Chapter 12

Declension

Nominative and Connective Case Paradigms

Classes of Nominative Verbs

Linking Verbs

Types of Enlightenment

¶ The Eight Cases

Case marking particles are placed after nouns, pronouns, adjectives, and postpositions to show how they are connected to words that come after them. Modifying words, phrases, and clauses to show their relationship to other parts of a phrase, clause, or sentence is called a declension.

Case particles make no sense by themselves. Their meaning is entirely relational, indicating the relationship between words in a phrase, clause, or sentence.

Tibetan grammar models it on Sanskrit, in which there are eight cases.

| Case Number | Case Name | Case Marking Particle | Latin Name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | first case | nominative | no particle | nominative |

| 2 | second case | objective | སུ་, རུ་, ཏུ་, དུ་, ན་, ར་, ལ་ | accusative |

| 3 | third case | agentive | གིས་, ཀྱིས, ་གྱིས, ་འིས, ་ཡིས་ | instrumental |

| 4 | fourth case | beneficial-purposive | སུ་, རུ་, ཏུ་, དུ་, ན་, ར་, ལ་ | dative |

| 5 | fifth case | originative | ནས, ལས་ | ablative |

| 6 | sixth case | connective | གི, ཀྱི་, གྱི, འི, ཡི་ | genitive |

| 7 | seventh case | locative | སུ་, རུ་, ཏུ་, དུ་, ན་, ར་, ལ་ | locative |

| 8 | eight case | vocative | no particle | vocative |

Following the lead of western Sanskritists, many scholars use the Latin grammatical terms for Tibetan declensions. Some of these have been retained here, but only when they adequately translate the Tibetan term. Regardless, cases are more frequently identified by their numbers: first case or second case (as opposed to nominative or objective). Both names and numbers are all used, however, and must be learned.

The last column in the table above lists the Latin names of the case endings derived from Sanskrit. Wilson and the Hopkins system in general does not use these, but you might see them in other places. There is no need to memorize them.

Notice that the 2nd, 4th, and 7th cases all share the same seven case marking particles (སུ་, རུ་, ཏུ་, དུ་, ན་, ར་, ལ་). That's not a mistake. Or maybe it is a mistake, but it's a mistake that was made thousands of years ago.

Two particles are listed by grammarians as particles denoting the eight case: ཀྱེ་ and ཀྭ་ཡེ་. However, unlike the other case particles, they occur before the word and not after it. In English, they would be interjections and they are so called here.

There are rules based on sound and spelling to determine which particles follow which words. This will be presented later.

Here are the cases in Tibetan.

| 1 | རྣམ་དབྱེ་དང་པོ་ | nominative | ངོ་བོ་ཙམ་བརྗོད་པ་ |

| 2 | རྣམ་དབྱེ་གཉིས་པ་ | objective | ལས་སུ་བྱ་བའི་སྒྲ་ |

| 3 | རྣམ་དབྱེ་གསུམ་པ་ | agentive | བྱེད་སྒྲ་ |

| 4 | རྣམ་དབྱེ་བཞི་པ་ | beneficial-purposive | དགོས་ཆེད་ཀྱི་སྒྲ་ |

| 5 | རྣམ་དབྱེ་ལྔ་པ་ | originative | འབྱུང་ཁུངས་ཀྱི་སྒྲ་ |

| 6 | རྣམ་དབྱེ་དྲུག་པ་ | connective | འབྲེལ་སྒྲ་ |

| 7 | རྣམ་དབྱེ་བདུན་པ་ | locative | རྟེན་གནས་ཀྱི་སྒྲ་ |

| 8 | རྣམ་དབྱེ་བརྒྱད་པ་ | vocative | བོད་སྒྲ་ |

Appendix 5 of Wilson goes into great detail about the usage of each case.

¶ Nominative Case Paradigms

The nominative case is distinguished by the lack of a case marking particle. However, this does not mean that all words without a case marking particle are nominatives. For example, when analyzing noun phrases, such as nouns in a list or noun-adjective, the individual nouns in these phrases are not nominative, only the list as a whole is in the nominative.

The most basic uses of the nominative are as the subject or complement of sentences or clauses ending in linking verbs.

Recall that there are three types of verbs in Tibetan (in the broadest classification):

- Nominative (subject in the nominative case)

- Agentive (agent in the third case)

- Specialized (subject in the fourth or seventh cases)

Here we are talking about the first category above. Verbs that have their subject in the first or nominative case.

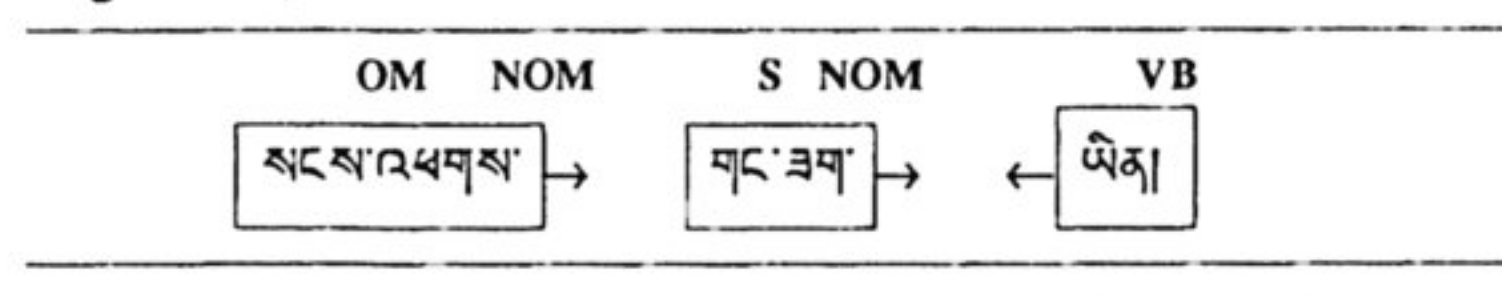

¶ Linking Verbs

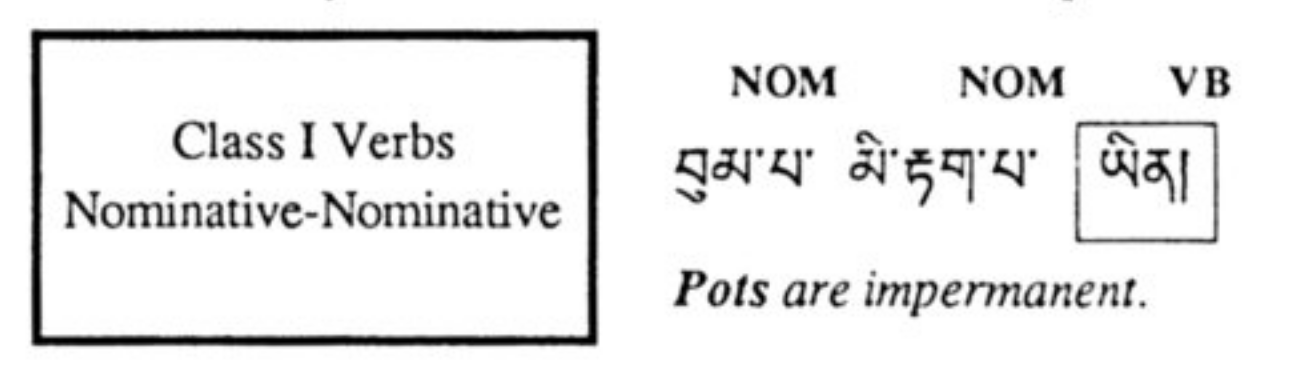

Linking verbs are the most basic use of nominative verbs. Both the subject and the complement of a linking verb are in the nominative case. The basic form of a linking verb is “A B IS" (for A is B). Be careful! “is” in English is a loose term. It operates both for linking and for existence. Further, remember that just because “A B IS” (A IS B) does not mean that “B A IS" (B A IS). Just because “pots are impermanent” does not mean that “impermanent are pots.”

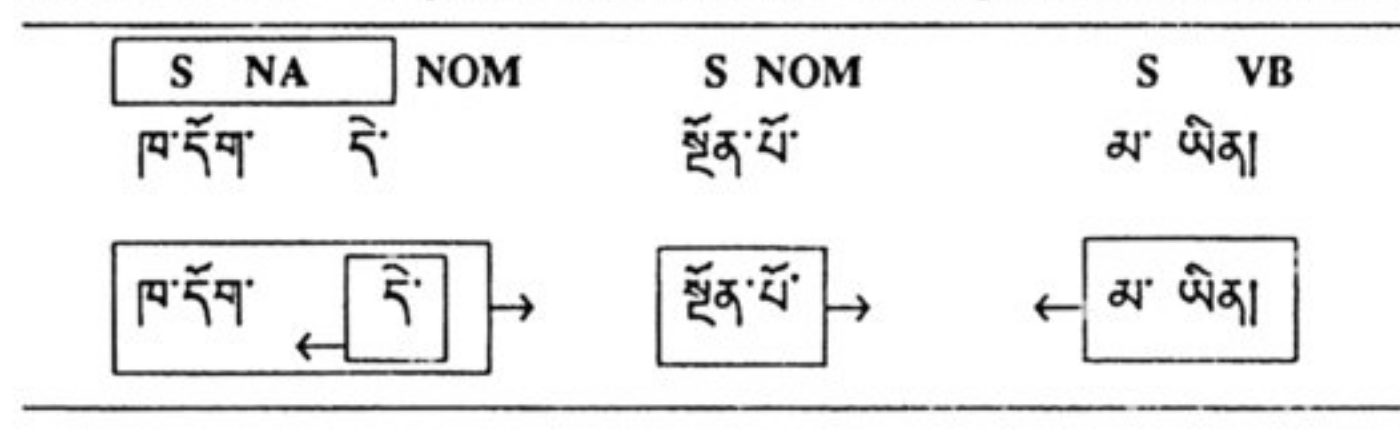

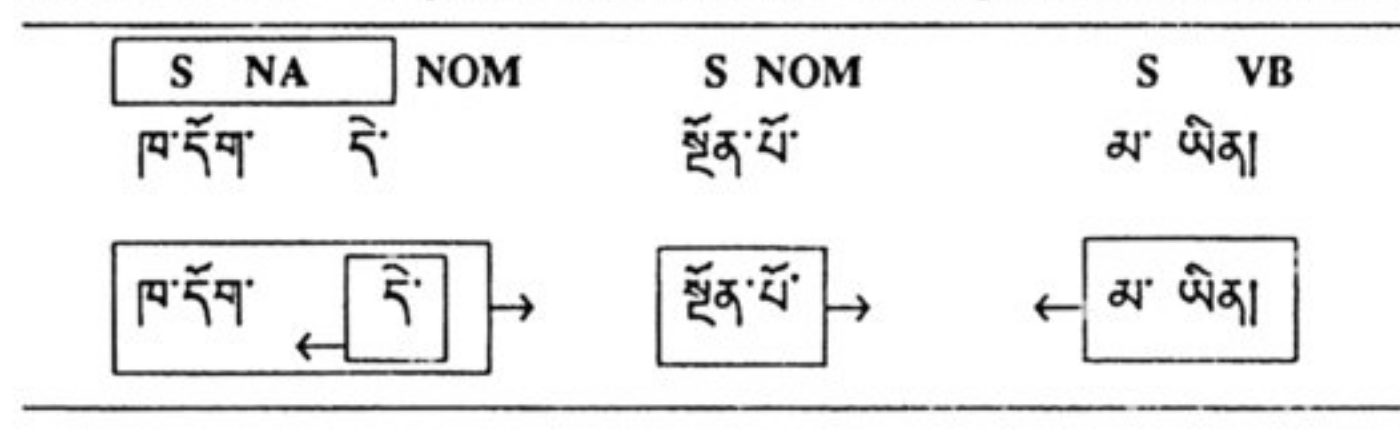

SUBJECT → COMPLEMENT → ← LINKING VERB

¶ Subject of a linking verb:

བུམ་པ་མི་རྟག་པ་ཡིན་

Pots are impermanent.

¶ Complement of a linking verb:

བུམ་པ་མི་རྟག་པ་ཡིན་

Pots are impermanent.

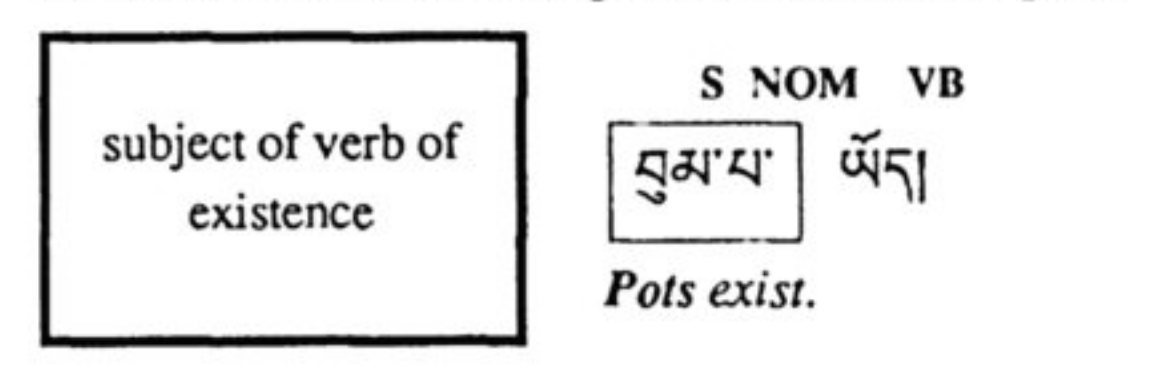

¶ Subject of a verb of existence:

The other nominative verbs also take nominative subjects. They are verbs of existence, verbs of living, verbs of dependence, and verbs expressing mental attitudes.

Verbs of existence are a very common usage of the nominative. That which exists (or does not exist) is in the nominative.

བུམ་པ་ཡོད་

Pots exist.

བུམ་པ་མེད་

Pots do not exist.

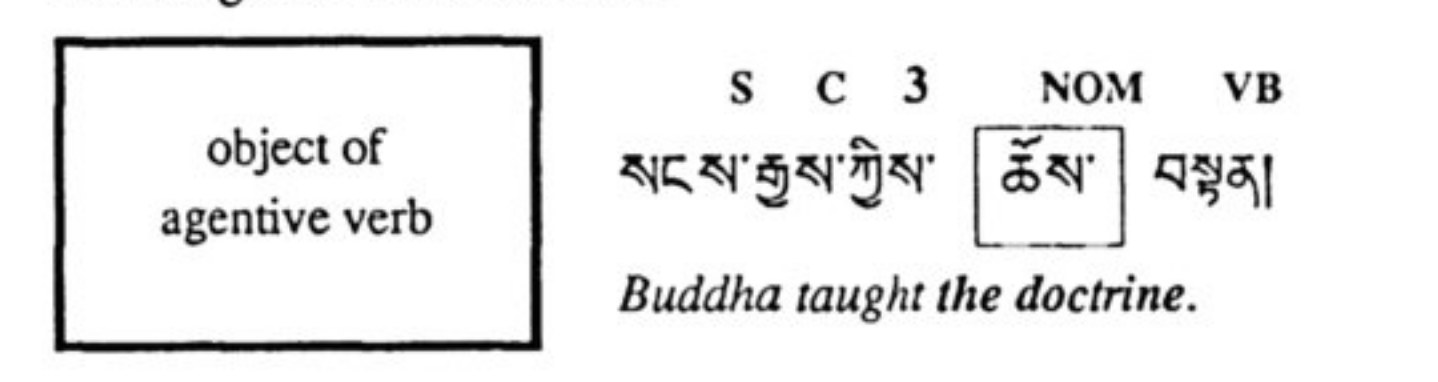

¶ Object of an agentive verb

Many of the agentive verbs take nominative objects. This is a common usage of the nominative. Notice that the agent (or subject, as Wilson calls it) of the agentive verb is marked with a third case particle (ཀྱིས་).

སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱིས་ཆོས་བསྟན།

Buddha taught the doctrine.

Recall that the case dots (C) following case marking particles may be replaced by the number of the case they indicate. Thus the 3 dot that follows the agentive particle (ཀྱིས་) above.

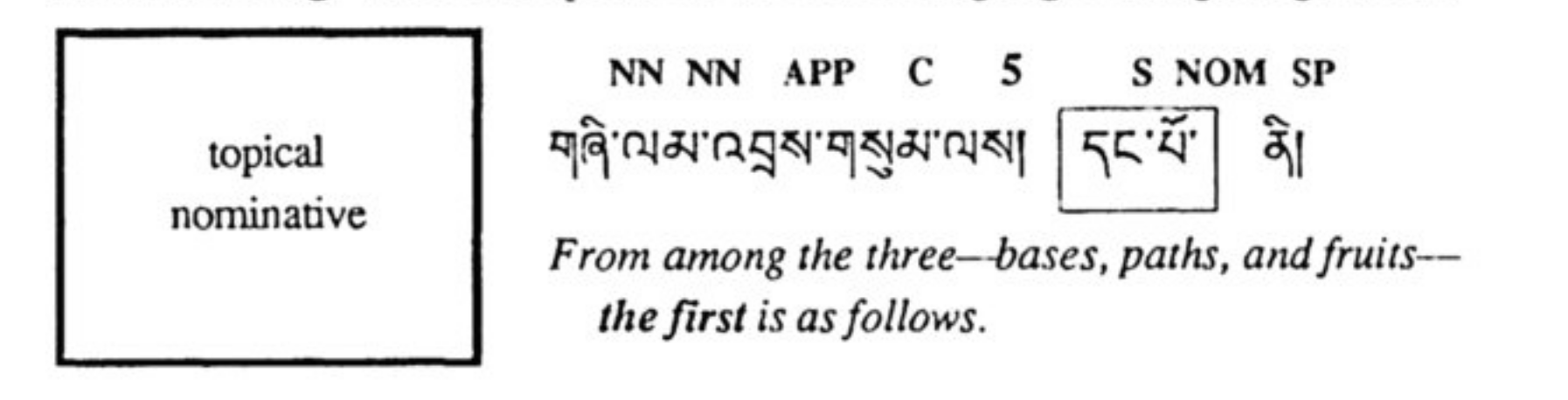

¶ Topical Nominative

A nominative standing alone at the beginning of a sentence may be unrelated grammatically to the sentence, serving as what in English might be a title or section heading. This corresponds to block language in English grammar and is called the topical nominative.

གཞི་ལམ་འབྲས་གསུམ་ལས། དང་པོ་ ནི།

From among the three – bases, path, and fruit – the first is as follows.

You have seen ལས་ elsewhere in its use as a noun meaning karma (action). Above it is a particle marking the fifth or originative case, specifically its use is to show separation.

¶ Connective Case Paradigms

There are five connective case marking particles: གི་, ཀྱི, གྱི, འི, ཡི

The sixth is unusual in that it does NOT relate nouns to verbs. Instead, it connects nouns, pronouns, and adjectives to other nouns, pronouns, and adjectives, or to postpositions.

The 6th case connective may indicate many sorts of connections. There are six major types of usage, within which there are (at least) 17 differentiable uses. Three of the more important are possession, type, and destination. These uses are covered in more detail starting on page 644 of Wilson in appedix five or in the corresponding page in the wiki.

¶ Possession connective

Using the 6th case to show possession is one of the more imp

བདག་ཅག་གི་སྟོན་པ་

our Teacher

Teacher is capitalized because it is an epithet of Buddha. བདག་ is the first person pronoun, “I”. ང་ is the more common first person pronoun. བདག་ is a more elegant form and is seen often in Classical Tibetan. Neither pronouns are honorific, as honorifics may only be used for others, never for oneself. Adding the pluralizing particle ཅག་ to བདག་ produces བདག་ཅག་ (we, us). Applying the connective particle གི་ then yields བདག་ཅག་གི་ (our).

བདག་ I (elegant)

ང་ I (colloquial)

བདག་ཅག་ we, us

བདག་ཅག་གི་ our

¶ Type connective

The type connective is closely related to the possessive connective. Type connectives answer the question “which?” or “whose?”

ཐག་ཆེན་གྱི་ཆོས་

doctrine of the Mahayana

¶ Destination connective

Other connectives imply relationships of origin, agency, destination, effect and cause, time, or place. The following example indicates a relationship of causality or, more literally, destination.

བྱང་ཆུབ་ཀྱི་ལམ་

path to awakening

What sort of path? A path that leads to བྱང་ཆུབ་ (awakening, bodhi). Not a path made of awakening, nor a path that belongs to awakening, but a path that leads there.

Although there is a general rule-of-thumb that one can translate a 6th case as of, and this does work sometimes, just about every English preposition will be appropriate in some instances and there will be many times when of will be entirely wrong.

¶

¶ Connective Case Markers - Lexical Dimension

The five connective case marking particles (གི་, ཀྱི, གྱི, འི, ཡི) have the same syntactic meaning. However, they are used according to the final syllable of the word they are marking.

- གི་ used after word whose final syllable ends in either ག་ or ང་

- ཀྱི་ used after a word whose final syllable ends in either ད་, བ་, ས་

- གྱི་ used after a word whose final syllable ends in either ན་, མ་, ར་, or ལ་

- འི་ merges with final syllables that end in འ་ or that have no final syllable

- ཡི་ is used after a word whose final syllable ends in འ་ or has no suffix letter

These rules simply have to be memorized. Fortunately, the agentive case marking particles follow exactly the same pattern.

¶ Verbs and Verb Syntax

There are many ways of classifying verbs. The highest level classification introduced in Wilson is:

- nominative verbs—whose subjects are in the first (nominative) case

- agentive verbs—whose subjects are in the third (agentive) case

- specialized verbs—whose subjects are mainly in the seventh (locative) case, but also one class in the fourth case (དགོས, need).

Another way of dividing verbs is into two basic types, with the second type, action verbs, having two subtypes.

- existential verbs—such as ཡིན་ and ཡོད་

- action verbs—such as བྱེད་ (do) and སྟོན་ (teach, show)

- transitive verbs—agent acts on something other than itself (The Buddha taught the doctrine, སངས་རྒས་ཀྱིས་ཆོས་བསྟན།)

- intransitive verbs—agent and object are the same (The wheel turns, འཁོར་ལོ་འཁོར།)

This system of verb classification is a descriptive system created by non-Tibetans, based largely on how English speakers thing about verbs and how verbs are categorized in Sanskrit. Tibetans classify verbs differently and primarily divide verbs into categories based on volition or effort (volitional vs non-volitional). See the wiki page on the indigenous Tibetan verb classification.

Although we speak of only three categories of verbs (nominative, agentive, and specialized), each category includes a number of different classes, within which there may be different types.

There are eight classes of verbs.

- Class I – IV are nominative verbs

- Class V – VI are agentive verbs

- Class VII – VIII are specialized verbs

There are eight classes of verbs and eight cases. This is a happy coincidence. There is no one-to-one mapping between verb types and cases.

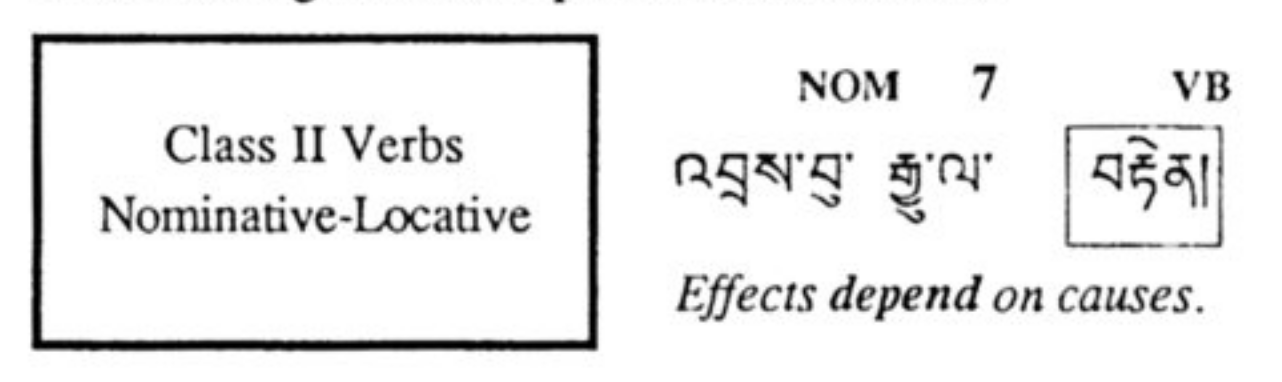

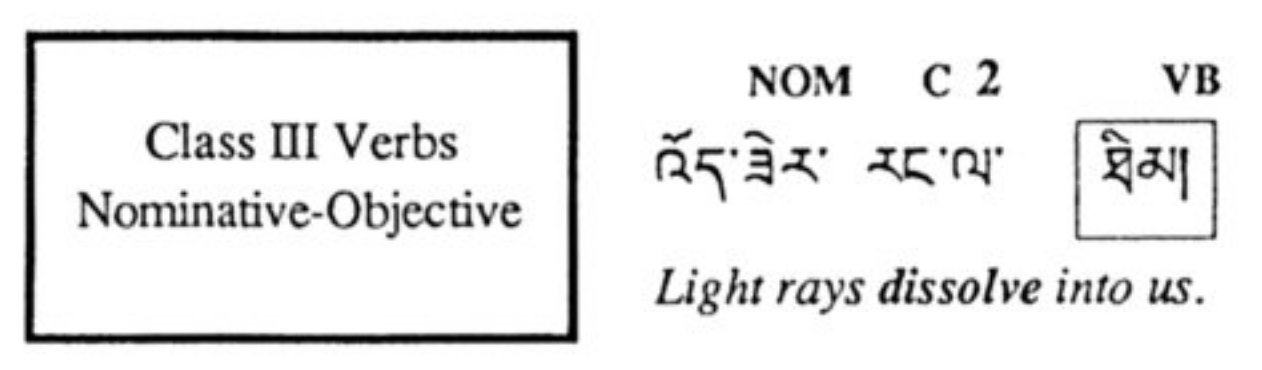

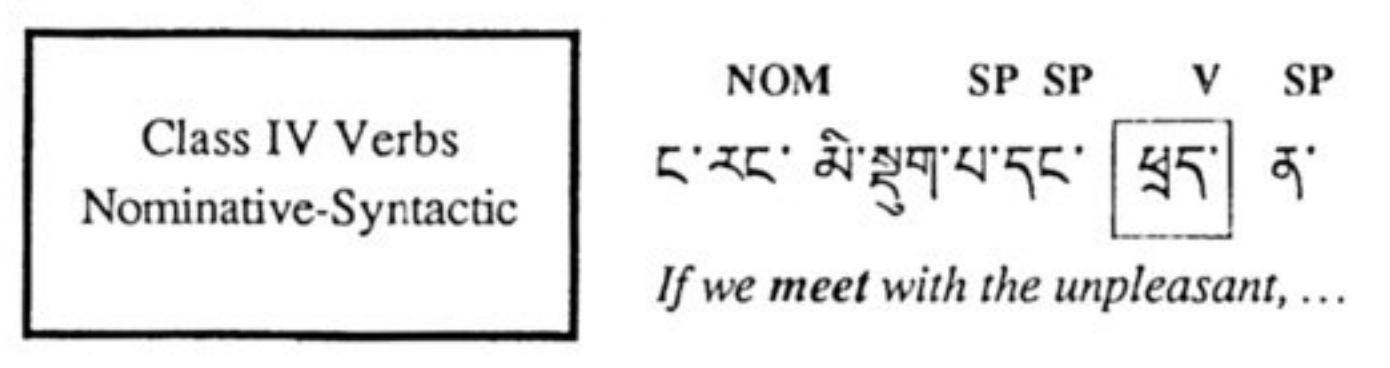

¶ Classes of Nominative Verbs

There are four classes of nominative verbs:

I nominative-nominative verbs: nominative subject and nominative complement

II nominative-locative verbs: nominative subject and locative (7th case) qualifier

III nominative-objective verbs: nominative subject and objective (2nd case) qualifier

IV nominative-syntactic verbs: nominative subject and qualifiers marked by syntactic particle

The fact that a nominative locative verb takes a qualifier in the locative case does not mean that it must have a particle, nor does it mean that all the qualifiers in sentences it ends must be in the locative case. The same is true for nominative-objective and nominative-syntactic verbs.

The case particles marking the subject of a given verb, its object, and its complement are fairly (although not invariably) predictable. However, there are many types of qualifiers possible in a given clause or sentence.

¶ Class I Nominative-Nominative

There is only one type of Class I verb: linking verbs, such as ཡིན་

Another linking verb, ལགས་, a synonym for ཡིན་ used to translate sutras

¶ Class I Nominative-Nominative

བུམ་པ་མི་རྟག་པ་ཡིན།

Pots are impermanent.

¶ Class II Nominative-Locative (7th)

There are a number of different types of Class II (nominative-locative) verbs:

- verbs of existence—such as ཡོད་, exist, for which the locative qualifier marking the place of existence is optional.

- verbs of living—or, verbs of continuing existence such as གནས་ (stay, live)—with the place where or the time during being marked by the locative.

- verbs of dependence—such as རྟེན་ (depend on), in which the thing or person upon which there is dependence is marked by the locative particle.

- attitude verbs—expressing mental attitudes taken about something (where the about translates a referential locative), such as འཇིགས་ (fear), ཆགས་ (is attached to), མཁས་ (is skilled in).

¶ Class II Nominative-Locative

འབྲས་བུ་རྒྱ་ལ་བརྟེན།

Effects depend on causes.

¶ Class III Nominative-Objective (2nd)

Class III verbs have objective (2nd) case qualifiers or objects. There are a number of different types of Class III verbs. All have nominative subjects and, sometimes optionally, objective case qualifiers.

Intransitive verbs are among these verbs. In the following example of a nominative-action verb, the light rays are both the agent and the object of the verb—they do the dissolving and are what dissolves.

¶ Class III Nominative-Objective:

འོད་ཟེར་རང་ལ་ཐིམ།

Light rays dissolve into us.

¶ Class IV Nominative-Syntactic

These verbs mainly show separation or conjunction.

ང་རང་མི་སྡུག་པ་དང་ཕྲད་ན་

If we meet with the unpleasant…

¶ Linking Verbs

The simplest Tibetan verb is ཡིན་, the most common copula (or linking verb). It is usually translated as is or are. A linking verb does one of two things:

- links a noun, pronoun, or adjective with another noun or pronoun

- links a noun, pronoun, or adjective with another adjective

Since nouns and pronouns can be grouped under the name substantive, another way of putting this is to say the following.

Linking verbs connect a substantive or an adjective with another substantive or adjective. Linking verbs have a subject and a complement. The subject HAS THE QUALITY OF BEING the complement.

Here are two examples of sentences ending in linking verbs. The first example refers to the Buddhist concept of personhood, which is far wider than that accepted by either scientists or philosophers in the Western tradition. In Buddhism, any sentient being is a person, and thus not only humans, but also animals, hungry ghosts, hell-beings, and gods are persons. Buddhas, likewise, are persons, but it is considered philosophically incorrect to say that a Buddha is a person, since included in the concept of Buddha is the cessation of all afflictions, and cessations (as we'll see in chapter 16) are permanent (that is, unchanging) phenomena, whereas persons are impermanent. Thus, the convention is to refer to Buddha the person as སངས་རྒྱས་འཕགས་པ་, or, as abbreviated here, སངས་འཕགས་.

སངས་འཕགས་གང་ཟག་ཡིན།

A Buddha superior is a person.

ཁ་དོག་གཟུགས་ཡིན།

Color[s] are form[s].

Diagrammed, the first sentence looks like:

In this sentence, སངས་འཕགས་ is the subject and གང་ཟག་ is the complement.

The structure of both of these sentences is:

SUBJECT → COMPLEMENT → ← VERB

ཡིན་ can be either is or are. Depending on context, it may also mean was or will be.

Tibetan is ambiguous as to number (singular or plural) and does not require indefinite or definite articles as English does. Classical Tibetan is also often ambiguous as to verb tense (past, present, or future). Many important verbs have the same spelling for some or all of the four verb forms: past, present, future, and imperative, thus context is used to determine which is implied. Colloquial or spoken Tibetan, in contrast, has a rich system of verb forms that makes verb tense and aspect very clear.

The word order in Tibetan sentences ending in linking verbs is not arbitrary. Take, for example, the following two sentences.

སངས་འཕགས་གང་ཟག་ཡིན།

BUDDHA SUPERIOR PERSON IS

A Buddha superior is a person.

གང་ཟག་སངས་འཕགས་ཡིན།

PERSON BUDDHA SUPERIOR IS

A person is a Buddha superior.

The first sentence is the correct sentence we saw above. The second has the subject and the complement switched, which makes a grammatically correct but doctrinally incorrect statement.

You could do the same thing with our other example linking verb sentence.

སེར་པོ་ཁ་དོག་ཡིན།

YELLOW COLOR IS

Yellow is [a] color.

ཁ་དོག་སེར་པོ་ཡིན།

COLOR YELLOW IS

Colors are yellow.

ཁ་དོག་སེར་པོ་ཡིན། could actually have a few other meanings. The meaning of a Tibetan sentence is dependent on its context far more than an English sentence typically is and frequently in Tibetan parts of a sentence may be omitted or implied. Consider, for example, if the sentence was an answer to a question, such as “What is that color?” The sentence could then be interpreted as an appositive construction in which the subject was unstated, [that color] is the color yellow.

[ཁ་དོག་དེ་]ཁ་དོག་སེར་པོ་ཡིན།

[that color] is the color yellow.

Because Tibetan is ambiguous about number (singular or plural), ཁ་དོག་སེར་པོ་ཡིན། could also mean:

Colors are yellow.

A color is yellow.

Color is yellow.

The color is yellow.

The colors are yellow.

Finally, ཡིན་ sentence constructions are so common that the verb itself is frequently omitted. Take, for example, the following famous two sentences from the Heart Sutra.

།གཟུགས་སྟོང་པའོ། །སྟོང་པ་ཉིད་ཀྱང་གཟུགས་སོ།

Form is empty. Emptiness is form.

Both of the sentences end with terminating particles (འོ and སོ). They have no lexical meaning and in this case serve to disambiguate the grammar and act as rhetorical flourishes, emphasizing the points being made. The second sentence has a ཀྱང་, which is untranslated here. ཀྱང་ can mean just about any type of interjection, conjunction, or disjunction: or, and, but, even, also, however, etc.. With these particles removed, and with the implied ཡིན་'s added back in, you get the following.

།གཟུགས་སྟོང་པ་ཡིན། །སྟོང་པ་ཉིད་གཟུགས་ཡིན།

FORM EMPTY IS EMPTINESS FORM IS

Notice that སྟོང་པ་ (empty) becomes སྟོང་པ་ཉིད་ (emptiness) in the second sentence. Form is not emptiness. Form is empty. Yet, emptiness is form.

It's worth thinking about these two statements. That form is empty is a pretty straightforward Tibetan Buddhist statement. Speaking from the perspective of Prāsaṅgika Madhyamaka, all things lack inherent existence, including form. Therefore, form is clearly empty (that is, lacking inherent existence). However, in what way is emptiness form? Does emptiness have the quality of being form? This is less clear.

Emptiness is not form in a strict copulative sense. Emptiness does not have the quality of being form in the way that form has the quality of being empty. However, if we take this statement metaphorically, we can understand it to be saying that it is only because form lacks inherent existence that form can exist and function. Without emptiness there could be no form. Thus emptiness is form in the metaphoric sense that without emptiness form could not exist. Also, we can understand that a form and it's emptiness are inevitably tied together in one entity – being created, abiding, and ceasing together – but emptiness is not form in the sense that emptiness has the quality of being form because the two are mutually exclusive. There is nothing that is both form and its emptiness.

སྣང་བ་རྟེན་འབྲེལ་བསླུ་བ་མེད་པ་དང་།

སྟོང་པ་ཁས་ལེན་བྲལ་བའི་གོ་བ་གཉིས།

ཇི་སྲིད་སོ་སོར་སྣང་བ་དེ་སྲིད་དུ།

ད་དུང་ཐུབ་པའི་དགོངས་པ་རྟོགས་པ་མེད།

As long as the two, realization of appearances – the infallibility of dependent-arising –

And realization of emptiness – the non-assertion [of inherent existence],

Seem to be separate, there is still no realization

Of the thought of Shakyamuni Buddha.

– From Tsong-kha-pa's Three Principal Aspects of the Path

This last point is a subtle and important point in the Gelug presentation of emptiness and the two truths. Every phenomena is empty of inherent existence. Take a table, for instance. The phenomena of a table exists conventionally, merely imputed to its parts. Ultimately, however, the table is empty, and although its emptiness abides with the table and its parts as one entity, there is nothing that is both the table and its emptiness. A table and its emptiness necessarily exist together, yet there is nothing that is both of them.

This is all speaking from the standpoint of Prāsaṅgika Madhyamaka. It is possible to interpret this famous statement from a Mind Only perspective as well, interpreting it with respect to the three natures and the three non-natures. If this interests you, read Chapter 5 of Lopez's The Heart Sutra Explained.

For more on the Gelug (and Tsong-kha-pa's) presentation of the two truths, see Guy Newland's excellent book The Two Truths: In the Madhyamika Philosophy of the Gelukba Order of Tibetan Buddhism. There's also an interesting book that compares some doctrinal differences in understanding of the two truths by Sonam Thakchoe called The Two Truths Debate: Tsongkhapa and Gorampa on the Middle Way.

¶ Negative Linking Verbs

To negate ཡིན་ one simply adds a མ་ → མ་ཡིན་. This is translated as is not or are not.

ཁ་དོག་དེ་ སྔོན་པོ་ མ་ཡིན།

THAT COLOR BLUE IS NOT

That color is not blue.

The མ་ means nothing by itself. མ་ཡིན་ should be considered a single word.

མ་ཡིན་ can also be shortened to མིན་.

ཁ་དོག་དེ་ སྔོན་པོ་ མིན།

That color is not blue.

Continuing the theme of the Heart Sutra, take a look at the next two lines from the sutra. They are a great example of negative linking verbs. Also note that while ཡིན་ is often omitted, མ་ཡིན་ cannot be omitted.

།གཟུགས་ལས་སྟོང་པ་ཉིད་གཞན་མ་ཡིན་ནོ། །སྟོང་པ་ཉིད་ལས་ཀྱང་གཟུགས་གཞན་མ་ཡིན་ནོ།

།གཟུགས་ལས་ སྟོང་པ་ཉིད་ གཞན་ མ་ཡིན་ ནོ། །སྟོང་པ་ཉིད་ལས་ ཀྱང་ གཟུགས་ གཞན་ མ་ཡིན་ ནོ།

Emptiness is not other than form. Form is not other than emptiness

གཟུགས་ form

ལས་ translated as “than” here, showing comparison or separation

སྟོང་པ་ཉིད་ emptiness [empty + restrictive suffix syllable -ness]

གཞན་ other

མ་ཡིན་ is not

ནོ་ terminating particle

The grammar of these two sentences is exactly the same. Here is one broken down.

།གཟུགས་ལས་སྟོང་པ་ཉིད་གཞན་མ་ཡིན་ནོ།

Emptiness is not other than form.

FORM THAN EMPTINESS OTHER NOT IS

Parsing this sentence may seem a little complicated. If we take out the གཟུགས་ལས་ for a moment, it may make it easier.

སྟོང་པ་ཉིད་ གཞན་ མ་ཡིན།

EMPTINESS OTHER NOT IS

Emptiness is not other.

Emptiness is not other. Not other than what? གཟུགས་ལས་ – not other than form. This is confusing because the word order is very different than English and other (གཞན་) is separated from than form (གཟུགས་ལས་). So it reads in Tenglish more like Than form, emptiness is not other.

Here's another example with a compound subject.

ཁ་དོག་དང་སྔོན་པོ་འགལ་བ་མ་ཡིན།

Color and blue are not mutually exclusive.

འགལ་བ་ means mutually exclusive – that is to say, there is no phenomena that is both things in consideration. In the example above, for color and blue to be mutually exclusive, there would have to be no phenomenon that is both blue and a color. This is not true because the color blue is both blue and a color. However, color and a blue car are mutually exclusive. A blue car is a car, and there is nothing that is both a car and a color. The color of a blue car, in contrast, is a color and is blue, and thus is not mutually exclusive with color or blue.

¶ Linking Verbs Other Than ཡིན་

ཡིན་ and its negation མིན་ (or མ་ཡིན་) are the most frequently used linking verbs in all periods of Tibetan literature. In the modern colloquial language ཡིན་ and མིན་ are used only for the first person declarative (I am, I am not) and the second person interrogative (Are you? Are you not?). In the classical written language being analyzed here, ཡིན་ and མིན་ are used without regard to person or tense (past, present, or future).

རེད་ and མ་རེད་ are linking verbs that are not used much in classical Tibetan but are everyday linking verbs in colloquial Tibetan, as such they may appear occasionally in more contemporary writings. Remember that Tibetans do not think of classical Tibetan and colloquial Tibetan as different languages, but more as different registers of the same language, much in the way that Tibetan has normal and honorary (or humilific) registers. That is not to say, however, that the average Tibetan can read and understand a classical Tibetan treatise, which may contain complexities of grammar and vocabulary well beyond what is typical for an average Tibetan.

There are also other linking verbs. ལགས་ and མ་ལགས་ are commonly used when translating sutras from Sanskrit. The following is an example from the Diamond Cutter Sutra:

བཅོམ་ལྡན་འདས་ ངོ་མཚར་ ལགས་སོ།

O Transcendent Victor, [it] is amazing.

བཅོམ་ལྡན་འདས་ Transcendent Victor, Bhagavan, [conqueror-possessing-passed beyond], Supramundane Victor, Blessed One, Buddha

ངོ་མཚར་ amazing

བཅོམ་ལྡན་འདས་ is one of the many names for a Buddha. It is translated above as Transcendent Victor. It is the translation of the Sanskrit term Bhagavan. This is sometimes translated as Blessed One, but this is incorrect. A Bhagavan has not been blessed by any higher power in the way that Blessed One implies in English – of course, to varying degrees in different traditions of Buddhism, a practitioner may ask for blessings from realized beings and may even rely on help from realized beings to achieve enlightenment, but this is not the sense being communicated here by Blessed One, where in English blessing generally takes on the Judeo-Christian connotations of being blessed by a creator god.

There are two traditional Buddhist etymologies for the Sanskrit term Bhagavan. One suggests a translation as Fortunate One (See Lopez, Heart Sutra Explained, and Chandra, Tibetan-Sanskrit Dictionary, p. 2321, where the Tibetan ལེགས་ལྡན་ or fortunate translates the Sanskrit bhagavan), which helps explain where Blessed One comes from. However, the etymology followed by Tibetan translators when they translated Sanskrit texts a thousand years ago resulted in the term བཅོམ་ལྡན་འདས་, which has three parts:

- བཅོམ་, victor or conqueror

- ལྡན་, possessing

- འདས་, transcend or beyond

A བཅོམ་ལྡན་འདས་ is someone, a Buddha, who has conquered, who possesses, and who has transcended.

- A Buddha has conquered the afflictions, chiefly ignorance, hatred, and desire.

- She possesses the “six goodnesses” (ལེགས་པ་དྲུག་དང་ལྡན་པ་) or positive qualities: excellent power, excellent form, excellent marks and signs, excellent renown, excellent pristine wisdom, and excellent joyous effort.

- She has transcended, or has gone beyond, both cyclic existence and nirvana.

An alternative etymology says that བཅོམ་ means that a Buddha has destroyed the four māras, sometimes translated as demons, which create obstacles on the path.The four māras (catvāri māra, བདུད་བཞི་) are:

- māra of the aggregates (skandhamāra, ཕུང་པོའི་བདུད་) – symbolizes our clinging to forms, perceptions, and mental states are real

- māra of the afflictions (kleśamāra, ཉོན་མོངས་ཀྱི་བདུད་) – symbolize our addition to habitual patterns of negative emotion

- māra of the Lord of Death (mṛtyumāra, འཆི་བདག་གི་བདུད་) – symbolizes both death itself, which cuts short our precious human birth, and also our fear of change, impermanent, and death

- the māra of the son of gods (devaputramāra, ལྷའི་བུའི་བདུད་) – symbolizes our craving for pleasure, convenience, and "peace"

Rigpa Wiki has a good entry on the four maras. Also StudyBuddhism and tubtenchodron.org.

Lopez (Heart Sutra, pp. 28-29) reports a contemporary explanation of the term བཅོམ་ལྡན་འདས་: “An oral commentary states that བཅོམ་ means the destruction of the two obstructions and indicates the Buddha's marvelous abandonment; ལྡན་ means that the Buddha is endowed with the Wisdom Truth Body ( jñānadharmakāya, ཡེ་ཤེས་ཆོས་སྐུ།), the omniscient consciousness, and indicates the Buddha's marvelous realization; and འདས་ means that the Buddha has passed beyond the extremes of mundane existence and solitary peace."

འདས་ is not a direct translation of the Sanskrit term but was added in the Tibetan translation to differentiate the Buddhist Bhagavan from other conquerors because the Buddhist Bhagavan has transcended the extremes of existence (in samsara) and peace (mere nirvana).

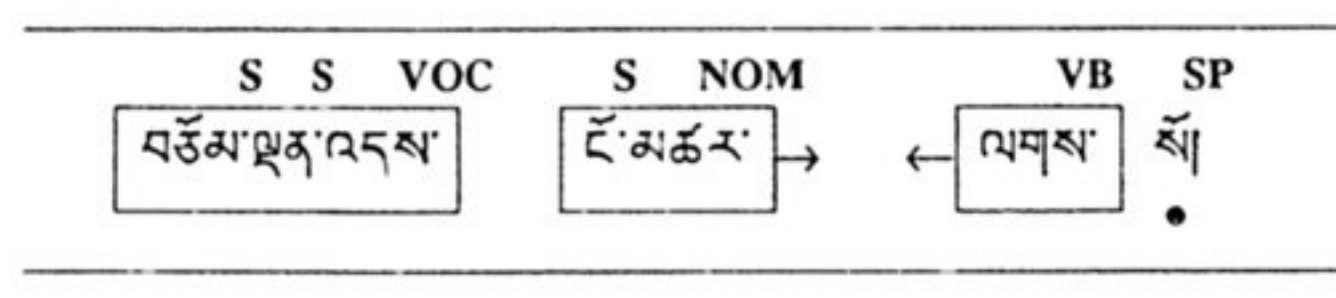

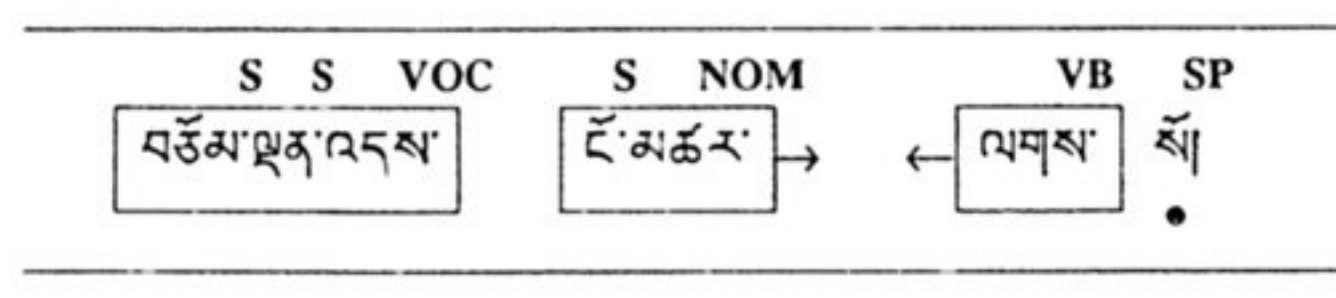

¶ Vocative Case

You may be wondering why the sentence did not say The Bhagavan is amazing. Look at the sentence again.

བཅོམ་ལྡན་འདས་ ངོ་མཚར་ ལགས་སོ།

O Transcendent Victor, [it] is amazing.

VOCATIVE, [OMITTED SUBJECT →] COMPLEMENT → ← VERB

It would seem like བཅོམ་ལྡན་འདས་ would be the subject, ངོ་མཚར་ the complement, and ལགས་ a simple linking verb. Why bring in the unstated it? How do we know?

This sentence is an example of the vocative. The vocative is defined as “relating to or denoting a case of nouns, pronouns, and adjectives in Latin and other languages, used in addressing or invoking a person or thing.” It is translated as Oh, god! or Oh, Bhagavan! – in the sense of an emotional direct address.

The vocative is really quite simple. There are no case markings for the vocative, although sometimes interjection such as ཀྱེ་ or ཀྭ་ཡེ་ appear. You just have to recognize it to avoid confusion. The vocative is very common in translations of sutras and tantras, which are framed as conversations with Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. It's use is less common in Tibetan writings on philosophy and meditation.

Since this is an excerpt from the Diamond Cutter Sutra, we know from context that བཅོམ་ལྡན་འདས་ is not the subject but is, in fact, the person being addressed. That leaves the following sentence:

ངོ་མཚར་ལགས་སོ།

[something] is amazing.

Here we fill in the pronoun it. Notice that we know that ངོ་མཚར་ must be the complement of the linking verb. When one of the terms of a linking verb is unstated, it is always the subject, never the complement.

Notice that in the diagram of the sentence (repeated below), there is no arrow attached to the vocative. Vocatives are neither subjects, objects, nor qualifiers of verbs, nor do they modify other words, as do adjectives, adverbs, and phrases in the connective case.

Vocatives can occur in other positions as well, as long as they precede the verb. They do not occur frequently in expository philosophical and meditative literature; however, they do occur in poetic treatments of philosophy and meditation (particularly in verse, which is much more common in Tibetan than in English when writing about these subjects).

¶ Lexical Particles

There are 13 frequently seen prefix particles that are used to translate Sanskrit prefixes. In the Tibetan translations of Sanskrit terms listed below, it should be noted that frequently many Sanskrit words are translated by one Tibetan “equivalent.”

It is important to be able to recognize these prefix particles. Understanding their meaning is also helpful; although, it is not always straight forward to predict the meaning of the word from the meaning of the prefix.

ནམ་པར་ vi-

ནམ་པར་གྲོལ་བ་ : vimokṣa, vimukta – liberation and liberated

ནམ་པར་རྟོག་པ་ : vikalpa, vitarka – conceptuality or thought

ནམ་པར་བཞག་པ་ : vyavasthāpana – presentation

May be thought of as indicating 1) separation or distinction, 2) emphasizing or intensifying. A rough translation would be separately … or very …

ཀུན་དུ་, ཀུན་ནས་ sam-

thoroughly …, extensively …

ཀུན་ཏུ་འབྱུང་བ་ : samudaya – origin

ཀུན་ཏུ་བཟང་པོ་ : Samantabhadra

ཀུན་ནས་ཉོན་མོངས་པ་ : saṃkliṣṭa – thoroughly afflicted

མངོན་པར་ abhi-

exceptionally …, manifestly …

མངོན་པར་ཤེས་པ་ : abhijñā – clairvoyance

མངོན་པར་རྟོགས་པ་ : abhisamaya – realization

ངེས་པར་ nir- (niḥ-, niś-)

definitely …

ངེས་པར་འབྱུང་བ་ : niḥsaraṇa – renunciation, definite emergence

ངེས་པར་ཤེས་པ་ : niścaya – ascertainment

ཡོངས་སུ་ pari-

completely …, thoroughly …

ཡོངས་སུ་གྲུབ་པ་ : pariniṣpanna – thoroughly established (and by extension, completely existent)

ཡོངས་སུ་དག་པ་ : pariśuddhi – thoroughly pure, thoroughly purified

རྗེས་སུ་ anu-

after or along with

རྗེས་སུ་དཔག་པ་ : anumāna – inference

རྗེས་སུ་མཐུན་པ་ : anulomika, anukūla – concordant, similitude

ཉེ་བར་ upa-

suggests nearness (both in terms of location and approximation), but is also used as an intensifier like vi-

ཉེ་བར་ལེན་པ་ : upādāna – appropriation

ཉེ་བར་ཞི་བ་ : vyupaśama – pacified or pacification

སོ་སོར་ prati-

separately …, individually …

སོ་སོར་ཐར་པ་ : pratimokṣa – individual liberation

རབ་ཏུ་ pra-

thoroughly …, exceptionally …

རབ་ཏུ་དགའ་བ་ : pramudita – joyous

རབ་ཏུ་བྱུང་བ་ : pravrajita – going forth (becoming a monk)

The remaining three are not used as frequently to translate Sanskrit prefixes. Sometimes they translate adjectives or are without a Sanskrit equivalent. ལེགས་པ་ (without the ར་) means good. ཡང་དག་པ་ (without the ར་) means correct. ཤིན་ཏུ་ is sometimes used as an intensifying adverb (very).

ཡང་དག་པར་ samyak-

ཤིན་ཏུ་ pra-, su-

ཡང་དག་པ་ su-

¶ Abbreviated Nouns and Adjectives

It’s common for nouns and adjectives to be abbreviated by dropping syllables. In words with པར་ and པ་, those syllables are often dropped, as are other middle syllables, such as སུ་ or ཏུ་. The pattern here is that in longer four-syllable words, the less important second and fouth syllables are often dropped.

རྣམ་པར་བཞག་པ་ → རྣམ་བཞག་

རྣམ་པར་ཤེས་པ་ → རྣམ་ཤེས་

ངེས་པར་འབྱུང་བ་ → ངེས་འབྱུང་

ལེགས་པར་བཤེད་པ་ → ལེགས་བཤེད་

ཡོངས་སུ་གྲུབ་པ་ → ཡོངས་གྲུབ་

རབ་ཏུ་བྱུང་བ་ → རབ་བྱུང་

ངེས་འབྱུང་ is generally pronouns ngen jung, with the འ nasalizing the previous syllable, creating an “n” sound – ngen jung instead of nge jung.

The syllables ཉེ་པར་ are abbreviated ཉེར་.

ཉེ་བར་ལེན་པ་ → ཉེར་ལེན་

The syllables སོ་སོར་ are abbreviated སོར་ or སོ་

སོ་སོར་རྟོགས་པ་ → ཉེར་ལེན་

སོ་སོར་ཐར་པ་ becomes སོ་ཐར་