¶ Chapter 10 – Lexical, Syntactic, and Case Marking Particles

ཚིག་ཕྲད་ traditional Tibetan study of particles

In our system (a little narrower than ཚིག་ཕྲད་), there are three main classes of particles:

- lexical particles

- case marking particles

- syntactic particles

¶ Lexical Particles

Lexical particles are units, usually made up of one or two syllables, that serve as parts of words. They do not function independently of words.

For example, བུམ་པ་ may be made plural by adding a lexical particle: བུམ་པ་རྣམས་

The following examples illustrate the use of particles:

བློ་ mind

ཡུལ་ object (also place and region)

ཡུལ་ཅན་ subject [object-possessor]

རྟོག་པ་ thought, conceptuality

རྟོག་བཅས་ conceptual

རྟོག་མེད་ non-conceptual

ཅན་ means possessing. ཡུལ་ཅན་ literally translates as “object possessor”.

བཅས་ also means possessing but is short for དང་བཅས་པ་, thus རྟོག་བཅས་ is actually རྟོག་དང་བཅས་པ་, meaning possessing conceptuality.

¶ The five types of lexical particles

1. prefix particles, such as རྣམ་པར་ in རྣམ་པར་ཤེས་པ་ (consciousness)

2. negative prefix particles, such as མ་ in མ་ཡིན་

3. final syllables, such as the པ་ in བུམ་པ་ and ཡོད་པ་; and the three syllable particle དང་བཅས་པ་ in རྟོག་པ་དང་བཅས་པ་

4. optional suffix syllable, such as pluralizers དག་ and རྣམས་

5. negative verbal particles, such as མེད་པ་ in རྟོག་པ་མེད་པ་ (without conceptuality, abbreviated རྟོག་མེད་)

In general, Tibetan words beginning with prefix particles, two-syllable lexical particles like རྣམ་པར་, རྗེས་སུ་, ཀུན་ཏོ་, and མངོན་པར་, are Tibetan translations of Sanskrit Buddhist terms. You will learn to recognize these prefixes.

མངོན་པར་རྟོགས་ → verb: realize

མངོན་པར་རྟོགས་པ་ → noun: realization

མ་ཡིན་ → verb: is not

མ་ཡིན་པ་ → noun: not being, as used in རྟག་པ་མ་ཡིན་པ་ (not being permanent, or non-permanent [phenomenon])

¶ Verbal Nouns and Adjectives

Any word ending in one of these final syllables is either a noun or an adjective: པ་, པོ, བ, བོ, མ, མོ.

Final verbs never end in these syllables.

Many nouns and adjectives are made by affixing one of these syllables to a verb. These are called verbals.

Whereas མེད་ means to not exist, མེད་པ་ means nonexistent.

Verbals act like verbs in many ways. They may have subjects and objects, but they are nouns or adjectives and are themselves the subjects or objects of other verbs.

ACT AS VERB ← VERBAL → ACT AS NOUN OR ADJECTIVE

To their left, they can create their own “box” or “glue," acting as a verb determining the grammar of a phrase (although that box is often subsumed within the larger box of the final verb of the sentence); and to their right, they act as a noun or adjective, controlled by the grammar of the larger sentence.

བསྟན་ can be made into a verbal བསྟན་པ་

སངས་རྒྱས་རྐྱིས་ཆོས་བསྟན་ The Buddha taught the doctrine.

སངས་རྒྱས་རྐྱིས་ཆོས་བསྟན་པ་ Buddha’s having taught the doctrine…

སངས་རྒྱས་རྐྱིས་བསྟན་པ་ taught by the Buddha..., that taught by the Buddha...

¶ Syntactic Particles

Syntactic particles do not have their own lexical meaning. They are used to connect words, phrases, and clauses to one another. They are not part of words—yet cannot function independently of words. They take their full meaning only when used with other words.

¶ Connects nouns, pronouns, and adjectives.

དང་ and

དཀར་པོ་དང་དམར་པོ་ white and red

¶ Introduce phrases, clauses, and sentences:

གཞན་ཡང་ moreover

དེས་ན་ therefore

ཡང་ན་ alternatively

¶ Similar to a punctuation mark:

ནི་ like a colon, also often used to mark the agent of a sentence off from the rest of a sentence

མི་རྟག་པ་ནི་ – མི་རྟག་པ་ is the topic to be discussed and the discussion will immediately follow the ནི་

ནི་ may also mark the noun or noun phrase as a section heading

¶ Ends clauses that present a reason:

ཕྲིར་ because

ཡོད་པའི་ཕྲིར་ because of existing

ཕྲིར་ is one of the most common syntactic particles in philosophical texts, since it ends clauses that present reasons. Like the postpositions, it is connected to the clause it ends with a connective case marking particle. However, unlike the postpositions, it is not declined.

¶ Terminators, function like a period:

ནོ་ ངོ་ དོ་ ཏོ་ མོ་ འོ་ རོ་ ལོ་ སོ་

Terminators are your friends. The first step in translating a sentence in Tibetan is fininding the end of the sentence and the closed or terminal verb. The entire structure of the sentence flows from this point in the same way all of the leaves and limbs of a tree from from the trunk in the ground. Terminators definitively mark the end of a sentence and will always (excpetions?) follow the terminal verb of a sentence.

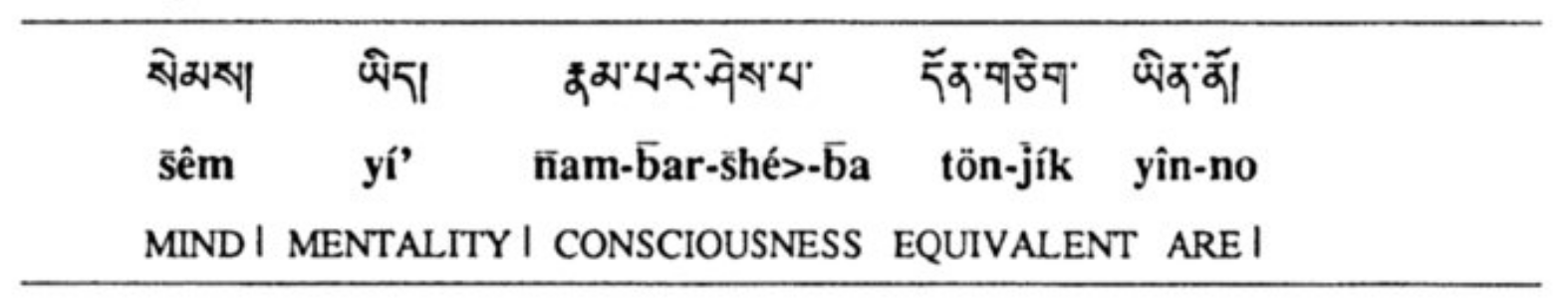

Here is an example. Notice the ནོ after the terminal verb དོན་གཅིག་. This is as close as Tibetan gets to having a period.

སེམས་ཡིད་རྣམ་པར་ཤེས་པ་དོན་གཅིག་ནོ། Mind, mentality, and consciousness are equivalent.

¶ The Science of the Dots

The science of the dots is a way of speaking about the relationship between syllables within words and between words as if the dots following the syllables and words actually had different functions. This is not actually the case. The “dots” do not actually perform any other function except separating syllables. This is merely a metaphor for speaking about the grammar of a sentence.

It is possible to identify each dot in Tibetan sentence in terms of either:

- the type of syllable it follows, or

- the relationship between the syllable it follows and the rest of the phrase, clause, or sentence in which it is found.

Five most basic functions of the dots:

S - between syllables within words, particles, and verb phrases

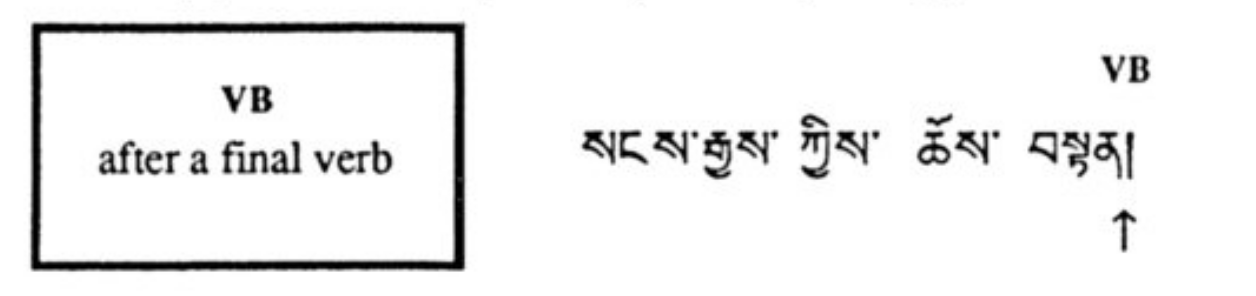

VB - after a final verb

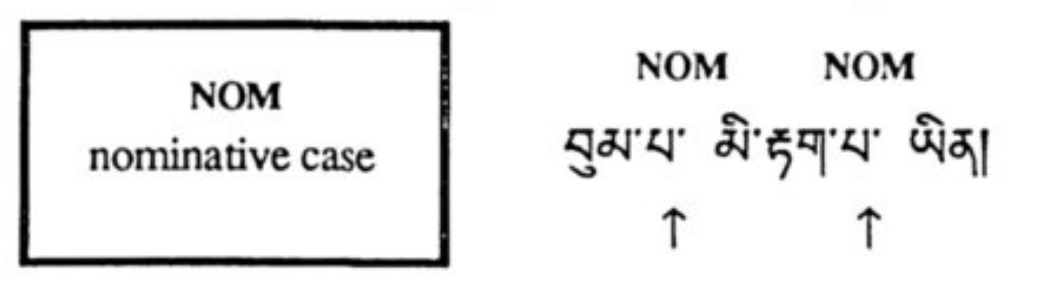

NOM - after a noun in the nominative case

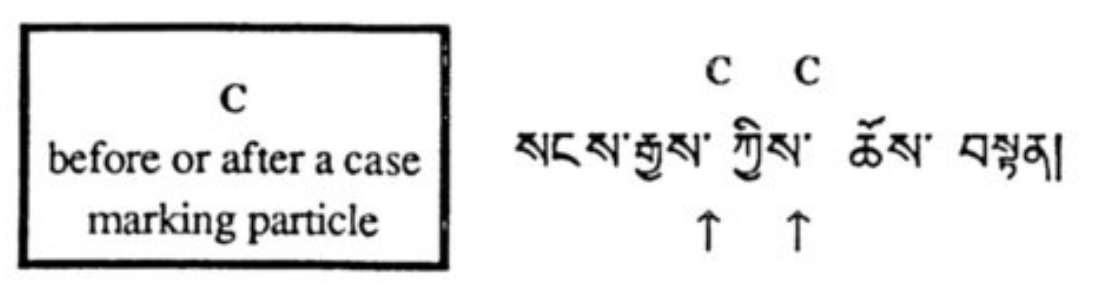

C - before or after a case-marking syntactic particle

SP - before or after a syntactic particle other than a case marking particle

The complete list

S - between syllables within words, particles, and verb phrases

OM - omitted syllable in a contraction or abbreviation

---

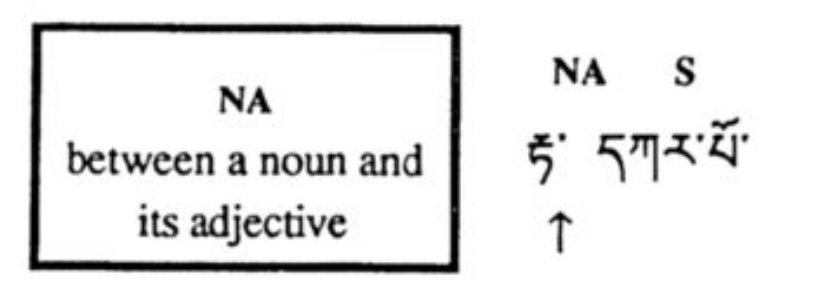

NA - between a noun and adjective modifying that noun

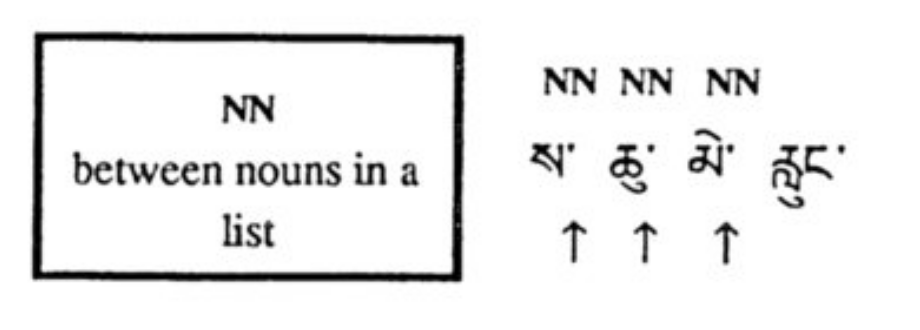

NN - between nouns in a list

APP - between two words or phrases in apposition

---

VB - after a final verb

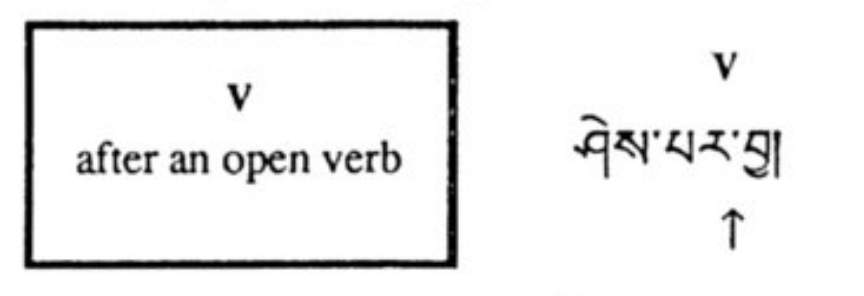

V - after an open verb

ADV - after an adverb or after a particle marking adverbial identity

---

NOM - after a noun in the nominative case

VOC - after a noun in the vocative case or an interjection

C - before or after a case-marking syntactic particle

UP - indicating an understood case marking or syntactic particle

---

SP - before or after a syntactic particle other than a case marking particle

¶ Lexical Dots

The first group, S and OM dots, are found only within words and particles, the lexical dimension of analysis. They do not act in the syntactic dimension (as part of the larger grammar of phrases, clauses, and sentences).

Identifying S and OM dots is essentially learning to identify words. Once the S and OM dots have been identified (once the words have been identified), the syntax of the sentence can begin to be understood.

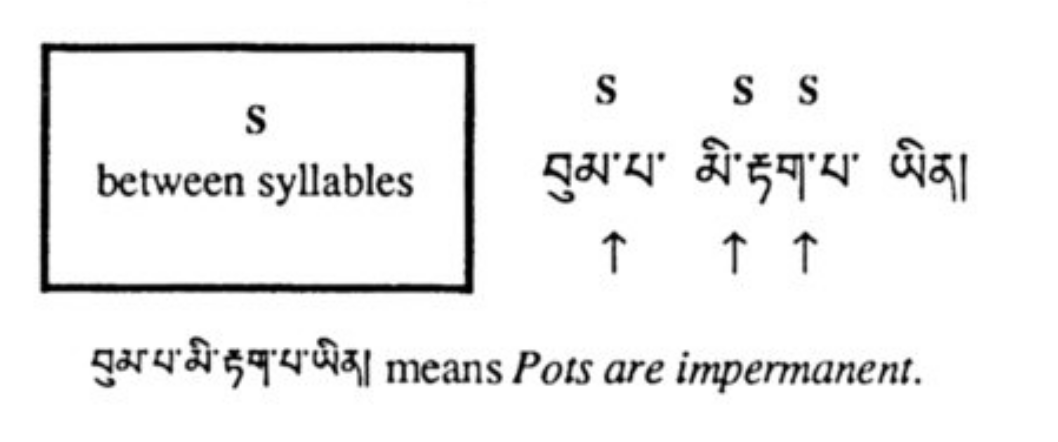

There are three S dots in the sentence Pots are impermanent.

བུམ་[s]པ་ མི་[s]རྟག་[s]པ་ ཡིན།

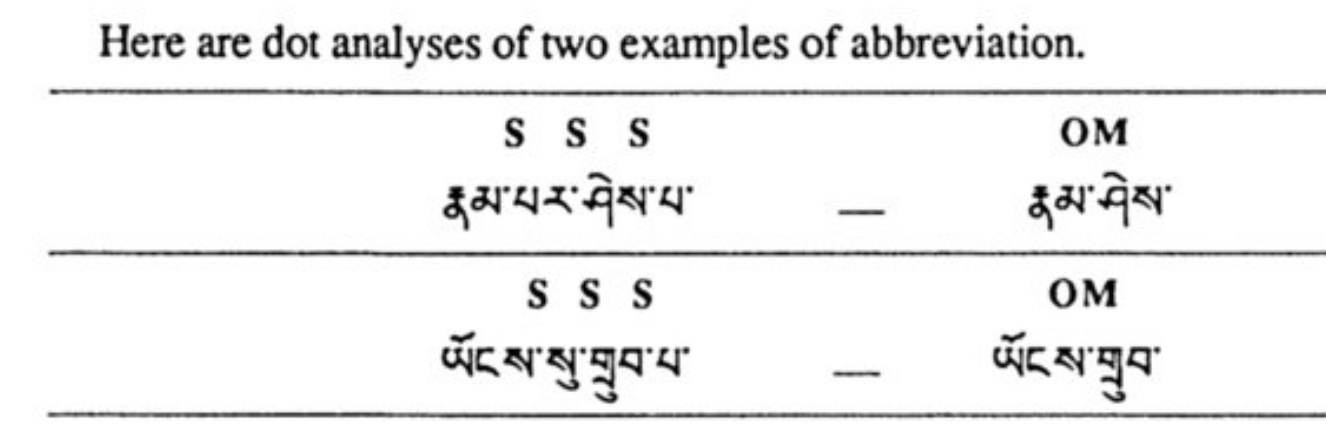

Abbreviation of words and phrases is very common in classical Tibetan. Remember: they were memorizing all of this stuff and carving it into wood blocks! The OM dot marks a syllable where other syllables are understood to have been omitted.

རྣམ་པར་ཤེས་པ་ → རྣམ་[om]ཤེས་

¶ Dots within Noun Phrases

NA, NN, and APP dots occur within certain types of noun phrases (noun-adjective phrases, list phrases, and appositional phrases).

Example of an NA dot (noun-adjective phrase):

རྟ་དཀར་པོ་ → རྟ་[na]དཀར་[s]པོ་

Example of a NN dot (nouns in a list):

ས་ཆུ་མེ་རླུང་ → ས་[nn]ཆུ་[nn]མེ་[nn]རླུང་

earth, water, fire and wind

¶ Dots used with Verbs and Adverbs

The third, fourth, and fifth group of dots are true syntactic dots. They show how words relate to one another in the larger syntax of a clause or sentence.

The third group of dots (VB, V, and ADV) occur after verbs, within verb phrases, or after adverbs.

VB is found after complete verbs or final verbs (ཤེས་) or verb phrases (ཤེས་པར་བྱ་).

སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་ཆོས་བསྟན།[vb]

V occurs after open or incomplete verbs that are not terminal:

- after infinitives (such as རྟོགས་པར་ in རྟོགས་པར་དཀའ་, difficult to realize)

- between the components of verb phrases (ཤེས་པར་ in ཤེས་པར་བྱ་, will know)

- after verbals at the end of clauses

- after verbs preceding continuative syntactic particles (བསྟན་ནས་, having taught; བསྟན་ན་ if/when taught).

V used after an open verb:

ཤེས་པར་[v]བྱ།[vb]

What's the unmarked dot?

¶ Dots and Declension

NOM, VOC, C, and UC (the fourth group) are used when nouns, pronouns, and adjectives are declined. NOM and VOC follow the nominative and vocative cases, respectively. Both of these cases are identified by the fact that no case particle is used to mark them.

NOM - nominative case:

བུམ་པ་[nom]མི་རྟག་པ་[nom]ཡིན།

The other six cases are marked by case marking particles. The dots before and after the case marking particles are C dots. Sometimes case particles are dropped or omitted. In this case, the dot where the case particle would have been is seen as a UC dot (understood case).

སངས་རྒྱས་[c]ཀྱིས་[c]ཆོས་བསྟན།

¶ Dots Used with Syntactic Particles

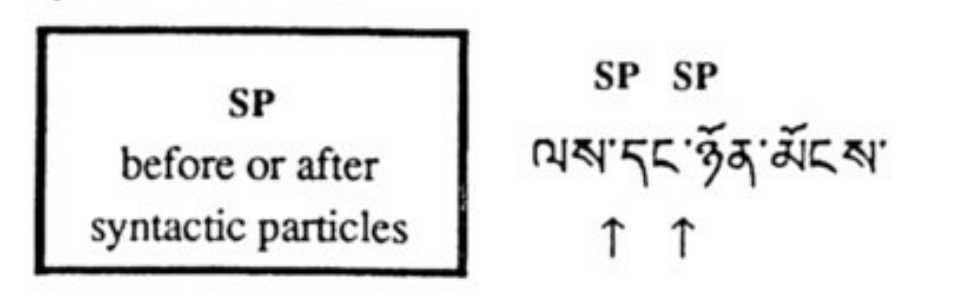

SP dots (the fifth group) is just one dot that marks before and after syntactic particles.

SP - syntactic particle dots:

ལས་[sp]དང་[sp]ཉོན་མོངས་

དང་ is a conjuction meaning and but can also mean or.

ལས་དང་ཉོན་མོངས་ – actions (karma) and the afflictions – are the two causes of cyclic existence.

¶ Pattern Analysis - Nouns in a List

Nouns are frequently strung together in a list in Tibetan. There are no real punctuation marks, as in English. Sometimes a list will be separated as the following:

སེམས། ཡིད། རྣམ་པར་ཤེས་པ་དོན་གཅིག་ཡིན་ནོ།

MIND MENTALITY CONSCIOUSNESS EQUIVALENT ARE

But more frequently you will see the nouns in a list without any spacing or separation.

སེམས་ཡིད་རྣམ་པར་ཤེས་པ་དོན་གཅིག་ཡིན་ནོ།

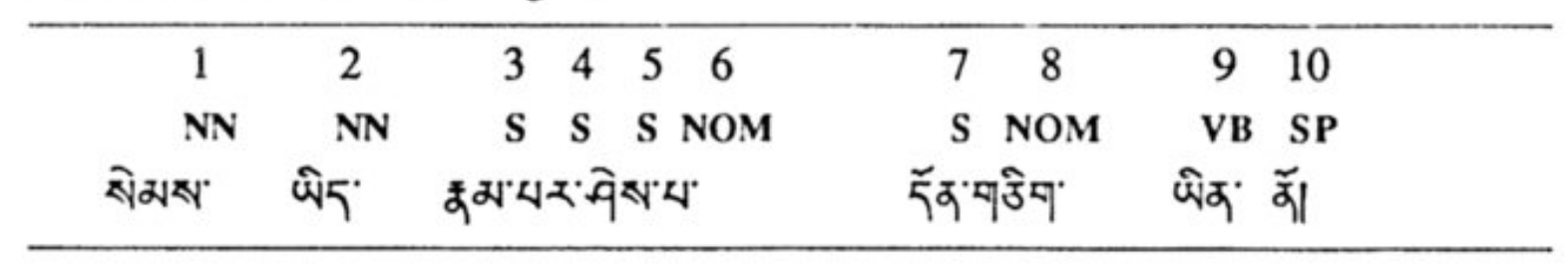

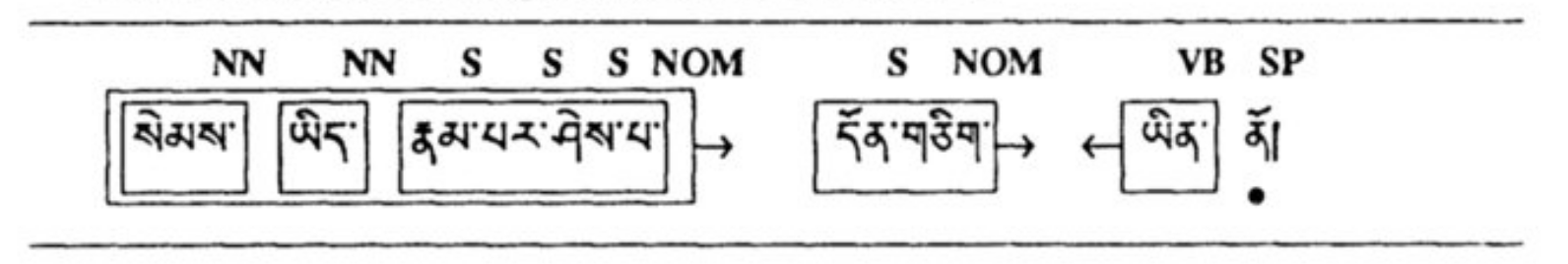

Here is a dot analysis of that sentence:

སེམས་ཡིད་རྣམ་པར་ཤེས་པ་དོན་གཅིག་ཡིན་ནོ།

སེམས་[nn]ཡིད་[nn]རྣམ་[s]པར་[s]ཤེས་[s]པ་[nom]དོན་[s]གཅིག་[nom]ཡིན་[vb]ནོ།[sp]

The NN dot is used BETWEEN the items in a list, not after the list as a whole. The list as a whole is a unit in Tibetan. It is a noun phrase and is “glued” together.

Since the example sentence ends in a linking verb, it has three main parts:

- subject: three nouns in a list, སེམས་ཡིད་རྣམ་པར་ཤེས་པ་

- complement: “equivalent”, དོན་གཅིག་

- verb: ཡིན་

¶ Lexical Particles – Final Syllables

There are five types of final syllables (using the term narrowly, not just describing any syllable that ends a word). These particles are found only in nouns, adjectives, and a few pronouns.

- generic suffix syllables (པ་ པོ་ བ་ བོ་ མ་ མོ་)

- subjective suffix syllables (པ་ པོ་ བ་ བོ་ ཅན་ མཁན་)

- restrictive suffix syllables (ཙམ་ and ཉིད་)

- possessive suffixes (དང་བཅས་པ་ and དང་ལྡན་པ་)

- separative suffixes (དང་བྲལ་བ་)

Generic suffix syllables are discussed below. Subjective and restrictive suffix syllables will be discussed in Chapter 11.

¶ Generic Suffix Syllables

Nouns or adjectives ending in པ་, པོ་, བ་, བོ་, མ་, and མོ་ are examples of generic suffix syllables. In some, but not all, cases, these syllables have been placed after verbs (as true nominalizing syllables) to create nouns and adjectives.

Here are a few examples of nouns with no obvious relation to a verb:

རྣམ་པ་ aspect, type

དཀར་པོ་ white

རྩ་བ་ root

ཆུ་བོ་ river

Here are some examples of nouns created from verbs:

ཡོད་པ་ existent, existence

རྒྱལ་པོ་ king

རྒྱལ་མོ་ queen

སྐྱེ་པོ་ being, person

སྲུང་མ་ guardian, protector

བ་ and པ་ are by far the most common concluding syllable.

¶ Feminine Nouns, Gender, and Title Abbreviation

ཆེན་མོ་ and རྒྱལ་མོ་ are feminine words, insofar as any Tibetan words may be said to have gender. The genderless form of ཆེན་མོ་ is ཆེན་པོ་, as seen in ཐེག་པ་ཆེན་པོ་ (Mahāyāna or Great Vehicle).

Nouns in languages such as Sanskrit, Latin, Spanish, and French are either feminine, masculing, or neuter, and in these languages adjectives must agree in gender with nouns. Tibetan is ambiguous both as to number and gender, except in certain instances when the feminine is specified through the use of the final syllables མ་ and མོ་.

It is NOT the case that any word ending with མ་ and མོ་ should be understood as feminine. For example, the very common adjectives ཟབ་པོ་ and ཕྲ་མོ་ are used without reference to gender, as are དབུ་མ་ and སྲུང་མ་

Most names in Tibetan are can be used be males are females. There are a few, however, specifically female names.

སྒྲོལ་མ་ Tara

རྡོ་རྗེ་རྣལ་འབྱོར་མ་ Vajrayogini [a female Buddha]

རྣལ་འབྱོར་མ་ yogini (a woman who is a meditator, as opposed to རྣལ་འབྱོར་པ་, yogi)

Books are often given feminine titles, especially in the case of abbreviated titles.

ལམ་རིམ་ཆེན་མོ་ Great Stages of the Path

ལམ་རིམ་ཆེན་མོ་ means great [exposition of the] stages of the path [to enlightenment]. ལམ་ means path. རིམ་ is an abbreviated form of རིམ་པ་ which means stage. This is the abbreviated title of Tsong-ha-pa's famous systematic presentation of Buddhist practice from the viewpoint of texts of Indian and Tibetan Buddhism.

Liturgical texts are sometimes known by abbreviated feminine titles based on their first few words. For example:

དམིགས་མེད་བརྩེ་བའི་གཏེར་ཆེན་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས།

Avalokiteshvara, a great repository of compassion [that] does not objectify

Is abbreviated:

དམིགས་བརྩེ་མ་

non-objectifying compassion

Non-objectifying compassion is compassion that does not take inherently existing sentient beings as its object, but rather sees only beings empty of inherent existence, and thus as dependent arisings. The non-objectified is emptiness--that is, reality.

¶ Migtsema - དམིགས་བརྩེ་མ་

དམིགས་མེད་བརྩེ་བའི་གཏེར་ཆེན་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས། །

དྲི་མེད་མཁྱེན་པའི་དབང་པོ་འཇམ་དཔལ་དབྱངས། །

བདུད་དཔུང་མ་ལུས་འཇོམས་མཛད་གསང་བའི་བདག །

གངས་ཅན་མཁས་པའི་གཙུག་རྒྱན་ཙོང་ཁ་པ། །

བློ་བཟང་གྲགས་པའི་ཞབས་ལ་གསོལ་བ་འདེབས། །

Avalokiteshvara, great treasure of non-objectifying compassion;

Manjushri, master of stainless wisdom, lord of Secrets, destroyer of the entire host of maras;

Tsongkhapa, crown ornament of the sages of the Land of Snow:

Losang Dragpa, at your feet I make requests.

¶ Pluralizing Suffix Syllables

རྣམས་ དག་ ཅག་ ཚོ་

Remember that Tibetan words do not specify number. བུམ་པ་ is ambiguous as to if it means pot or pots. Because of this, adjectives and suffix syllables are frequently added to specify number. These additions are not part of the noun itself and will not be in the dictionary. For example, བུམ་པ་རྣམས་ explicitly means pots. However, བུམ་པ་རྣམས་ is not in the dictionary, only བུམ་པ་. Because these suffix syllables do not form part of the basic noun, pronoun, or adjective, they are also known as optional suffix syllables.

The pluralizing suffix syllables are: རྣམས་ དག་ ཅག་ ཚོ་

དེ་ means that or those (is ambiguous as to number). དེ་རྣམས་ and དེ་དག་ just mean those (are explicitly plural).

These particles are included among lexical particles (as opposed to syntactic particles) because the plural nouns, pronouns, and adjectives they are used to create may then be marked with case marking particles or followed by syntactic particles, like any other nouns, pronouns, and adjectives.

Pluralizing particles are found after nouns, pronouns, and adjectives. In most cases, in noun phrases, they are only found at the end and terminate the noun phrase. བུམ་པ་དམར་པོ་རྣམས་ – red pots. The noun-adjective phrase བུམ་པ་དམར་པོ་ functions as a unit, which is then pluralized with རྣམས་.

¶ Negative Particles

མ་, མི་ → before word (negative prefix syllables)

མིན་, མེད་ → after word (negative suffix syllables)

མིན་ and མེད་ are, in fact, verbs. མིན་ is the linking verb is not. མེད་ is the negative verb of existence does not exist. They have been categorized here as negative suffix syllables following tradition, but technically they can be understood as verbal nouns and adjectives, not lexical particles. They are often found as part of a word, as in the following examples.

སྐྱབས་མེད་ without refuge, protectorless

བདག་མེད་ selfless, selflessness

གཉིས་མིན་ non-dual, non-duality

¶ Negative Prefix Syllables

མ་, མི་ are used before verbs, negating their meaning.

ཡིན་ is → མ་ཡིན་ is not

སྐྱེ་ born → མི་སྐྱེ་ not born

In the case of compound verbs and verbs with prefix particles, such as རྣམ་པར་རྟོག་ (conceptual, conceptualize, think), the negating particle is placed in front of the core verb (རྟོག). This produces a new word: རྣམ་པར་མི་རྟོག་ (non-conceptual).

Negating particles can be used with nouns as well as verbs.

དགེ་བ་ → མི་དགེ་བ་

wholesome, virtuous → non-virtuous, unwholesome

རྟག་པ་ → མི་རྟག་པ་

permanent → impermanent