¶ Chapter 9 – Words – Parts of Speech

¶ Introduction and Review

At the most general level, one can say that any written symbol on a Tibetan page is one of the following four:

- word (ཤེས་ or ཤེས་པ་)

- a case marking particle (ལ་ གྱི་ ཀྱིས་)

- a syntactic particle (དང་ ཀྱང་)

- a punctionation mark (such as the ཚེག་ and the ཤད་)

Both particles and words are made of syllables. There are three types of particles:

- case marking particles,

- syntactic particles, and

- lexical particles.

Lexical particles are a special case because they do not appear outside of words. They are a class of a special type of syllables that frequently appear within words. There are five types of lexical particles (this is treated in depth in Chapter 10 of Wilson).

- prefix particles (རྣམ་པར་ in རྣམ་པར་ཤེས་པ་)

- negative prefix particles (མ་ in མ་ཡིན་)

- final syllables (པ་ in བུམ་པ་)

- optional suffix syllables (དག་ and རྣམས་ when used as puralizing suffixes)

- negative verbal particles (མེད་པ་ in རྟོགས་པ་མེད་པ་)

In contrast to lexical particles, syntactic and case marking particles operate at the level of words (not within them) to create phrases, clauses, and sentences.

Letters and syllables (some of which are lexical particles) generate the phonemic dimension, whereas words and particles operate in the lexical dimension, and, when they are put together, in the syntactic dimension. The syntactic dimension is expressed in the construction of phrases, clauses, and sentences from words and particles.

There are six categories of words:

- nouns

- pronouns

- adjectives

- verbs

- adverbs

- postpositions

མངོན་པར་རྫོགས་པར་སངས་རྒྱས་པ་ complete, perfect enlightenment

མངོན་པར་ complete

རྫོགས་པར་ perfect

¶ Syntactic and Case Marking Particles

Tibetan uses case marking particles attached to the ends of words (nouns, noun phrases, and verbals) to connect the words to the rest of the sentence. Case marking particles (along with verbs) are what give the sentence its structure. In English, this is primarily signified by word order and prepositions, such as to, at, from, and so on.

Notice that they are prepositions--they precede the word or phrase they are connecting to the larger sentence. For example: She went to the store. And: He got sick in India.

In Tibetan, this order is reversed. In fact, you'll find that Tibetan is surprisingly consistently back-to-front compared to English. In “Tenglish” those two sentences might read like the following, with “to” and “in” being replaced by case marking particles in Tibetan.

SHE STORE-TO WENT

HE INDIA-IN BECAME SICK

Tibetan uses postpositions instead of prepositions.

In the sentences above, if they were translated into Tibetan, both the “to” and the “in” would be signified by the same group of particles, the la-group, and might end up looking like the following.

SHE STORE-ལ་ WENT

HE INDIA-ལ་ BECAME SICK

This makes it all seem very systematic. Unfortunately, as you'll discover, particles come in groups and each group has multiple, unrelated usages, such that it takes a little study and practice to really get a sense of how they work.

While all case marking particles and syntactic particles are technically postpositions, when we talk about “postpositions” in Tibetan grammar in this system, we are generally referring to a specific subset of particles that are often used to confer meaning like relative location (in front of or on top of).

Some postpositions (in both senses of the word):

མདུན་ front

རྒྱབ་ back, rear

སྟེང་ top

ཁུལ་མ་ bottom or side

The key point is that while in English the sentence structure is determined largely by word order and prepositions, in Tibetan the sentence structure is mostly determined by postpositions (case marking particles and syntactic particles following the words they modify). In Tibetan, word order is not nearly as significant in many cases. There are, however, cases where word order is very significant. For example, the subject and complement of a linking verb. There are also general guidelines about word order. Such as: generally speaking the subject or agent of a verb will be the first thing to appear in a sentence, but not always, and they are often--maddeningly--simply omitted.

In fact, many things are frequently omitted in Tibetan, probably because they had to memorize all this and carve it into wood blocks, and this combined with the strange usage of the same groups of particles to convey vastly different meanings, makes reading Tibetan either fun or horribly difficult, or both, in turns, depending on one's mood and the availability of a Geshe or a native speaker.

¶ Declensions & Case Marking Particles

The first time I heard the word “declension” I literally asked, “What the hell is a declension?”

A declension is grammatical term that refers to modifying a noun, pronoun, or adjective to show its use in a sentence.

In Tibetan, nouns and noun phrases are declined through the addition of case marking particles, such as ལ་, འི་, ཀྱིས་, དུ་, and ནས་.

Nouns (and pronouns, adjectives, and verbals) are declined, that is to say, marked with case marking particles. Verbs are not declined (except for verbals, which are really verbs operating as nouns and adjectives), and thus verbs are not marked with case marking particles.

However, confusingly, the same particles that are used as case marking particles are used as conjunctive and disjunctive syntactic particles that can follow verbs. For example, གི་, གྱི་, and ཀྱི་ are mostly seen as the sixth-case marking particles. When used in this way, they never follow verbs (although they often follow verbals). But, གི་, གྱི་, and ཀྱི་ can be used after a verb as a disjunctive syntactic particle, meaning something like “but” or “although.”

In fact, most case marking particles have non-case usages. The function is determined by context and verb type.

Traditionally there are eight different cases in Tibetan. Six of the cases are marked by particles, two are not marked by particles. Of the six that are marked by particles, unfortunately, as you'll see, three of the cases are marked BY THE SAME group of particles.

When a noun or noun phrase is not marked with a case marking particle, it is in the nominative case. The absence of a case marking particle often tells us as much about the function of the words in the sentence as a case marking particle would. What this actually means is determined by the verb type. Some verbs have subjects in the nominative. Other verbs have objects in the nominative.

The verbs together with the case marking particles determine the structure of the sentence and the context for the words. It's easy to slip into thinking that the verb determines the grammar or the case marking particles determine the grammar, but in reality the grammar arises dependently on the context of the case marking particles and the verb type.

Some basic examples of case marking particles and their approximate translations:

བུམ་པའི་ POT-OF (of the pot, pot’s)

བུམ་པའི་ཁ་དོག་ POT-OF-COLOR (the color of a pot)

བུམ་པ་ལ་ POT-IN (in the pot, at the pot, for the pot)

བུམ་པ་ལས་ POT-FROM (from the pot, from among the pots)

¶ Words

In Wilson, the term word is used in distinction to particles. Particles in Tibetan are used to do things like mark cases and indicate sequence or conjunction. Particles in and of themselves have no lexical meaning (think “a” or “the” or “and"). They are structural. Words, as the term is used here, includes everything in Tibetan that is not a particle. Words signify meaning. They include nouns, pronouns, adjectives, adverbs, and verbs.

In English, words tend often to be multisyllabic and our “particles” (prepositions, interjections, conjunctions, etc…) are often one to two syllables. Tibetan is a heavily monosyllabic language. Many of the words are single syllables. As such, at first it may not be as easy to distinguish particles from words. There are, fortunately, a finite number of particles, and however confusing their overlapping usages can be, a diligent student does eventually get a grasp on them.

Words are comprised of one or more syllables and have their own independent lexical meaning. However, since there are many single-syllable words, it is common for single syllables to have ideas associated with them.

Words are formed, not just through the combination of syllables, but also through the combination of other words. Take a look the examples below.

ཀུན་ཏུ་བཟང་པོ་ Samantabhadra

ཀུན་ཏུ་ thoroughly

བཟང་པོ་ good

མར་མེ་ butter lamp

མར་ butter

མེ་ lamp

¶ Six Functions of a Tibetan Word

A Tibetan word can perform one of six basic syntactic functions (with the exception of verbals).

1. noun

2. verb

3. pronoun

4. adjective

5. adverb

6. postposition (case marking or syntactic particle)

A Tibetan word is either a noun, verb, pronoun, adjective, adverb, or postposition. Any given word can play only one role in a phrase, clause, or sentence. Except for verbals, which often act as both nouns and verbs.

For example, བུམ་པ་is always a noun. It is never a pronoun, adjective, adverb, or verb. Similarly the word ཡིན་ is a verb; it can be made into a noun with a final པ་, but as ཡིན་ it is a verb.

Verbals are dealt with in great detail later, but they are in essence nominalized verbs. Think “realization” from “to realize" or “existence” from “to exist.” They are an exception to this rule because in Tibetan, when a verb is nominalized, they can still act as a verb to their left in the sentence, with their own grammar, while acting as a noun or adjective to their right. This is vitally important to the construction of Tibetan sentences because technically a Tibetan sentence can only have one verb and must end with that verb. Verbals allow Tibetan sentences to contain far more complexity than this rule would seem to allow.

¶ Verbs

Verbs are the heart of a Tibetan sentence or clause. They always occur at its end.

Verbs end sentences or clauses, with their subjects and objects before them, never after them.

A sentence is defined by the fact that a verb ends it.

A Tibetan sentence is a series of words that completely expresses a thought, ends a verb, and is not itself a part of a clause or sentence.

The most basic verb forms look like ཡིན་ (is) and བྱེད་ (do, make, perform). Generally they do not end in པ་ or བ་. Verbal nouns and verbal adjectives (or participles), collectively known as verbals, on the other hand, usually do end in པ་ or བ་. The པ་ or བ་ is often omitted however, particularly in verse.

The simplest verbs are existential verbs: ཡིན་ (is) and ཡོད་ (exist)

They indicate no action. Instead they mean that something is something (ཡིན་) or that something exists (ཡོད་). Note that in Tibetan “to be something” and “to exist” are different verbs whereas in English both are expressed by “is/are/am.”

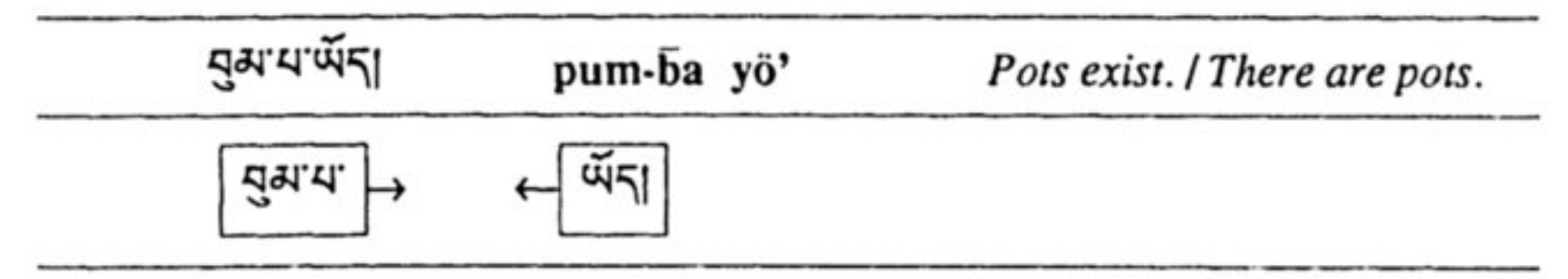

SUBJECT → ← VERB

བུམ་པ་ → ← ཡོད། Pots exist. There are pots. There is a pot.

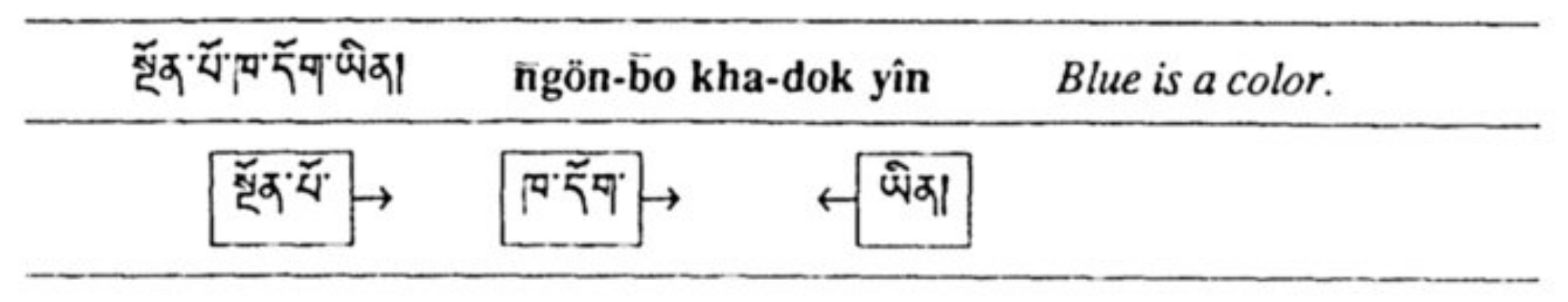

SUBJECT → COMPLEMENT OR OBJECT → ← VERB

སྔོན་པོ་ → ཁ་དོག་ → ← ཡིན། Blue is a color.

The basic minimal arrangement of words in a Tibetan sentence or clause is:

SUBJECT → ← VERB

This following pattern is more common:

SUBJECT → COMPLEMENT OR OBJECT OR QUALIFIER → ← VERB

¶ Three Main Categories of Verbs

It is helpful to categorize verbs in terms of the syntax they require in the sentences they end. Or, to look at this another way, to categorize them on the basis of the case marking particles that are used to mark their subjects, objects, compliments, and qualifiers.

There are three main categories of verbs in Tibetan:

1. Nominative (subject in first case)

2. Agentive (subjects in third/agentive case)

3. Specialized (subjects in the seventh/locative or fourth/purposive-beneficial cases)

The third category (with a significant exception), comprises verbs that are in most other instances either agentive or nominative verbs. In certain uses their subjects are locative or purposive.

The exception is དགོས་ (need, require), the verb of necessity. See Chapter 14, along with the specialized use of ཡོད་ (normally nominative) as a verb of possession.

In the first example below, the subject, sound (སྒྲ་), is in the nominative case. That is, it is unmarked. It is marked by the absence of a case marking particle. The compliment, impermanent (མི་རྟག་པ་), is also in the nominative case.

¶ Nominative Subject

སྒྲ་མི་རྟག་པ་ཡིན།

SOUND IMPERMANENT IS

Sound is impermanent.

The next example is an agentive verb construction. The verb བསྟན་ is an agentive verb whose agent is marked with a third case marking particle ཀྱིས་. Notice that the case marking particle is not translated.

¶ Agentive Subject

སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་ཆོས་བསྟན།

BUDDHA DOCTRINE TAUGHT

Buddha taught the doctrine.

This final introductory paradigm shows how a normally nominative verb of existence, མེད (to not exist), is used with a locative subject to show possession (or lack of possession, in this case). Arhats (དགྲ་བཅོམ་) is marked with a la-group particle ལ, which marks the word as the subject.

¶ Locative Subject

དགྲ་བཅོམ་པ་ལ་ཉོན་མོངས་མེད།

ARHATS AFFLICTIONS NOT-HAVE

Arhats do not have afflictions.

I'll also point out that, although this is translated as “arhats" in the plural, the word is not explicitly pluralized and is being translated as plural simply because of meaning and context. Saying “arhat does not have afflictions" just doesn't make any sense, nor is it what the Tibetan intends.

Note that མེད is explicitly negative: to not exist or to not have. The positive form is ཡོད་: to exist or to have.

¶ Verb Forms

Verb types may broadly be subsumed under two types:

1. Final (or terminal)

2. Open

Final forms close sentences. They range from simple basic forms (ཤེས་, བྱེད་) to lengthy verb phrases (མངོན་པར་རྫོགས་པར་སངས་རྒྱས་པར་འགྱུར་).

Final forms include:

- basic verbs (such as ཤེས་, know)

- compound verb phrases (such as ཤེས་ནུས་, able to know)

- phrases composed of verbs and auxiliary verbs (such as ཤེས་པར་བྱ་, one should know), of which there are two main types:

- collocations or phrasal verbs

- infinitive verbs plus auxiliary verbs

Open verbs do not end sentences, but either (1) act to end clauses within sentences or (2) function within verb phrases. Clauses are like small sentences that function within a larger sentence.

Open verb forms include:

1. Some clauses end in basic verb forms (like ཡིན་) followed by a syntactic particle, such as ན་ (if or when) or the continuative particle ནས་. This indicates that the sentence continues past the verb (and the clause it terminates). The following clause means given that pots are impermanent or if pots are impermanent– བུམ་པ་མི་རྟག་པ་ཡིན་ན་

2. Many clauses end in verbs made into nouns. Verbal nouns and adjectives--aka, verbals. Verbals are another very important way that Tibetan language builds complex sentences. It will be covered in Chapter 10. Where སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་ཆོས་བསྟན་ is a sentence that means Buddha taught the doctrine, the following clause is a verbal clause (ending in the verbal བསྟན་པ་) that means taught by the Buddha, སངས་གྱས་ཀྱིས་བསྟན་པ་

The internal parts of verb phrases are often open verbs. For example, ཤེས་པར་ in the verb phrase ཤེས་པར་བྱ་ is an example of an open construction. ཤེས་པར་ by itself is incomplete and cannot end a sentence. བྱ་ is a terminal verb, however, and can end a sentence.

Don't forget that verbs, particularly ཡིན་, can be omitted. A sentence may end in a terminal ཡིན་ that is not, in fact, there.

Unlike verbs in most other languages, literary Tibetan verb forms do not vary according to person. And while verbs can have up to four tenses: past, present, future, and imperative, many verbs only have one or two of these forms actually distinguished by spelling. This is not true of colloquial Tibetan, which does modify verbs according to person and tense far more regularly than classical Tibetan.

¶ Nouns, Pronouns, and Adjectives

Many nouns are verbs formed into nouns. These are verbal nouns. They are formed simply by adding པ་ or བ་ to the end of the core verb.

- ཡོད་ (to exist) → ཡོད་པ་ (existence, existent)

- ཡིན་ (is) → ཡིན་པ་ (being, occurrence)

- ཤེས་ (know) → ཤེས་པ་ (knowledge, known)

- བྱེད་ (do, make) → བྱེད་པ་ (action, agent)

- འགྲོ་ (go) → འགྲོ་བ་ (going, migration, migrator)

The last word འགྲོ་བ་ is a common word that means literally go-er. It is the common word for a person in cyclic existence, someone going from one lifetime to antoher. འགྲོ་བ་ in that case then translates literally either as migrator or migration, depending on whether the text is speaking of a person or a potential state of rebirth.

Other nouns are just nouns, not derived from verbs.

- བུམ་པ་ (pot)

- མི་ (person)

- བོད་ (Tibet)

Note that there are no capitol letters in Tibetan to set off proper nouns. In fact, names are frequently pseudo-descriptive phrases containing words such as “gentle voiced" or “ocean of wisdom," and as such, until one learns to spot the common names, it can be very confusing when one tries to start parsing the grammar of the sentence with a few seemingly random, ungrammatical words thrown in.

Most nouns have both a normal and an honorific form. The honorific form is used when speaking about a venerated person, such as a teacher, parent, or Buddha. It is never used in the first person.

ལུས་ སྐུ་ body

ངག་ གསུང་ speech

ཡིད་ ཐུགས་ mind

Thus a Buddha’s mind is ཐུགས་, not ཡིད་ or སེམས་

And a Buddha’s compassion is ཐུགས་རྗེ, not སྙིང་རྗེ་

It is also very important to remember that the basic Tibetan noun is neither singular or plural. Sometimes the text will include explicit pluralizers, such as རྣམས་, but not necessarily. If one does not see this, one cannot assume that the noun is either singular or plural, but it should be obvious from context which it is.

¶ Pronouns

Pronouns are words that take the place of nouns. There are personal pronouns such as ང་, or I. There are relative pronouns such as གང་ (which, who, whom, that which, or he/she who) and སུ་ (who, whom). Both of these are also used as interrogative pronouns (what, which, who).

Personal pronouns vary according to person. ང་ is the first person pronoun. ཁྱོད་ is the second person pronoun. Like nouns, pronouns occur in ordinary-honorific pairs.

The most common pronouns are དེ་ (that) and འདི་ (this). Similar to their English counterparts, they are adjectives which, when used alone (when they are not modifying a noun), function as pronouns. དེ་ means that, but also means he/she/it. དེ་དག་ means these and also they.

Here's an example sentence with a pronoun:

དེ་མི་རྟག་པ་ཡིན་

That is impermanent.

Some important pronouns:

ང་ I

ཁྱོད་ you

སུ་ who, whom

གང་ which, who, whom, that which, or he/she who

དེ་ that, also he/she/it

འདི་ this

དེ་དག་ those (or they)

དེ་རྣམས་ those (or they)

དེ་ is ambiguous with regards to plurality and can be singular or plural.

Unlike the verbs in many other languages, Tibetan verbs in CLASSICAL Tibetan do not vary according to person. First, second, and third person are all the same. This is not true in colloquial Tibetan, where verb do change according to person.

ང་སེམས་ཅན་ཡིན།

I am a sentient being.

དེ་སེམས་ཅན་ཡིན།

He/she is a sentient being.

དེ་དག་སེམས་ཅན་ཡིན།

They are sentient beings.

¶ Adjectives

Adjectives modify nouns. Most commonly they follow the noun they modify, creating a noun-adjective phrase.

བུམ་པ་དམར་པོ་ red pot

སེམས་ཅན་ཀུན་ all sentient beings

མི་བདུན་ seven humans

Some adjectives, however, typically precede the nouns they modify, connecting to them using the sixth-case. These are adjective-noun phrases.

དགེ་བའི་སེམས་ virtuous mind

དམ་པའི་ཆོས་ excellent doctrine, true doctrine, holy doctrine

Remember that བའི་ is pronounced “way” and པའི་ is pronounced “bay”

Since noun phrases (adjectives combined with nouns) are themselves nouns, they can be modified by an adjective.

བུམ་པ་དམར་པོ་དེ་ that red pot

དགེ་བའི་ཆོས་ཀུན་ all virtuous phenomena

¶ Adverbs

Adverbs are words that modify either verbs or adjectives. That do not exist as a separate category in traditional Tibetan grammar.

ཇི་ལྟར་ how [like-what]

དེ་ལྟར་ in that way [like that]

ཅུང་ཟད་ a little

དེ་བཞིན་དུ་ thus

There are two types of Tibetan adverbs:

1. words that are always adverbs

2. words that are themselves nouns or adjectives, but are modified to use as adverbs

འབའ་ཞིག་ is an adjective meaning only. འབའ་ཞིག་ཏུ་ also means only, but now modifies verbs and verbals. Note the addition of the ཏུ་ to འབའ་ཞིག་ that turns it into an adverb.

Some examples of adverbs that are nouns or adjectives modified to use as adverbs:

འབའ་ཞིག་ only འབའ་ཞིག་ཏུ་ only

སྐད་ཅིག་མ་ momentary སྐད་ཅིག་མར་ moment by moment

རྫོགས་པ་ completion ཛོགས་པར་ completely

རྟག་པ་ permanent རྟག་པར་ permanent, always

གཙོ་བོ་ main, chief གཙོ་བོར་ predominantly

¶ Postpositions

Postpositions are so-called because they occur after the word they relate to the rest of the phrase, clause, or sentence. This category is something of a grab-bag. Many postpositions are in fact more like syntactic particles. However, syntactic particles cannot be declined, and postpositions are—that is, they are typically marked by case marking particles.

Postpositions are connected to the word or phrase that precedes them with a connective case particle.

They commonly indicate relations of

- time,

- place, or

- purpose.

Some examples include:

མདུན་ front

སྟེང་ top

རྗེས་ after

ཆེད་ purpose

In the following examples, དེ་ is used as a pronoun. དེ་ is connected to a postposition using ཡི་, the sixth case connective.

དེ་ཡི་མདུན་ལ་ in front of that

དེ་ཡི་སྟེང་དུ་ on top of that

དེ་ཡི་རྗེས་སུ་ after that

དེ་ཡི་ཆོད་དུ་ for the sake of that

Two more examples:

རང་གི་མདུན་དུ་ in front of one

མི་རྟག་པ་ཡིན་པའི་ཕྱིར། because of being impermanent

ཕྱིར་ is an important postpositional that is used frequently in Tibetan logic. It is notable because it breaks the rule of a verb ending a sentence.

¶ Numbers and Numerals

Above ten, the names of Tibetan numbers are formed in a regular way. From ten to nineteen, they are merely a reflection of the numeral – the first syllable is བཅུ་ (ten) and the second, whatever number is added to ten to make the number in question. The first three are illustrative of the names for the numbers through nineteen:

10 ༡༠་ བཅུ་

11 ༡༡ བཅུ་གཅིག་

12 ༡༢་ བཅུ་གཉིས་

13 ༡༣ བཅུ་གསུམ་

Twenty through twenty-nine follow the same model, with two modifications: the word for twenty is ཉི་ཤུ་ (not གཉིས་བཅུ་). There is an intermediate connecting syllable.

20 ༢༠་ ཉི་ཤུ་

22 ༢༡་ ཉི་ཤུ་ཉེར་གཅིག་ or ཉི་ཤུ་རྩ་གཅིག་

23 ༢༢་ ཉི་ཤུ་ཉེར་གཉིས་ or ཉི་ཤུ་རྩ་གཉིས་

As shown above, there are two ways of naming the numbers from twenty-one through twenty-nine. ཉི་ཤུ་ཉེར་གཉིས་ may be abbreviated to ཉེར་གཉིས་.

The numbers for thirty to thirty nine are as follows.

30 ༣༠་ སུམ་ཅུ་

31 ༣༡་ སུམ་ཅུ་སོ་གཅིག or སུམ་ཅུ་རྩ་གཅིག

The intermediate syllable རྩ་ may be used in numbers from twenty-one through ninety-nine, although in numbers above thirty it is more common to see a different intermediate syllable for every set of ten. The remaining numbers are formed in accordance with the following model:

40 ༤༠་ བཞི་བཅུ་

41 ༤༡་ བཞི་བཅུ་ཞེ་གཅིག་

50 ༥༠་ ལྔ་བཅུ་

51 ༥༡་ ལྔ་བཅུ་ང་གཅིག་

60 ༦༠་ དྲུག་བཅུ་

61 ༦༡་ དྲུག་བཅུ་རེ་གཅིག་

70 ༧༠་ བདུན་ཅུ་

71 ༧༡་ བདུན་ཅུ་དོན་གཅིག་

80 ༨༠་ བརྒྱད་ཅུ་

81 ༨༡་ བརྒྱད་ཅུ་གྱ་གཅིག་

90 ༩༠་ དགུ་བཅུ་

91 ༩༡་ དགུ་བཅུ་གོ་གཅིག་

100 བརྒྱ་

1000 སྟོང་

Set of 100 བརྒྱ་ཕྲག་

Set of 1000 སྟོང་ཕྲག

Hundreds་and thousands are counted the same way as tens:

100 ༡༠༠་ བརྒྱ་

101 ༡༠༡་ བརྒྱ་དང་གཅིག་

102 ༡༠༢་ བརྒྱ་དང་གསུམ་

200 ༡༠༡་ ཉིས་བརྒྱ་

300 ༡༠༢་ སུམ་བརྒྱ་

1000 ༡༠༠་ སྟོང་

2000 ༡༠༡་ ཉིས་སྟོང་

3000 ༡༠༢་ སུམ་སྟོང་

Alternately, hundreds and thousands may be counted using ཕྲག:

100 ༡༠༠་ བརྒྱ་

200 ༡༠༡་ བརྒྱ་ཕྲག་གཅིག་

300 ༡༠༢་ བརྒྱ་ཕྲག་གཉིས་

1000 ༡༠༠་ སྟོང་

2000 ༡༠༡་ སྟོང་ཕྲག་གཅི

3000 ༡༠༢་ སྟོང་ཕྲག་གཉིས་

Larger numbers:

10,000 ཁྲི་

100,000 འབུམ་

1,000,000 ས་ཡ་

10,000,000 བྱེ་བ་

Numbers are frequently used as adjectives. Here are some examples.

སྒྲོལ་མ་ཉེར་གཅིག་

twenty-one Taras

གནས་བརྟན་བཅུ་དྲུག་

the sixteen Sthaviras

ཡི་གེ་བརྒྱ་

one hundred syllables

ཡི་གེ་བརྒྱ་པ་

that having one hundred syllables

The པ་ above is an example of a subjective suffix syllable. Where ཡི་གེ་བརྒྱ་ means 100 syllables, ཡི་གེ་བརྒྱ་པ་ means that having 100 syllables or that which has 100 syllables.

འབུམ་ལྔ་

five [sets of] one hundred thousand

འབུམ་ is used both literally, as above, and figuratively as a metphor for a great number of things. In the first example below, འབུམ་ is used as a syllable within a word, in the second, it is used metaphorically.

གསུང་འབུམ་ collected works [hundred thousand proclomations]

སྐུ་འབུམ་ Gum-bum Monastery [hundred thousand images[