the དང་ could come basically anywhere in a list (including nowhere).

Here's a contrived example to demonstrate what I mean using the six tastes (or six taste sense-spheres, རོའི་སྐྱེ་མཆེད།).

མངར་བ་ སྐྱུར་བ་ ཁ་བ་ བསྐ་བ་ ཚ་བ་ ལན་ཚྭ་བ་

sweet, sour, bitter, astringent, pungent, [and] salty

Tibetans will quite happily just run all six of these together:

མངར་བ་སྐྱུར་བ་ཁ་བ་བསྐ་བ་ཚ་བ་ལན་ཚྭ་བ་

Or they might use a དང་ somewhere in the list:

མངར་བ་དང་སྐྱུར་བ་ཁ་བ་བསྐ་བ་ཚ་བ་ལན་ཚྭ་བ་

མངར་བ་སྐྱུར་བ་དང་ཁ་བ་བསྐ་བ་ཚ་བ་ལན་ཚྭ་བ་

མངར་བ་སྐྱུར་བ་ཁ་བ་བསྐ་བ་ཚ་བ་དང་ལན་ཚྭ་བ་

I say this is contrived because with stock lists like this, it's likely they would not use a conjunction at all and would possibly instead finish it with a count of the elements in apposition:

མངར་བ་སྐྱུར་བ་ཁ་བ་བསྐ་བ་ཚ་བ་ལན་ཚྭ་བ་དྲུག་

sweet, sour, bitter, astringent, pungent, [and] salty – the six

Here's another simple example of དང་ being used as a conjunction.

རྟག་པ་དང་མི་རྟག་པ་འགལ་བ་ ཡིན་

Permanent and impermanent are mutually exclusive.

འགལ་བ་ mutually exclusive

རྟག་པ་ permanent

མི་རྟག་པ་ impermanent

In the next example, the subject is a clause and the complement is a compound.

སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱི་ཆོས་ནི་ ལུང་དང་རྟོགས་པའི་ཆོས་ ཡིན།

SUBJECT COMPLEMENT LINKING VERB

Buddha's doctrines are the scriptural and realized doctrines.

ལུང་ scripture, āgama; has a sense of transmission in a lineage passed down verbally instead of revelation

Notice how the 6th case (འི་) in the complement distributes to both of the elements of the list (ལུང་དང་རྟོགས་པ་) – or, thinking about it another way, the 6th connects to the list as a whole, not to the individual elements.

The 6th case is an example of the type connective. What type of ཆོས་? The type which is the individual Buddhist's realization of what the Buddha taught in scripture.

ལུང་ (āgama) is an important word in Tibetan. In general it means scripture, but not in the Western sense of revelation. ལུང་ has a sense of transmission, of a tradition of understanding passed down verbally from one generation to another – from teacher to student, “warm heart to warm heart” as Yangsi Rinpoche says. In Tibetan Buddhism, as in Buddhism in general, scripture is not so much something read as it is spoken and heard.

The locus classicus (that is, the original textual source) for this distinction is Vasubandhu's Abhidharmakośa (Treasury of Advanced Knowledge), 8:39 (that is, chapter 8, verse 39). The context in which this is appropriated in Tibetan Buddhism is the explanation of taking refuge. The actual refuge from the suffering of cyclic existence is the doctrine, specifically the realized doctrine. See, for example, HH Tenzin Gyatso, The Dalai Lama at Harvard, pp. 16, and Geshe Rabten, Treasury of Dharma, pp. 78-79.

ལུང་ is very close to རླུང་, which means wind. It has both the meaning of the wind element (vāyu) and the vital energy (prāṇa) as well as simply wind (the movement of air). The definition of རླུང་ is light and motile, ཡང་ཞིང་གཡོ་བ་.

¶ Things left unsaid

As was mentioned earlier, the agent of a sentence is often unstated. Sometimes this is because the agent is the Buddha. Other times this is because the agent is known from a previous sentence. However, this is part of a larger pattern in classical Tibetan. The final linking verb of a sentence (typically ཡིན་) is very frequently omitted.

Classical Tibetan is often very terse and abbreviated. Many things in Classical Tibetan are unstated if they can be inferred – or if they could be inferred by a Geshe.

These works were hand carved into wood blocks. They also had to be memorized. Further, these works were not meant to be read in the way modern books are read, but are meant to be memorized and passed down in the context of a lineage of teachers who have both practiced and studied the works, generating both conceptual knowledge and deep realization. They are often mnemonic devices as much as books in the modern sense.

Thus there is no expectation that someone could read the work without prior knowledge of it and understand it's meaning. All of this means that in actual Tibetan Buddhist works, the reader is expected to be able to infer from context many things that may not initially be obvious to us as translators.

¶ Nouns and Adjectives

Adjectives are exceptions to the rule that all words except verbs relate to what follows them and not to what precedes them. Adjectives generally follow the nouns they modify. They generally relate to what directly precedes them.

NOUN-ADJECTIVE.

བུམ་པ་དམར་པོ་ [pot-red]

red pot

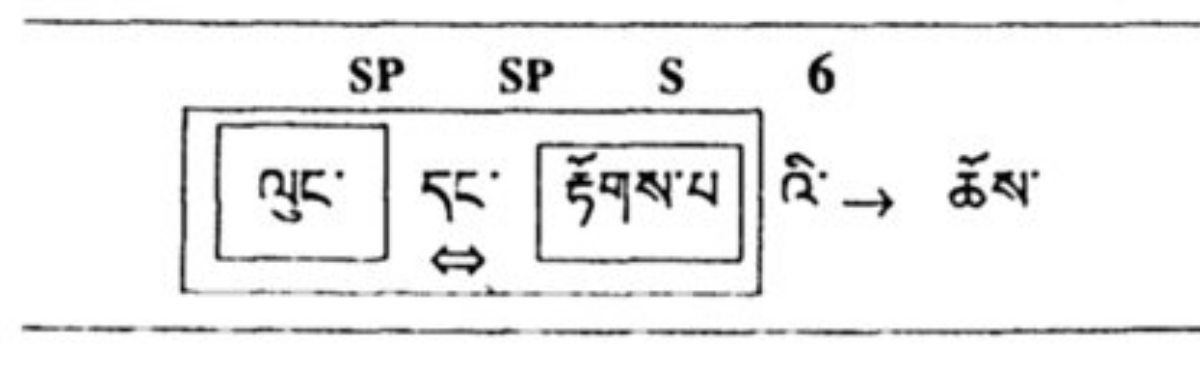

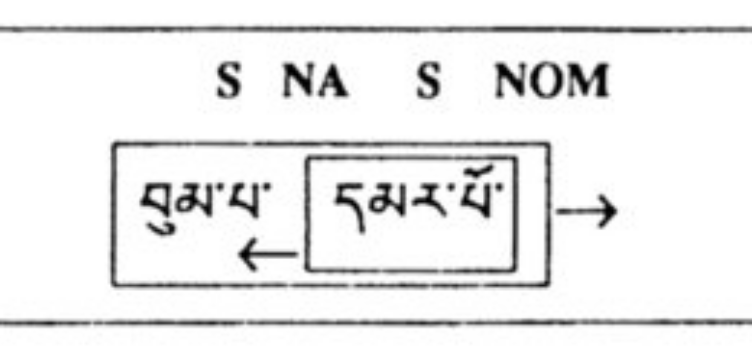

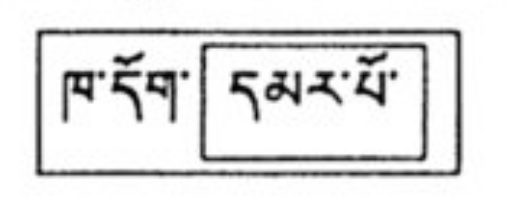

This is the simplest type of noun phrase in Tibetan. Notice how the outer box around the entire noun phrase points to the right while the inner box around the adjective (དམར་པོ་) points to the left. It is the phrase as a whole (བུམ་པ་དམར་པོ་) that is in the nominative case, while inside the noun-adjective phrase there are two S dots and a NA (noun-adjective) dot.

It is possible for an adjective to precede a noun. In that case it is connected to the noun with a sixth case.

ADJECTIVE-6TH CASE-NOUN

དམ་པའི་ཆོས་ [excellent-doctrine]

excellent doctrine, doctrine of the excellent

ADJECTIVE-6th-NOUN is less common than NOUN-ADJECTIVE and does not work with all nouns and adjectives. For example, look at the following, which means the red one's pot or pot of the red one and not red pot.

དམར་པོའི་བུམ་པ་

pot of [that is, belonging to] the red one – not red pot

¶ Noun or Adjective

Tibetan adjectives are modifiers and, as such, they must modify a noun. However, as in English, they can act as substantives. The adjectives དེ་ and འདི་ often act as pronouns meaning that and this. Adjectives like དམར་པོ་ can do this as well where བུམ་པ་དམར་པོ་ means red pot, ཁ་དོག་དམར་པོ་ means the color red, which is an appositional noun phrase.

ཁ་དོག་དམར་པོ་ the color red

appositional noun phrase

Consider the next example:

དེ་དམར་པོ་ཡིན།

THAT – RED – IS

That is red.

དེ་ is an example of an adjective being used as a pronoun. དམར་པོ་ is an example of a predicate adjective – that is, an adjective being the complement of a linking verb. However, it is possible, depending on context, to interpret this sentence differently, and to read དམར་པོ་ as a noun (instead of as an adjective). If the subject being discussed is a color, the sentence could read That one is [the color] red. The distinction is between (1) reading དམར་པོ་ as a predicate adjective that modifies the pronoun དེ་ (that), and (2) reading དམར་པོ་ as a noun, the color itself, and saying that དེ་ (that) is the color red.

The question of predicate adjectives in Tibetan is a fraught situation. When speaking loosely, in Tibetan, as in English, one can use predicate adjectives. That is, one can say things like, The car is red. However, when one gets into the basic of debate and the Collected Topics literature (བསྡུས་གྲྭ་), literally the first debate explodes the errors in this type of statement. The debate doesn't use a car, of course, but uses a white religious conch.

One cannot say A white religious conch is white because a conch is not a color. Just as one cannot say The car is red because the car is not a color. Strictly speaking, one must say The color of a white religious conch is white and The color of a red car is red. Red is a color and only a color can have the quality of being it. Both the car and the color red abide in the same entity just as both the conch and the color white abide in the same entity, inextricably linked. Yet there is no phenomenon that is both the car and the color red just as there is no phenomenon that is both the conch and the color white.

The two phenomena (the car and the color red or the conch and the color white) are conceptually isolate-able within being one entity. This distinction might seem pedantic at first but it is not. It actually strikes at the heart of the Buddhist of emptiness and no-self.

Nonetheless, in either case the construction is the standard linking verb construction: SUBJECT + COMPLEMENT + VERB, and the sentence is diagrammed in the same way.

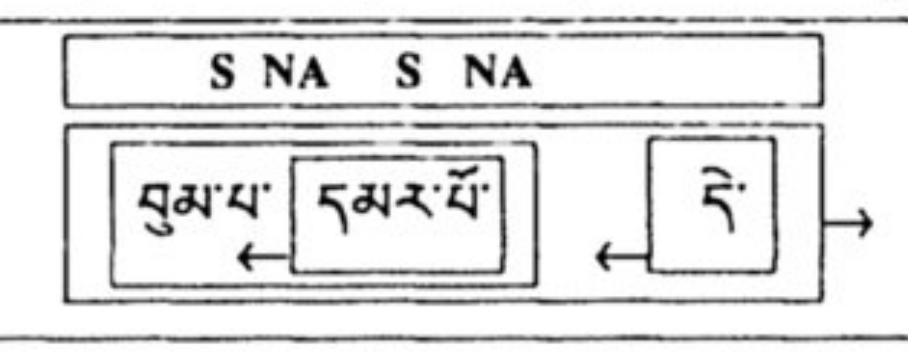

Adjectives can also be used to qualify not only simple nouns but also noun-adjective phrases, as in the phrase བུམ་པ་དམར་པོ་དེ་. The basic NOUN + ADJECTIVE phrase is བུམ་པ་དམར་པོ་, which then, as a unit, is modified by the adjective དེ་.

Thus དེ་ modifies the entire phrase preceding it (བུམ་པ་དམར་པོ་) and not just the immediately preceding word (དམར་པོ་). The word order is important. If the དེ་ were moved to modify བུམ་པ་, like this བུམ་པ་དེ་དམར་པོ་, it would say That pot [is] red (filling in an omitted ཡིན་).

Word order is important with nouns and adjectives.

བུམ་པ་དམར་པོ་དེ་ that red pot

[pot-red-that]

བུམ་པ་དེ་དམར་པོ་ཡིན། that pot is red

[pot-that-red-is]

¶ Appositives

It's very important to understand apposition. It is used all throughout Tibetan. The definition from the Oxford dictionary is:

- [technical] the positioning of things or the condition of being side by side or close together.

- [grammar] a relationship between two or more words or phrases in which the two units are grammatically parallel and have the same referent (e.g. my friend Sue ; the first US president, George Washington ).

Apposition is an example of a noun qualifying a noun (instead of an adjective modifying a noun, which is more typical). For example, in our canonical example appositional phrase The Buddha Amitāyus, Amitāyus qualifies The Buddha. Which Buddha? Amitāyus. This is the same if we said our friends Craig, Bill, and Paul. our friends is in apposition to Craig, Bill, and Paul – both of which refer to the same object (or set of objects, in this case). Which friends? Craig, Bill, and Paul.

སངས་རྒྱས་ཚེ་དཔག་མེད་ the Buddha Amitāyus

ཁ་དོག་དམར་པོ་ the color red

As with nouns in a list, we have two (or more) nouns (or noun phrases), one after the other. Just like with nouns in a list, the appositional noun phrase is considered a unit in the larger structure of the sentence outside of the noun phrase. However, the relationship between the nouns in apposition is very different than the relationship between the nouns in nouns in a list. In the case of apposition, one noun narrows the other (which color? the color red). The relationship between the nouns in a noun list is often contextual or based on a philosophical grouping (earth, water, fire, and wind, for example), not on any direct lexical relationship.

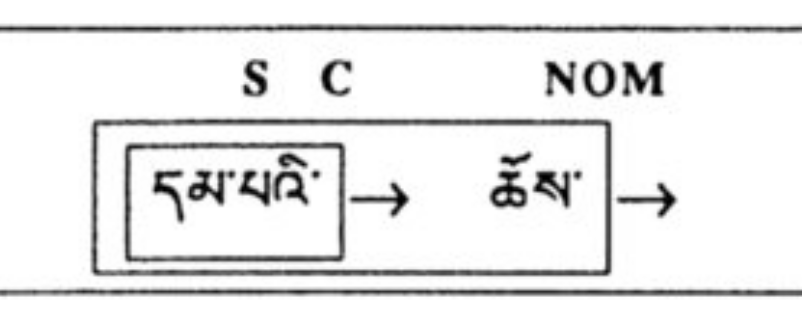

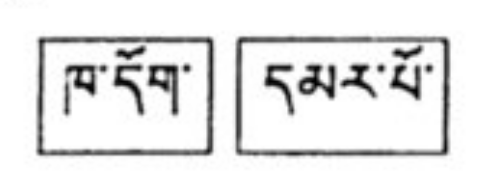

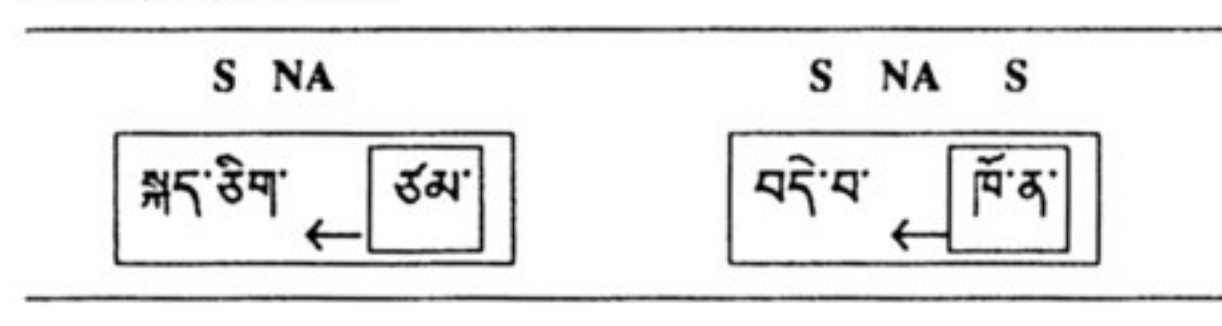

ཁ་དོག་དམར་པོ་ is diagrammed as follows:

In this example the main word is color. Color is the general term that is clarified by red. Thus, the box around ཁ་དོག་ also encloses དམར་པོ་ (but not vice versa). However, unlike a NOUN-ADJECTIVE phrase, there is no arrow from དམར་པོ་ to ཁ་དོག་. Red does not modify the noun color in the same way red modifies apple in red apple. In apposition, both terms are at almost the same level.

It would be incorrect to diagram this appositive phrase (seen below) with two separate boxes because they do not act as separate units in the sentence.

So far in our examples, the second word has narrowed the first. Or, to put that another way, the general term was the first term followed by the more specific term. This is not always the case. In the example below, which represent a VERY common construction, a list of specific items is followed by a count of the number of items in the list, where the count is in apposition to the list.

སེམས་ ཡིད་ རྣམ་པར་ཤེས་པ་ གསུམ་ དོན་གཅིག་ ཡིན་ ནོ།

Mind, mentality, and consciousness – the three – are equivalent.

mind, mentality, and consciousness [APP ] the three

When diagrammed as above, it is easy to see that three (གསུམ་) is in apposition to the entire list, not simply to the word that precedes it.

¶ Subjective Suffix Syllables

པ་, པོ་, བ་, བོ are subjective suffix syllables and can be added to the ends of word to create new words specifying:

- agency

- ownership

- composition

- membership (literal or metaphorical)

Very broadly, they can be thought of as nominalizers that turn a verb into a noun. In some cases these nouns are indistinguishable from ordinary nouns with the same suffix ending.

For example, where མཁས་ is a verb meaning be skilled, the verbal noun མཁས་པ་ means scholar – one who is skilled or one who possesses skill. Likewise, where རྒྱལ་ is a verb conquer, རྒྱལ་པོ་ is king – one who conquers. རྒྱལ་མོ་, incidentally, is queen. མོ་ is sometimes used as a female nominalizer, as in this case. རྒྱལ་བ་, or, conqueror, is often used to refer to a Buddha.

Sometimes you see words with an “extra” nominalizer, such as ཤེས་པ་པོ་.

- ཤེས་ is a verb know.

- ཤེས་པ་ is a noun knowledge.

- ཤེས་པ་པོ་ is another noun one who knows or knower.

Similarly འཆད་པ་པོ་:

- འཆད་ (v) explain

- འཆད་པ་ explanation

- འཆད་པ་པོ་ explainer or commentator

The noun-adjective phrase ཐེག་པ་ཆེན་པོ་ means Great Vehicle or Mahāyāna. The derived word ཐེག་པ་ཆེན་པོ་པ་ means Mahāyānist or one who practices the Great Vehicle.

The generic translation for these type of nominalized words is: someone or something having to do with X. Thus, if དབུ་མ་ means middle, དབུ་མ་པ་ means someone or something having to do with the middle. In fact, དབུ་མ་པ་ refers to an adherent of the Middle Way tenet system or to the tenet system itself.

ཅན་ and མཁན་ are the two other subjective suffix syllables. The former is very common, the latter less so (more common in spoken language). They are added at the ends of words, after which case marking particles can be added.

ཅན་ means possessing. སྐྱོན་ means fault. སྐྱོན་ཅན་ means possessing fault(s) or flawed. This can then be declined by a case marking particle to indicate a function, such as སྐྱོན་ཅན་ལ་ or སྐྱོན་ཅན་གྱི་.

མཁན་ is used to show a type of agency, as in one who X. For example, using the verb བྱེད་ (to do), བྱེད་མཁན་ means one who does. Or, using ཡིག་, which is a noun letter. ཡིག་མཁན་ means scribe or secretary.

མཁས་ means be skilled

མཁས་པ་ means scholar—that is, one who is skilled, one who possesses skill

རྒྱལ་ (v) conquer

རྒྱལ་པོ་ king (clearly used to mean one who conquers)

རྒྱལ་བ་ conqueror

ཤེས་ (v) knowཤེས་པ་ knowledge

ཤེས་པ་པོ་ knower

འཆད་ (v) explain

འཆད་པ་ explanation

འཆད་པ་པོ་ explainer or commentator

ཐེག་པ་ཆེན་པོ་ Great Vehicle, Mahāyāna

ཐེག་པ་ཆེན་པོ་པ་ Mahāyānist

དབུ་མ་ middle

དབུ་མ་པ་ Middle Way tenet system and it’s adherents

ཅན་ is another common suffix syllable that means possessing

སྐྱོན་ཅན་ possessing faults or flawed

¶

¶ Restrictive Suffix Syllables

ཉིད་ is the one true restrictive suffix syllable. As a final syllable, ཉིད་ sometimes means just and sometimes creates abstract nouns (-ness, as in emptiness).

དེ་ཉིད་ just that, that itself

ཉིད་ can also intensify what is already stated (and is untranslatable). For example, རང་ means itself, and so does རང་ཉིད་

ཉིད་ also creates abstract nouns—words that express an ideal or characteristic by itself, without speaking of something having that characteristic. The rule of thumb is to translate as –ness.

སྟོང་པ་ empty, śūnya

སྟོང་པ་ཉིད་ emptiness, śūnyatā

དེ་ཉིད་ just that, reality [that-ness], tattva

བདག་ཉིད་ essence, nature [self-ness]

Note an important exception here. མཚན་ཉིད་ (definition, characteristic), which is neither an abstract noun nor just something. (Although, thinking about this as “defining characteristic mark”, as Berzin likes to translate it, you can see how it could be just-defining-characteristic-mark)

མཚན་ཉིད་ definition, characteristic, lakṣaṇa

ཙམ་ and ཁོ་ན་ are the two remaining restrictive particles. They mean just or only or merely.

དེ་ཁོ་ན་ཉིད་ ultimate reality, just-that-ness

སེམས་ཙམ་ mind only

Most occurrences of ཙམ་ and ཁོ་ན་ are not as lexical particles (that is, part of the word itself) but as adjectives in noun-adjective combinations, meaning just or only. ཉིད་ is also often used as an adjective as well. The examples below are not single words but two words joined together in a noun-adjective phrase.

སྐད་ཅིག་ཙམ་ only a moment [instant/moment-only]

བདེ་བ་ཁོ་ན་ bliss alone

ཆོས་ཉིད་ reality, dharmatā (the nature of phenomena, or phenomena-ness)